“gadji beri bimba glandridi laula lonni cadori

gadjama gramma berida bimbala glandri galassassa laulitalomini

gadji beri bin blassa glassala laula lonni cadorsu sassala bim”

These are the opening lines of a poem by Hugo Ball (1886-1927), a German author, poet, and founder of the Dada art movement. The poem is entitled ‘Gadji beri bimba.’ Upon first glance, this poem appears as pure nonsense.

However, let’s look at it differently. Let’s listen to the rhythm these conglomerates of letters form when they slide off the tongue. Let’s analyze the nuances and micro messages.

The second stanza of this poem begins with the phrases “zimzim urullala zimzim urullala zimzim zanzibar zimzalla zam / elifantolim brussala bulomen brussala bulomen tromtata.” These sounds, unlike the ones in the first stanza, seem more lyrical. Additionally, we see words such as “elifantolim brussala,” which, in Latin, means brussel sprouts.

The poem is somewhat comical, too. In phrases such as “gaga di bling blong / gaga blong,” sounds that we’ve heard of such as “gaga” and “bling,” jump out at us, while the other unrecognizable words then mock us. We can also notice alliterative twists that resemble inflection, such as the phrases “beri/ berida,” “bimba/ bimbada/ bimbala,” or “bin/ ban,” showing that Hugo Ball made conscious literary decisions when writing this poem. But, at the same time, maybe it’s important to consider that this poem doesn’t need to have a meaning.

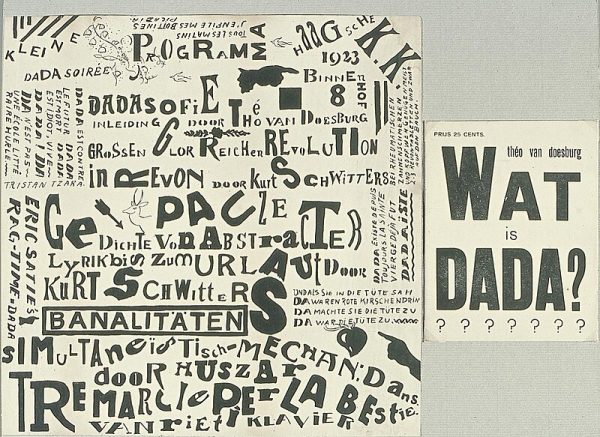

By this point, you may be wondering what exactly Dada is. And though Dadists would condemn you for wondering this, as they’d say that trying to find its origins and meaning ruins the experience, I won’t tease your curiosity any longer.

The Dada art movement was an artistic and literary movement that began in the 20th century as a result of the cultural and social shock that was World War I. In response to this unprecedented event, the Dada movement transgressed the “rules” of art and ventured into the unknown.

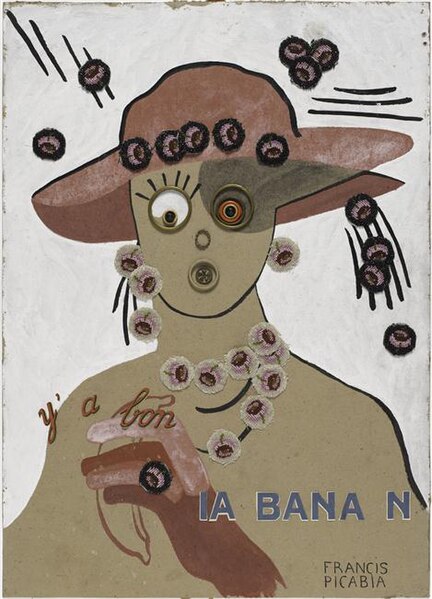

Dada was fundamentally “anti” – anti-aesthetic, anti-establishment, anti-bourgeoisie, anti-capitalism, anti-logic, and essentially anti-art. It called into question everything previously accepted about society and the conventions governing artistic expression. It was humoristic – it mocked humans and society. It was spontaneous and it often leaned towards absurdity. Inspired by cubism and futurism, it challenged the way humans view and depict reality.

And considering the time, this reaction makes sense. Before World War I, it seemed as though people were losing their grip on reality: everything was being questioned. Einstein’s theory of relativity seemed like science fiction. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams claimed that there’s meaning in the subconscious. Schoenberg’s music was atonal. Picasso’s art reconfigured the human form into geometric shapes. Humanity was entering a modern age, which was both worrying and inspiring for many.

Then, between 1914 and 1918 came one of the most tragic experiences in human history: the First World War. It resulted in an unprecedented loss of life and changed world dynamics. But it also represented a complete disintegration in the public’s confidence in the culture of rationality that was growing in the early 20th century. As Freud put it, no event “confused so many of the clearest intelligences, or so thoroughly debased what is highest.”

Where does Dada fit in? Dadaism began in Zurich, Switzerland, in the 1910s. Since Switzerland was neutral in World War I, it became a haven that fostered artists and the creative community. As war raged outside of Switzerland, a cultural war raged inside Switzerland as art and literary works became more experimental, radical, and dissident.

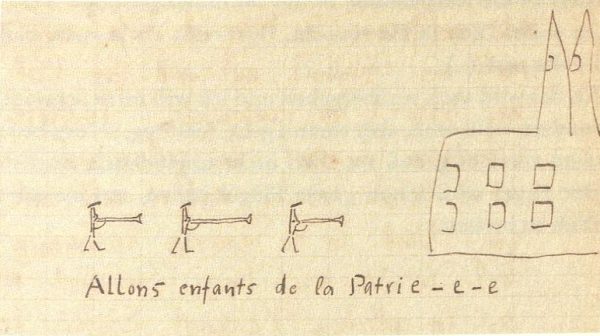

Hans Arp (1886-1966), a Dadaist and abstract artist, put it best. Arp wrote, “Revolted by the butchery of the 1914 World War, we in Zurich devoted ourselves to the arts. While the guns rumbled in the distance, we sang, painted, made collages, and wrote poems with all our might.” In addition to the war Arp writes about, another major cause for the Dada movement was industrialization. Arp would often complain that humans were thought of as mere machines. In response, Dada art mocked that dehumanization.

The epicenter of the Dada movement is the Cabaret Voltaire. The Cabaret Voltaire was founded in 1916 by Hugo Ball and his companion Emmy Hennings (1885-1948), an avant-garde German poet and performer whom he would marry four years later. The cabaret was an artistic nightclub built to foster artists. Thus, the Cabaret Voltaire became a refuge, shielded from the war and violence of the early 1900s, where artists felt inspired to distance themselves from artistic norms and destroy the ideological constrictions in favor of experimental forms of art.

In addition to creating the Cabaret Voltaire, Hugo Ball also wrote the Dada Manifesto in 1916 where he introduced this new phenomenon of ‘Dada.’ He proclaimed, “I don’t want words that other people have invented. All the words are other people’s inventions. I want my own stuff, my own rhythm, and vowels and consonants too, matching the rhythm and all my own.”

Later, he questioned, “Why can’t a tree be called Pluplusch, and Pluplubasch when it has been raining?” In this respect, he isn’t entirely wrong. Centuries ago, we assigned meanings to random assortments of letters and have used them ever since. But why does that giant plant with branches and a trunk have to be called a tree and not a “pluplusch”? Both names are equally preposterous if we look at it objectively.

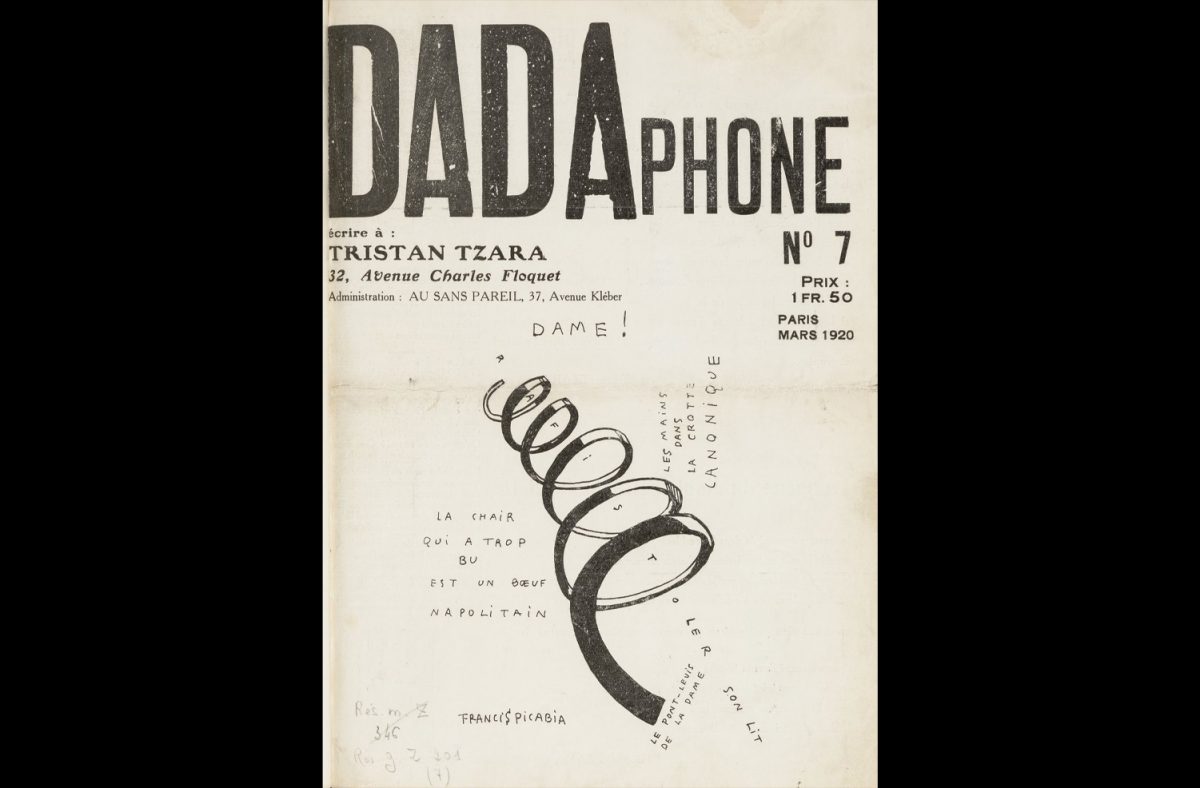

In 1918, Tristan Tzara (1896-1963) wrote his version of the Dada Manifesto. Interestingly enough, his name was originally Samuel Rosenstock, but he legally changed his name to Tristan Tzara as a symbol of breaking away from his previous life. Tzara was a Romanian avant-garde poet, performer, playwright, art collector, and essayist. He is best known as being a cofounder and theoretician of the Dada art movement.

In Tzara’s Dada Manifesto, he declares, “I write this manifesto to show that people can perform contrary actions together while taking one fresh gulp of air; I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense.” Hugo Ball strongly disagreed.

The entire manifesto was written in a frantic frenzy, as though Tzara was exploring the intricacies of philosophy, human nature, and the ever-evolving nature of art whilst drunk on passion. One phrase specifically that resonated with me was when Tzara states, “a work of art is never beautiful by decree, objectively and for all. Hence criticism is useless, it exists only subjectively, for each man separately, without the slightest character of universality.” Sure, we are each entitled to our opinion, but who are we to say what is and isn’t art and what is and isn’t good art?

The creative output of Dada is hard to categorize because artists never stuck to a specific aesthetic. But perhaps one of the most iconic art forms to emerge was the readymade. The term “readymade” was coined by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), a French painter and sculptor, in 1916. It refers to “prefabricated, often mass-produced objects isolated from their intended use and elevated to the status of art by the artist choosing and designating them as such.” He argued that, by choosing to use commonplace objects, the artist was elevating these objects to the status of art.

This new form of art was groundbreaking because it challenged centuries of thinking about the artist’s role as a skilled creator of original handmade objects for art. The readymade also defied the notion that art had to be beautiful. As Hugo Ball wrote, “Ugliness awakens the consciousness and finally leads to recognition of one’s own ugliness,” and perhaps we need to recognize the ugliness around us before appreciating art.

But to truly understand Dada, we must visit its birthplace and core – the Cabaret Voltaire. One can imagine what the cabaret was like. It was revolutionary, dynamic, and iridescent. Jazz and music with African influences pulsed like a heartbeat, the arrhythmic drumming and eccentric notes filling the space. It was often Henning herself who occupied the piano’s seat and brought the Dada soirees to life.

Performances would accompany this music. One type of performance was the primitivist performance, which featured interpretations of non-Western cultures. Today, this is considered problematic, as they used non-Western artifacts from African and Oceanic cultures without recognizing their proper value or distinctions.

Another type of performance was reciting poems. This would be an entire experience, complete with costumes, sounds, and careful intonations. This performance was a sensory and semantic cacophony, especially as the poetry was often made of meaningless phonemes rather than words.

Try imagining a night at the cabaret. The crowd of artists was drunk on power and defiance, infused with a sense of enlightenment as they broke the boundaries of 20th-century thought. Tristan Tzara described the nightly shows as “explosions of elective imbecility.” Energy and expectation filled the air, the constant feeling that something great would be born out of the ashes of the raging war outside Switzerland’s borders.

There was also chaos. As Hans Arp described it, “Tzara is wiggling his behind like the belly of an Oriental dancer. Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping. Madame Hennings, with a Madonna face, is doing the splits. Huelsenbeck is banging away nonstop on the great drum, with Ball accompanying him on the piano, pale as a chalky ghost.”

Surprisingly, the Dada movement spread quickly, like a “virgin microbe,” as Tzara wrote. There were outbreaks in Berlin, Paris, New York, and even Tokyo. It was influential but short-lived. It fizzled because it was only meant to be a state of mind. Ironically, Dada artists became too comfortable with themselves, which was completely wrong for an art form that is all about rejection.

Nevertheless, it left a tangible impact. Surrealism, for example, is one of the prominent art movements inspired by Dada. Surrealism aims to “revolutionize human experience,” particularly by finding meaning in dreams. The artists of this movement see beauty in the uncanny, unexpected, and unconventional.

The 100th anniversary of Dada was celebrated in 2016. Even more than 100 years later, it is still celebrated and has influenced art in the 20th and 21st centuries. And though Dada art hasn’t been created for a long time, the ideas it supported remain. In this day, when violence and industrialization continue, perhaps we can all benefit from revisiting these ideas. Like Dada artists, we must question the norm and proceed to break it. Only then can we create something good.

“Revolted by the butchery of the 1914 World War, we in Zurich devoted ourselves to the arts. While the guns rumbled in the distance, we sang, painted, made collages, and wrote poems with all our might,” wrote Hans Arp (1886-1966), a Dadaist and abstract artist.