The walk to The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art takes you past the American sculpture room, the European Sculpture Court, and then into a little, hidden corner. There, you are transported to a century of photographic history.

Unlike a typical photograph exhibition, which focuses on capturing events of the past, Virginia McBride – a research associate in the MET Department of Photographs – brought these photographs out to show the development of photo advertisement from the 1840s to the 1950s. The changes through each decade bring us to a better understanding of the current state of advertisement, which was McBride’s direct goal.

“Product photography is, now, completely inescapable – it follows you around and stalks you on social media – and that condition is very interesting,” said McBride. The conventions of the past inform these norms and explain the advertisements that we see in our daily lives. F.D. Hampson’s ‘Panama Hats’ is an example of an advertisement that called out for mass consumption. Photographed for a St. Louis sales catalog, these hats feature a surreal, avant-garde arrangement. Here, the display’s practical purpose is clear: showcasing the varied brims and bands invites scrutiny, turning any viewer into a discerning consumer amidst growing choices in this era of increasing consumer choice.

When I visited the exhibition, I was lucky enough to meet Drew, an advertisement photographer who spoke to me about her impressions of The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography. “As someone who works in advertising photography, I find it quite interesting how I think we’ve lost some of the creativity that I see here in this imagery, as far back as the 1920s. It makes me wonder about how I could implement or think about new ways of composition or exploring basic objects in a more exciting way. I’m curious about how these objects were received as advertisements back then. Now, I think we see them more as fine art, so it is interesting to think about what our advertising images could look like twenty years from now.” Drew was strong in her belief that much of the beauty and wonder of advertisement photography has been lost over the decades.

In the 1920s, rising industrial output and consumer demand led executives to seek ways to make their products stand out in a crowded market. Applied psychology shifted managers’ focus to the consumer’s mind, emphasizing the need to persuade consumers that they could find individuality and personal meaning in standardized goods. Consumers “believe what the camera tells them because they know that nothing tells the truth so well.”

This statement holds true, as the camera is supposed to strip down illusions and unearth the bare, pure truth. Under a watchful eye, buyers believe that nothing is being hidden from them. This technique is used in Irving Penn’s ‘Theatre Accident, New York.’ Penn’s goal was to show the personality of a woman without actually showing her. Instead, we see a spilled bag of personal items that have fallen out of her dropped purse, strategically placed and immensely captivating.

“It is such an interesting photo to look at, because you wonder, and you create these stories in your head. Then, it turns out ‘Oh! Everything in the photo is actually for sale!’ That was a fun way for Penn to create this ad. Today, we are much more straightforward. Instead of a composition, we say ‘Here’s this watch on a wrist. Buy it,’” said Drew.

The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography exposes the truth in an entirely new way. It exposes the secrets of photography and how the truth shifted through years of capitalism and consumerism, demanding different sales strategies from producers. “Penn uses lighting that is less harsh, and there is a playful use of shadow. When you look at the modernist art movements taking place during this time with the surrealist inspiration, we don’t have such punctuated movements now as we did in the last century,” said Drew.

Modernism, an early 20th-century movement in art, architecture, and literature, emerged in response to rapid technological, cultural, and societal changes. Innovations like cars, airplanes, and industrial manufacturing reshaped urban life and the public view of the new influx of creations. Artists such as Frederick Bush and Edward Steichen experimented with space and abstraction, highlighting the geometry and dynamism of the material world. They employed extreme angles, tilted horizons, and close-ups, to make viewers see familiar subjects in new ways and to explore the processes of representation and perception. Steichen started incorporating artificial lighting, high contrast, sharp focus, and geometric backgrounds — techniques inspired by fine art and stage photography.

These methods imbue Steichen’s images with a distinctly modernist and innovative quality, which can be seen in his ‘Americana Print: Sugar Lumps’ textile. Bush’s ‘Nothing Rolls Like a Ball’ is distinct in its use of shadow and composition. “The ball-bearing car parts are something that people might not recognize — but the audience is those who know what it is. They see it in a new light and are ready to buy it. However, you can enjoy the image whether or not you know the object,” said Drew. This photograph focuses on three objects caught mid-motion. While there are three tangible metal pieces, there are six in actuality, when including their substantial shadows. Bush uses soft lighting and shadow to captivate his audience and pique their interest, no matter whether they know what it is they are becoming interested in.

In searching for my favorite pieces, delivered by Irving Penn and Frederick Bush, I took it upon myself to ask Drew for hers. Ralph Bartholomew Jr.’s ‘Soap Packaging’ is riveting at first glance. The photograph transforms a few bars of colorful soap into something mouthwatering and elite. This tricolor printing technique became famous in the 1930s as Depression-era artists worked to bring color to consumers’ lives. “The color and composition is unrivaled,” said Drew. Brilliant color catches the eye; soap packaging is a booming industry, a commodity.

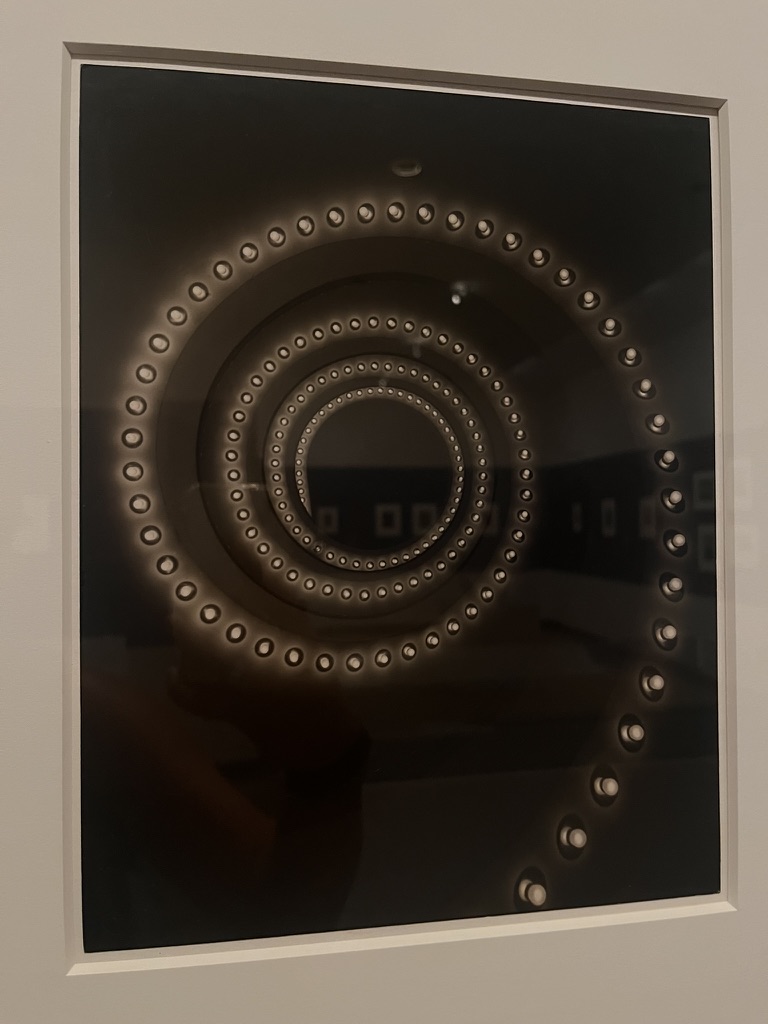

August Sander’s ‘Osram Light Bulbs’ combined the camera’s codependence on artificial light with the sales of a lightbulb company. Illumination is transformative; with electricity and one bulb of light, a concept not truly understood by consumers of the time, an entire room could brighten. Sander shifted their perspective. Now, there was a looming, shining, illuminated stairway up. The lightbulbs became a swirl of pearls touching the sky and pleasing the eye simultaneously.

As you travel through the decades in The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography, technique and style change. For me, it was not until I came upon Murray Duitz’s ‘A.S. Beck Executive Shoe’ that I fully understood the change which Drew had mentioned in the modern advertisement. Here, the exhibition does not display a work of color and composition. There are no playful shadows or lighting that catches the eye.

In 1957, Muitz photographed a model and showed us an age of advertisement with which we are familiar. This particular technique still exists today in the idea of “Here’s this watch on a wrist. Buy it.” As the American capitalist market demanded printed ads and mass consumption increased, photographers lost their creative control, with advertisement directors taking up the mantle. There is a straightforward appeal and very little left to the imagination.

Whether or not you find yourself drawn to artwork, museums, or photography, I encourage you to take a step out of your comfort zone and experience this exhibition. While it is small, it is incredibly moving and thought-provoking. It is composed of works with which we are familiar, despite not having seen them before. Advertisements are all around us, and their development is illuminating. The psychological and emotional appeal of these photographs and the straightforward and clever approach of each decade speaks directly to us, the consumer. I implore you to imagine, to wonder, and to see what you might learn from it. This exhibition will be open until Sunday, August 4th, 2024 in Gallery 852 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. If you find yourself with an hour of free time and are craving a new experience, check out The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

Consumers “believe what the camera tells them because they know that nothing tells the truth so well.”