On July 2nd, 2024, I found myself in a brawl with thousands of New York families, influencers, and out-of-town visitors. We flocked to Yelp, desperately scrolling past a never-ending slew of grayed-out dates and “no availability” notices. As I was about to accept defeat, I found myself squinting at the screen in disbelief – my fingers were hovering over a highlighted slot! I clicked, refreshed, and emerged as the victor.

“You’re booked at Din Tai Fung NYC.”

My victory was no easy feat– the world renowned Taiwanese dumpling house had opened its reservation books at 1 p.m., and by 8 p.m., every available table had been reserved.

Two years ago, executives of Paramount Group, a real estate investment trust, announced that Din Tai Fung signed the lease for a sprawling 26,400 square feet retail space on Broadway, designed to accommodate just over 450 guests. Although Din Tai Fung consisted of over 182 outposts across major cities such as Hong Kong, Toronto, Washington, and California, they had yet to open a location in New York City – especially one that would operate at this scale.

In February of 2024, the media buzzed with anticipation – rumors had it that 200 new hires were participating in a rigorous dumpling training program in the underground space. Just a month later, Din Tai Fung reappeared in headlines when publicists excitedly announced that the restaurant was set to open in the Spring. However, as May approached, expectant New Yorkers were disappointed to find that “Steaming Soon!” signs remained nailed to Din Tai Fung’s boarded windows. Eater NY teased the three-year drag, referring to Din Tai Fung as the “most anticipated New York City restaurant of 2024, 2023, and 2022.”

The anticipation finally ended for a small group of fortunate diners on July 11th, 2024. As Din Tai Fung New York City’s first guests, they were privy to a limited menu during the restaurant’s soft opening. Others would have to wait another week until the chain’s official grand opening, which had been declared as the “restaurant event of the summer”. On July 18th, 2024, undeterred by the light rain and brutal heatwave, Din Tai Fung devotees crowded between West 50th and 51st Street in Manhattan, watching with bated breaths as third-generation owners Albert and Aaron Yang sliced the red-ribbon.

Albert Yang had addressed the crowd, “Our company’s purpose is to share our food and culture…what better place to do it than New York?”

The Din Tai Fung NYC Experience

Since the ribbon-cutting ceremony, Din Tai Fung’s corporate chef James Fu has estimated that between 3,000 to 5,000 people walk through its doors every day.

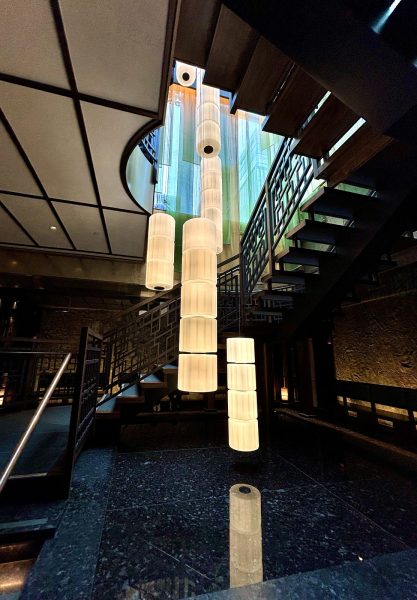

At the entrance, guests pass through a vibrant glass cube adorned with a waterfall of blue and green mesh curtains. Then, they begin their descent down a winding staircase, where an upwards glance reveals a grand skylight and hanging light fixture.

During the design process, Din Tai Fung enlisted the creative minds of Rockwell Group, a New York based architecture firm known for its dramatic Broadway show sets and video art installations. “We felt it made sense for the design of the restaurant to reflect the grandeur of its size and location in the heart of the Theater District and Times Square,” said Aaron Yang. The layout was inspired by the bamboo forests, central pavilions, and courtyards of a traditional Chinese garden. According to the Rockwell Group, “each space in the restaurant is almost like its own unique stage set, using dramatic forms, vibrant colors, and moody lighting.”

At the center of the space is a cocktail bar, designed to serve walk-in guests. Opposite the bar, diners are crowded together, their palms and noses pressed against a glass wall. Their eyes follow as thirty white-coated chefs knead dough and scoop filling, fingers flexing as they pinch the dough with masterful precision. This dioramic spectacle is Din Tai Fung’s open-kitchen, which is the centerpiece in all of its locations and has thus become the chain’s most iconic feature.

The chefs craft identical dumplings, each with 18 crimped pleats and a consistent weight of 21 grams– 16 grams of filling, 5 grams of dough. “The 18 folds not only look beautiful, but they also ensure the filling and soup have enough room to expand during the cooking process. This precision creates a harmonious balance between the delicate wrapper, savory filling, and rich broth,” Aaron Yang explained in a Michelin Guide interview. This meticulous standard of dumpling creation is referred to as the “Golden Ratio,” and by the end of the workday, ten thousand Golden Ratio dumplings will have been produced.

On either side of the open kitchen and central bar are the dining rooms. Each dining room mirrors the other, but is defined by a different color palette: one is lit by hues of green emerald, the other red jade. My table was situated in the red dining room, under the dim glow of a lantern-inspired light fixture. To my surprise, I was led to the table after a wait of ten minutes – just enough time to take a picture with Din Tai Fung’s dumpling mascot, admire the waiting room (reminiscent of a hotel lobby), and observe the practiced coordination between greeters and waiters. The short wait may have confirmed speculations of Din Tai Fung’s deliberate underbooking – a business strategy meant to generate long-term demand. Nevertheless, I was promptly tucked into a booth, and then given a strip of paper and a stubby pencil. The paper menu boasted a list of 40 dishes, their spice level, and a small space to scrawl your desired quantity (if any) of each.

The Sea Salt Cream Iced Tea was my first order to arrive. I reveled in the delicate floral notes of jasmine green tea, perfectly complemented by the subtly savory creaminess of the hand-whipped sea salt foam. Meanwhile, my meal began to unfold with a refreshing cucumber salad.

It was perfect in its simplicity – crisp, chilled cucumber slices lightly salted and drizzled with aromatic sesame oil and a touch of chili oil for a subtle kick. My next taste was Noodles with Sesame Sauce. The egg noodles were chewy, coated in a rich sauce made from sesame paste, chili oil, and soy sauce. Topped with crushed peanuts and fresh scallions, each bite delivered a balance of spice and nuttiness that kept me craving for more.

Around me, waiters expertly balanced towering stacks of bamboo steamer trays, gradually shedding layers from each stack, table by table. My waitress lowered three steaming trays onto my table: crab and Kurobuta pork xiao long bao (soup dumpling), chicken xiao long bao, and the kimchi Kurobuta pork dumpling.

Before I had dug into the dumplings, my waitress had recited the four-step process to enjoying the xiao long bao:

- Put one part soy sauce and three parts vinegar into the saucer.

- Take the soup dumpling and dip it into the sauce.

- Put the dumpling into your spoon and pierce a hole into the top of the dumpling’s skin to release the soup.

- Finally, enjoy.

My favorite dumpling was the crab and Kurobuta pork soup dumpling. The skin was translucent, thin, and stretchy, encasing a hearty blend of sweet crabmeat and tender Kurobuta pork. A first bite reveals a warm, silky broth that explodes with rich umami flavor.

(Katelyn Chiao)

I have visited many well-established dumpling empires across New York City (Joe’s Shanghai and Nan Xiang Xiao Long Bao), but this was my first time experiencing a choreographed delivery of dumplings.

The waitress qualified that I could eat the dumplings in any way I pleased, adding that it was required for waiters to run through the speech. This was likely one of the many standardized procedures that waiters had committed to memory by the end of their 3-week training period.

Although seemingly mechanical, Din Tai Fung iterates that its service procedures are rooted in the chain’s core values of quality, consistency, and warm hospitality. These are ideas that have guided Din Tai Fung since its humble beginnings as a small family-run business on the cramped alley-streets of Taiwan.

Yovan Li ‘25 said, “I have eaten at Din Tai Fung restaurants in both Seattle and New York, and the quality of their food and service is almost identical.” Others have agreed. In fact, it is commonly joked that the only difference between Din Tai Fung locations across the world are their time zones and the farms supplying their meat.

“As an independently owned family business…consistency starts with a strong commitment to our grandfather’s values and legacy,” said Aaron Yang.

Bing Yi-Yang and the Beginnings of Din Tai Fung

Aaron and Albert Yang’s grandfather, Bing-Yi Yang, was born in China’s Shanxi province. After Japan’s defeat in World War II, his hometown was swept into the chaos of China’s civil war. In the 1940s, Yang joined nearly 2 million other refugees who fled the mainland for Taiwan, seeking stability and the promise of economic opportunity. According to company legend, 21-year-old Yang escaped with nothing but $20 in his pocket.

In Taiwan, Yang met his wife, Lai Peng Mei. To support their growing family, Yang took on multiple jobs as a delivery man before the couple opened a small cooking oil business called “Din Mei Oils” in 1958. However, due to the rise of canned oil, the shop soon faced declining demand. Desperate to keep the business afloat and provide for their five children, Yang and Lai took a family friend’s advice to transform their storefront into a noodle and soup dumpling boutique. Yang was particularly skilled in this craft, having learned dough-making techniques as a child in his native Shanxi province.

On a Taiwanese television show, Yang recalled that “The first store was a small, earthen house with red tiles, we worked and slept there… I was on call all the time. I did not take one step away.”

By 1972, the couple had transformed the small eatery into a blossoming business, and were opening their first restaurant location in Taiwan’s capital city, Taipei. They named the restaurant Din Tai Fung, “din” referring to a cooking vessel and “tai fung” combining the Chinese characters of “peace” and “abundance.”

Din Tai Fung was built near a government settlement for Chinese military refugees and their families. Thus, many of the restaurant’s first customers were native Chinese soldiers who craved the familiar tastes of home. A former soldier, who had fled to Taiwan during the Chinese troop exodus in 1949, shared with Yang that Din Tai Fung’s soup dumplings brought back memories of the home in China to which he could never return.

As the mom-and-pop shop captured the hearts of locals, it would soon reach the ears of foreign diners. In 1993, Ken Hom, an American chef and journalist, visited Din Tai Fung under the recommendation of a Taiwanese chef. “I couldn’t believe how great the food was. It was just fantastic in its simplicity and taste,” Hom said. Following his visit, Hom penned a fervent 300-word review for The New York Times’ list of 10 Top Notch Tables, which catapulted the establishment into international spotlight. “I wrote about Din Tai Fung because I thought it was a great discovery for the world.” Hom recalled. The world agreed. His review attracted such large crowds that Din Tai Fung ceased serving dumplings on weekdays for several years. Yang later commemorated the article by having it engraved on bronze plaques displayed at various Din Tai Fung locations.

Globalization

As Din Tai Fung’s Taipei location drew large numbers of foreign travelers, the restaurant began to embrace the prospect of expansion.

Globalization commenced when Ji Hua Yang (Warren), the eldest son of Yang and Lai, became Din Tai Fung’s CEO in 1995. Warren obtained support from the executives of a department store in Tokyo, who were willing to finance the opening of a Din Tai Fung outlet and send selected chefs to Taiwan for training. In 1996, the first overseas restaurant opened in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, Japan. Four years later, Warren’s younger brother, Frank Yang, established Din Tai Fung’s first U.S. location in a strip mall northeast of Los Angeles.

Hom, who followed Din Tai Fung’s growth in the decades after his first visit, has now dined in locations across the globe. He has developed a practice of eating the soup dumplings slowly, leaving a few dumplings untouched in the bamboo basket to assess whether the delicate skin would sustain the soup and meat filling. It always did. Hom insists that the dumpling’s consistency is a standard set by Yang’s drive for precision. “I could feel his passion to not only get it right, but — it’s almost pride — to make it absolutely perfect,” he said.

At Din Tai Fung NYC, it was this detail and precision that left me in awe. From the tablet-wielding greeters and fishbowl kitchen to the mathematically-spaced tables and cycles of runners zig-zagging between them, Din Tai Fung is a dizzying, disorienting spectacle orchestrated with the friendly yet rigid hospitality of a mass-entertainment experience.

Quality soup dumplings and expansive menus can be found at countless long-standing eateries across the five boroughs. But if you’re an artist, an architect, or simply a diner seeking a theatrical adventure of grandeur and perfection, Din Tai Fung NYC offers an experience that transcends the meal itself – one that lingers long after the last bite.

Quality soup dumplings and expansive menus can be found at countless long-standing eateries across the five boroughs. But if you’re an artist, an architect, or simply a diner seeking a theatrical adventure of grandeur and perfection, Din Tai Fung NYC offers an experience that transcends the meal itself – one that lingers long after the last bite.