Articles from 2024 will still name Do the Right Thing as one of the ten or twenty must-watch movies about race. Do the Right Thing is a movie about the hottest day of the year in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It was released and nominated for an Academy Award as Best Picture in 1989 and was directed by Spike Lee.

In articles or interviews about Do the Right Thing, the most common explanation for its enduring relevance is its depiction of police brutality, a problem that has only grown since 1989. This is true, but its lasting impact on viewers goes beyond this.

Initially, I thought it may be Do the Right Thing’s striking visuals that set it apart from most movies (let alone movies about race). The opening scene of Do the Right Thing is explosive. Silhouettes of Tina’s (played by Rosie Perez) fighting stances dart across the screen, morphing into electric dancing against a moody red background and the tune of ‘Fight the Power,’ the anthem of the movie written for Lee by Public Enemy.

I thought it may also be Do the Right Thing’s attention to detail. The setting of the movie is a block in Brooklyn, which is now named “Do the Right Thing Way.” Lee chose to paint one brick wall red because “they wanted people sweating.” Across the street from Sal’s Pizzeria, there is a mural with Puerto Rican, Jamaican, American, and an Afro-American flag, above which it says “BED – STUY – DO OR DIE.” At one point, the character Buggin’ Out tries to organize a boycott of Sal’s Pizzeria in front of a poster of “Brooklyn’s Own Mike Tyson.” Once, on a delivery, Mookie (played by Lee) holds pizza boxes in front of Jesse Jackson 1988 presidential campaign posters. It seems no coincidence that the white cyclist who recently moved into the neighborhood — the beginning of gentrification — wore a Larry Bird jersey. In one scene where Mookie tells Jade to avoid Sal, “Tawana told the truth” is spray-painted on the wall behind them. Tawana Brawley is an African American woman who became a household name in 1987 when, at 15 years old, she accused 6 white men of horrendous crimes against her. The case caused intense racial tensions and Brawley gained support from well-known Black Americans – including Reverend Al Sharpton, Bill Cosby, Don King, and Louis Farrakhan. The more you pay attention to the film’s setting, the more you learn about New York and Bed-Stuy in 1989.

But beyond Do the Right Thing‘s attention to details and visuals, there are three more factors that explain a unique impact on viewers. It depicts multidimensional characters, shows love and hate both within and between racial groups, and doesn’t end with a single verdict.

The characters are multidimensional

Tina is introduced in the movie’s fiery opening dance sequence to the song Fight the Power. Buggin’ Out or Radio Raheem would have been a more obvious choice for the opening scene because they persistently try to gain representation for Black people on Sal’s wall of fame, or by playing rap music. The background of Tina’s dance is the block, which is also interesting because in the movie Tina never leaves her house. We only see her argue with her mother, Mookie, and care for her son. Upon first glance, the obvious interpretation would be that she is fighting white police officers – there are red, blue, and white lights flashing in the background. But the contradiction between Tina’s dance and her story in the movie challenge this idea. Tina never comes into contact with police officers. She could be fighting Mookie, an absent father who only appears when he wants to “do the nasty.” She could be fighting the sexism implicit in that relationship; however, it’s an overtly sexual dance, casting doubt on the idea that Tina might be fighting sexism. Although unanswered, the question of why Tina was chosen for the opening sequence highlights the intention to bring an overlooked character into the spotlight.

Mookie (played by Lee) is a Black pizza deliverer for Sal. He gets along with Sal and his son Vito, and doesn’t lose patience with Sal’s other son Pino, who is blatantly racist. Mookie is beloved by Mother Sister, Buggin’ Out, Radio Raheem, Love Daddy, and Jade. However, Mookie isn’t made to seem perfect. He verges on losing his job because he takes long showers in the middle of the day after his deliveries, and dallies rather than reporting back to Sal’s pizzeria. Mookie also has a girlfriend and son who he financially supports, but he only visits them once a week. But Mookie’s failings humanize him, and we root for him as he juggles his job, relationships, and racial dynamics. Mookie has to balance what it means to be Black and work for an Italian-American business. Once, Mookie has to escort Buggin’ Out out of Sal’s pizzeria because Sal became angry with Buggin’ Out. Buggin’ Out told Mookie to “stay Black” and Sal asked Mookie to control his friend. Mookie balances appeasing his Black friends and Sal and his sons the whole movie, which is why his final decision to throw the trash can is so fateful.

Da Mayor is an African American man who is always either drinking a beer or hunting down another beer. Despite struggling with alcoholism, Da Mayor is always compassionate to the people in the neighborhood. Despite Mother Sister being mean to him, he continues to woo her with roses and compliments. While people in the neighborhood regard him as an incapable drunk, he saves a young boy from being hit by a car. At the end of the movie, he tries to stop the mob from destroying and looting Sal’s pizzeria.

Sal is the Italian American pizza store owner, and he’s one of the most complicated characters in the film, as well as one of the most important to understand. Usually, Sal defuses situations; he tells Pino to stop pestering Mookie and tells Pino and Vito to stop fighting. Sal loves his business, whether it’s because he is committed to the community or because he loves his success in building and growing his business. When Pino says that he “detests this place (the pizzeria) like a sickness,” Sal is offended. When Sal and Pino talk alone, Pino uses derogatory terms for the community’s residents and asks Sal if they can open a pizzeria in their own neighborhood, but Sal refuses. He tells Pino there are already too many pizzerias in their neighborhood, and that he is proud of the business he has built, which has served the pizza people in Bed-Stuy throughout their lives.

Sal also seems to like the people in Bed-Stuy. Sal says hi to the Korean business owners in the morning, making him the only character in the movie to treat them genially. Every day, Sal pays Da Mayor to sweep the sidewalk, something he could have his sons do for free. He has a big crush on Mookie’s sister, Jade. He looks out for Mookie, telling him he needs to get his act together to keep his job. Near the end of the movie he tells Mookie, “There will always be a place for you at Sal’s Famous Pizzeria.”

By defusing conflicts and being warm to the people who live in Bed-Stuy, Sal garners our sympathy. However, his politeness goes only so far. He resists responding to the desires of the community. This is apparent in the two central conflicts in the movie.

Buggin’ Out believes that because Sal makes his money selling pizza to Black people, it’s only right that they are represented on Sal’s wall of fame, which has pictures of famous Italian-Americans like Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio. Sal believes that because he owns the business, he should decide what goes up on the wall. With Raheem, he is unwilling to let him play hip-hop music.

In the conflicts with Buggin’ Out, Raheem, and the whole movie, pop culture plays a huge role. Once, Mookie asks Pino why he hates Black people, despite the fact that his favorite basketball player is Magic Johnson, his favorite movie star is Eddie Murphy, and his favorite rock star is Prince. “It’s different. Magic, Eddie, Prince are…not Black. I mean, they’re Black but not really Black. They’re more than Black.,” Pino responds. Throughout Pino’s life, Black culture has been integrated with American culture, yet he is still racist and disrespects the people of color in the community.

This is not the case for Sal. While Sal respects and gets along with the people in Bed-Stuy, when Buggin’ Out first asks if Sal can put some Black people up on the wall of fame, Sal becomes angry, brings out his Mickey Mantle baseball bat, and asks “You a troublemaker?” Vito tells his dad to relax, and Pino, who is usually openly bigoted and worsens conflicts, takes away the bat from his dad. Despite Pino being as racist as Sal, he has grown up in a time when the idea of a wall of fame with Italian Americans and Black Americans wasn’t as unusual to him. The idea was repulsive to Sal.

At the climax of the movie, Raheem enters the pizzeria and blasts his hip-hop music. When Raheem continues to play his music despite Sal’s wishes, Sal responds with a racist comment. The argument heats up, and Sal responds with racist epithets.

Then Sal takes his Mickey Mantle baseball bat and smashes Raheem’s Boombox, cutting “Fight the Power” off, and leaving us with only the sounds of the bat crushing the boombox. Sal silenced Raheem’s voice of activism, and his pride and joy; he silenced the anthem of Do the Right Thing. In some ways, it represents the soul of Bed-Stuy-Do-or-Die, and Sal silenced it.

Previously, tense arguments fizzled out, but this argument seems to have revealed Sal’s true thoughts. He demeaned and reduced his customers to a slur. Now, it doesn’t seem possible to return to the old status quo.

Before the conflict, there was mutual goodwill between Sal and the people in Bed-Stuy. But Sal couldn’t agree with the idea of Black people being fully integrated into society – he didn’t want to listen to Black music or have Black people in his wall of fame.

Later in the movie, we also see varying standpoints among the cops. While all are bigoted, one cop strangles Raheem while another cop says, “Gary that’s enough” multiple times to try to stop another cop from killing Raheem.

Love and Hate – Within and Between Racial Groups

The relationships in this movie can be understood through the the opposing themes of love and hate. Lee makes this clear in one scene. Raheem encounters Mookie on the way to deliver a pizza. Raheem clenches his fists for Mookie, presenting his twin rings. Each span all four fingers; the left ring says “LOVE” and the right says “HATE.”

Raheem tells Mookie, “The story of Life is this…Left Hand Hate is kicking much ass and it looks like Right Hand Love is finished. Hold up. Stop the presses! Love is coming back, yes, it’s Love. Love has won. Left Hand Hate KO’ed by Love.”

It seems that Raheem advocates for love within and between racial groups.

But then Raheem’s ideas on love and hate become more complicated when he tells Mookie, “Brother, Mookie, if I love you I love you, but if I hate you…”.

Raheem trails off, transforming a powerful speech about the power of love against all odds into a cliffhanger. Then, he disrespects Korean business owners. Raheem visits a deli in his neighborhood, run by a Korean family who recently immigrated to the U.S. He is trying to buy D batteries, and when they confuse his ‘Ds’ for ‘Cs’, he yells D many times, and then yells, “Learn how to speak English.”

Later, Raheem approaches a group of young Puerto Ricans playing music. His boombox, which he carries everywhere, is louder than theirs. So they turn up their music. He turns up his music again, and this time it’s much too loud for them to overpower. Raheem didn’t believe their music, which was symbolic of their respective cultures, should coexist. He wanted hip-hop to overpower Puerto Rican music. This hostility goes both ways – the group of Puerto Ricans does not like Raheem either.

However, there’s also love between racial groups.

Mookie’s relationship with Tina is complicated: he’s an absent father, he yells at his mother-in-law to speak English at home because it’s “bad enough my (his) son’s named Hector,” but also likes Tina and tries to be more present. While Pino and Mookie don’t have a positive relationship, Mookie is friends with Vito and gets along well with Sal (for most of the movie). Mookie is also friends with Smiley, an intellectually disabled white man who tries to sell pictures of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X shaking hands. Mookie’s interracial relationships also speak to his loving and easygoing character. Unlike Buggin’ Out and Raheem, Mookie is willing to get along with Sal and his sons — partly because he must for his job and partly because that’s who he is.

And hate isn’t exclusive to interracial relationships. Mother Sister displays open contempt for Da Mayor because he is an alcoholic (she calls him “you ole drunk” or “drunk fool”) and he reminds her of her ex-husband.

Lee also depicts interracial relationships as ever changing. At the beginning of the film, the Korean deli owners are treated disrespectfully. After Sal’s business is destroyed, it looks like the mob is about to destroy their deli when the Korean clerk says, “Me no white. Me no white. Me Black. Me Black. Me Black.” At first, the mob begins to laugh and it seems like the Korean business will be looted as well, but instead, Sweet Willie, ML, and Coconut Sid (the three men who sit on the corner and gossip during the day), agree and say “Him Black. Him Black.” This changes the mob’s opinion.

This is a significant shift in the relationship from earlier in the movie. While earlier the corner men had complained that there was a Korean business in the neighborhood while there was no Black business, now the corner men have acknowledged the Korean family as another group that lacks power and representation. The corner men have divided the community into those that have power and those that don’t: Sal, his sons, and the police officers versus the Korean business owners, the Black people, and the Puerto Rican people in the neighborhood.

There’s no single verdict

At the end of the movie, Lee doesn’t try to lead us to a single opinion about whether Mookie did the right thing by throwing the trash can.

Firstly, it’s unclear whether Sal and his sons are to blame for Raheem’s death (in addition to the police). Sal began the confrontation by asking Raheem to turn the music off, using racial slurs, and destroying Raheem’s boombox, but Raheem was the first to start a physical fight by strangling Sal. Vito was the one who called the police, but his decision was understandable. He was watching his father being choked. The only ultimate wrong in the end was the police brutality depicted.

Mookie must have contemplated all of this and more, and felt rage at the death of his friend Raheem when he threw the trash can.

What makes the end interesting is that there are two reasonable ways to view Mookie’s decision.

Mookie’s job is important to him. When we meet Mookie, he is counting his bills from the week prior, and he tells his friends to get jobs. Mookie is (as far as we can see in the movie) the only Black or Puerto Rican person to have a job. So we can interpret Mookie’s decision to throw the can as a sign of integrity that Mookie would choose what he thought was best for the community over his job, rather than as a desire for violence or destruction.

But, Mookie’s choice also makes us contemplate the role of violence in progress. Removing Sal from the neighborhood after it became clear he was racist could be interpreted as a necessary act. However, the neighborhood lost its pizzeria. And destroying Sal’s business didn’t bring back Raheem’s life, or prevent further acts of police brutality.

The way Lee chooses to end the movie is also reflective of his conscious opt for complexity. After the riot has left the pizzeria destroyed and burning, Smiley pins up a picture of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King on the wall.

Lee could have chosen to end the movie on that note, with Black people finally displayed on the wall of fame, a racist person’s business destroyed, and Fight the Power still playing, despite the damage to the boombox. Some people in the community must have felt they avenged the death of Raheem. But the community has to wake up the next day and face the consequences of their actions — and so Lee forces us to do the same. The next morning, Mookie walks to Sal’s pizzeria and asks for his pay. We see the paper napkins and trash strewn across the entire neighborhood and Sal’s pizzeria devastated.

Mookie and Sal argue about who caused Raheem’s death and about Mookie’s pay. Eventually, Sal says, “They say it’s gonna get even hotter today. What you gonna do with yourself?” with a tone of genuine concern for Mookie.

The argument and the destruction to the neighborhood shows us that the riot didn’t help the community reach a final verdict on Raheem’s death, and the heat — which represents racial tensions and global warming — continue to persist in Bed-Stuy. Together, they make us question the purpose and benefits of the riot.

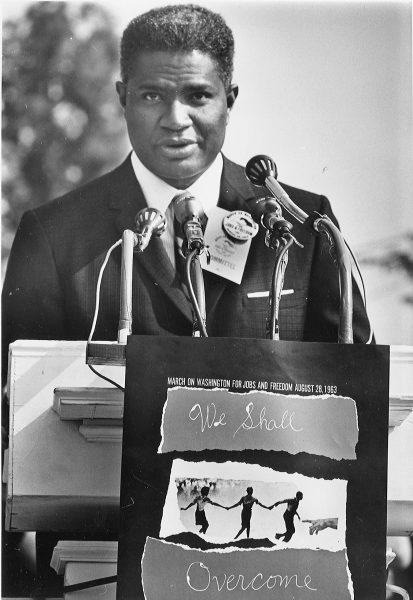

The finale of the movie is two quotes, one from Martin Luther King, and the other from Malcolm X.

“Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by destroying itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn’t mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self- defense, I call it intelligence.” — Malcolm X

“For drama, you gotta have two people butting heads. And it elevates the drama when they’re both right.” Lee once said. This principle is the backbone of the movie. Lee sought to spark discussions about race when he released the film in 1989 and it’s had an enduring impact because it refuses to simplify issues.

Articles from 2024 will still name Do the Right Thing as one of the ten or twenty must-watch movies about race. Do the Right Thing is a movie about the hottest day of the year in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It was released and nominated for an Academy Award as Best Picture in 1989 and was directed by Spike Lee.