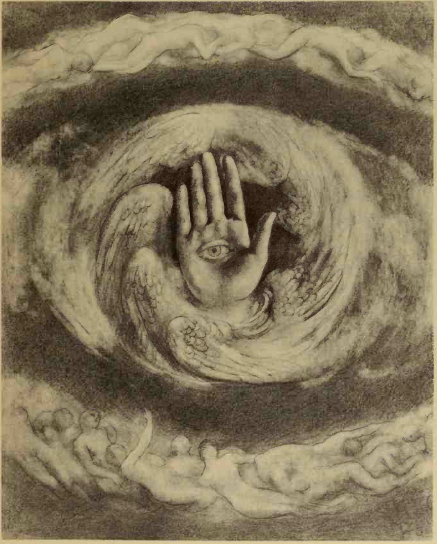

When I first stumbled upon The Prophet, I did not know what to think of it. The copy was miniature and portable, fitting just right into the deep corners of my pocket; the cover was turquoise, the title gilded in gold. The centerpiece was minimalistic, with what looked like ocean waves lining a hand, an eye at the center of it. I wondered what it meant.

Even the name of the book was peculiar. My first thought was that it must be about religion. As I borrowed the book from the library, not having read the synopsis, I did not realize that I was in for a transformative experience, my perception of the world enhanced by one man’s words.

The Man Behind The Prophet

Before reading the novel, I desired to learn more about the author behind the work of art: Kahlil Gibran.

Born in northern Lebanon in early 1883, Gibran Kahlil Gibran (his birth name before being changed to Kahlil Gibran) was raised alongside two younger sisters by his parents, Kamileh and Kahlil, living a rather difficult life in poverty. Despite this, they continued through the motions of life, persevering.

Lebanon housed a number of people from different backgrounds and religions, including Armenians, Christian Maronites, Jews, Greek and Syrian Catholics, as well as Shi’a and Sunni Muslims. Until 1860, when a civil war between those who identified with the Druze religion (associated with Islam) and the Christian Maronites had reached its boiling point, all the religions had lived in relative peace, with the exception of minor conflicts along the way.

Sectarian conflicts set the stage for Gibran’s life in Lebanon and influenced several of his works, including Spirits Rebellious, a collection of four stories with an overarching theme of social justice and spirituality. Kahlil Gibran has often mentioned religion in other works, and in The Prophet, hints of religion continued to echo.

This can be attributed to the idea that although Gibran was brought up as a Christian Maronite, he was influenced by Islam and Sufism, which focuses on spirituality and the relationship with one’s mind. Gibran believed that all religions should find the unity they once had before, and the methodology in which he wrote distinguished this belief.

Kahlil Gibran’s travels and experiences throughout his life left him with a new sense of how the world should be approached. Gibran recognized the holiness underneath the land on which he walked and felt a strong connection to discovering the meaning of life, drawing him closer to the words of the prominent philosopher Frederich Nietzche. Although Nietzsche famously proclaimed the phrase “God is dead,” in a philosophical fiction of his own, Gibran did not exhibit the same feelings towards religion, instead embracing spirituality through his writing as well as through his art. From a young age, Gibran unleashed his creativity with the meager bits and pieces of charcoal he could find to write with.

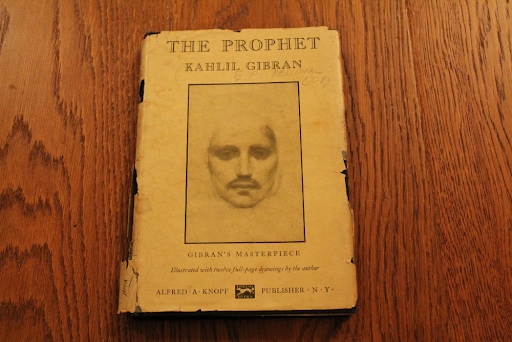

By the time of his death on April 10th, 1931, in a Manhattan hospital where he succumbed to tuberculosis, Gibran had written nearly forty literary pieces. Some were written in his mother tongue, Arabic, while others were written in the language he had adopted after entering America, English. His love for art manifested itself in over 700 artistic creations, many of which can be seen amidst his novels.

An Introduction to The Prophet

Published in 1923, The Prophet is a collection of twenty-six essays told from the eyes of Al-Mustafa, a prophet in the city of Orphalese. Al-Mustafa has been waiting twelve years to return back to the island of his birth, having repeated premonitions of a ship arriving to take him away. When his dream finally manifests into a reality, Al-Mustafa feels a deep sadness in his heart, a bittersweetness that plagues his entire being.

Orphalese is not home to him, but rather a fond memory, like a soft blanket placed over him until the time comes for him to rip it away. When Al-Mustafa nearly makes peace with a goodbye to the city and its people, both of which have housed his struggles and joys, Almitra, a seeress, comes up to him. She wants him to do one thing and one thing only: speak his truth so that his truth may be passed down generations and never perish.

And so begins the one hundred and seven-page journey of philosophical advice and sermons that Al-Mustafa guides the villagers and readers through, under the skillful pen of Kahlil Gibran, a master of his trade.

The Lessons Within The Prophet

Each poem lends its own lesson, and except for ‘The Coming of the Ship’ and the final poem, ‘Farewell,’ the names of the poems have fairly simple and thematic names, such as ‘On Crime and Punishment’ or ‘On Religion.’

It is interesting to notice that the first poem is on the notion of love and the last poem is on death. Love and death are so deeply intertwined that Gibran develops this connection further into the rest of the poems. To love is to live, and the death of love is death in and of itself.

Al-Mustafa believes that a person must feel love in its entirety, for love cannot be possessed nor contained. Only then will one be able to appreciate love and life for what it is. Gibran describes love as a power that is transformative; it has the ability to change a person’s life for better or for worse, a juxtaposition. These sentiments are only developed when themes pertaining to love are introduced in The Prophet.

With love follows marriage, a binding contract that society often looks towards as a source of strength and validity — becoming one with another. Despite this eternal and pure connection between two lovers, Al-Mustafa reiterates: do not let your being overwhelm the other. You must stand strong but apart at the same time. You need to possess your own innate awareness of who you are and where you stand, with or without a person by your side.

To accompany this, Gibran used a fair amount of metaphors including musical instruments and holy sites; even “as the string of a lute are alone, though they quiver with the same music” and “the pillars of the temple stand apart,” growing not in each object’s shadow. The pillars hold the holy temple up and yet they stand apart, promoting the notion that to be stable is to have the strength to be together and yet alone at the same time. Only then can one’s way of loving the other truly unfold.

The next step of life following marriage is often parenthood, a responsibility that remains a learning curve. Parents often strive to mold their children into a version of themselves, unaware or ignorant of the idea that while their children are from them, their minds cannot be possessed. As Al-Mustafa put it, “You may give them your heart but not your thoughts.”

Al-Mustafa compares the archer, bow, and arrow scenario to parenthood, encapsulating the ideal nature of parenthood as it should exist. The archer is God, the parent is the bow, and the child is the arrow. “He bends you with His Might that His arrows may go swift and far.” After an individual is made to be a parent, they are responsible for the upbringing of their children, ensuring that their role in the present may shape their child’s life in the future.

In all these stages of life; however, emotions will always remain the same: joy and sorrow. Both joy and sorrow are themes that complement one another, relating to the seamless juxtaposition that is life and death. While one can experience joy to the highest of their ability, one can also experience sorrow of the same caliber. “Your joy is your sorrow unmasked,” Al-Mustafa reflects, meaning that the root of sorrow and joy is the same.

Gibran also touches upon freedom and its necessity for the villagers in the book, but urges ordinary humans in real life to “worship” the idea of freedom. When people desire freedom too much, they become chained to freedom. It is a paradox; in order to free oneself from the freedom that they have shackled themselves to, a person must transcend into true freedom which exists when an individual is above yearning, to discard the aspects of life that are so intertwined with their existence.

Another theme that cannot be altered or discarded is time. Time continues with or without an individual. Many often seek to ‘control time,’ hyper focusing on the ways that they can utilize their time without actually putting it into effect. Here, Al-Mustafa focuses on the idea that the present does not stand by itself but receives its strength from the past, as does the future from the present, its own past. In each lesson, there is a growing motif that humans do not realize that they exist in a world that is far more vast than their own place in it.

We as humans get so incredibly caught up with our lives and picking apart aspects of life that can feel taxing on us, forgetting the wonders and visions that life has to offer, forgetting that joy and sorrow come in one package.

The human condition is vast, and the way humans operate is something that scientists and philosophers, amongst other professions, continue to learn every day. Gibran’s words lend an anchor to the spiritual side of oneself, urging us to let go of ourselves and understand the moment, to express gratitude for who we are and what we stand for.

The Impact of The Prophet

The Prophet has never been out of print. Sentences and phrases have been reused in events that mark milestones in the lives of individuals, including both weddings and funerals. Kahlil Gibran has left a presence after his passing that cannot go unignored.

In a world we live in, plagued by war, greed, and bigotry, Gibran intends for his readers, much like the villagers in Al-Mustafa’s world, to find solace. He wants us to understand that while our place in this world is minuscule and the world is a far greater place than we can ever be, we must tread this world with a simple outlook, to lead with joy and learn that we can only truly live when seeing past the materials this world has to offer.

Only then will you realize your sole purpose in life, “for life and death are one, even as the river and the sea are one.”

We as humans get so incredibly caught up with our lives and picking apart aspects of life that can feel taxing on us, forgetting the wonders and visions that life has to offer, forgetting that joy and sorrow come in one package.