“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.”

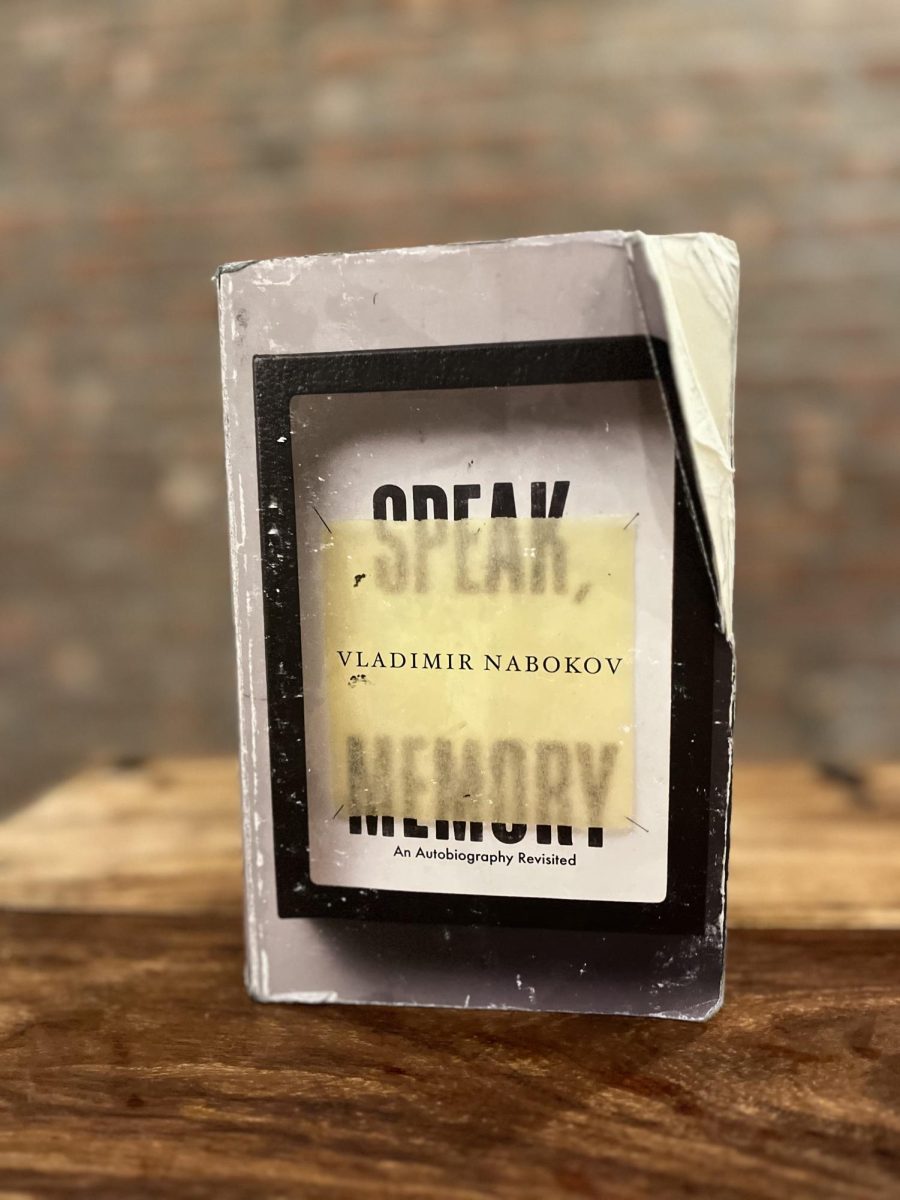

Thus begins Vladimir Nabokov’s autobiography, Speak, Memory, which embarks on the ambitious attempt of making sense of such light; the meaning of life, and specifically, the meaning behind his own life.

Speak, Memory was published in 1951, and up until then, Nabokov’s life had proceeded as follows. He was born in 1899 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, into a wealthy, esteemed family of the Russian nobility. He grew up surrounded by tutors and spoke three languages, Russian, English and French. His life of privilege came crashing down during the Russian Revolution of 1917 where Lenin’s Bolsheviks were launching an armed, socialist revolt. Nabokov’s family fled Russia and sought exile in Europe; Nabokov went to study at Cambridge.

After university, Nabokov joined his father in Berlin. Soon after, his father was assassinated by Russian monarchists, an event which traumatized Nabokov severely. As years went by, his career as a writer and poet began to bloom, and he married Véra Evseyevna Slonim. Together they had their only child, Dmitri Nabokov, and in 1937 the family moved to France, and eventually the United States. Nabokov became a professor at Wellesley University, which is where he eventuallywrote, Speak, Memory, and later, his arguably more famous literary contribution, Lolita.

And in reflecting upon this life-lived, Nabokov writes in Speak, Memory: “Neither in environment nor heredity can I find the exact instrument that fashioned me, the anonymous roller that pressed upon my life a certain intricate watermark whose unique design becomes visible when the lamp of art is made to shine through life’s foolscap.”

In essence, Nabokov comes to the conclusion that he must turn his life into art so that he may understand it. Thus was the reason he decided to write the autobiography. And he turns to his memories to do so.

“The following of such thematic designs through one’s life should be, I think, the true purpose of autobiography,” wrote Nabokov.

And as Nabokov parcels diligently through his life, many themes appear. Water, war, trauma from his father’s death, and exile are notable among them. Identifying these themes was Nabokov’s key towards unlocking the pain which weighs on his subconscious.

Nabokov will recount a memory, and interweave it with analytical prose. The product of this practice is an artistic understanding of self; where overarching poetry is found within times that felt seemingly lost.

For example, Nabokov revisits the theme of exile in Chapter’s One, Nine and Ten respectively:

“But their indomitable will to blot out the past, block by block, and their naive assumption that life can ever be rebuilt like a ruined edifice, are among the constant factors of exile.”

“The antipodal obsession, exile, the lover’s and the prisoner’s hunger for the coast of home, distant home, promised land, dreamland, lost Atlantis”

“That creaking door I remember! That door, that threshold, the tears of things, the heartrending alienation of objects and places as they persistently remain behind the times… the fixed stars of exile.”

The addition of poetic rhetoric elevates his memories and romanticizes his life. This quality adds a novel-like feel to Nabokov’s narration, which was very intentional:

“This will be a new kind of autobiography,” Nabokov wrote to an editor, “or rather a hybrid between that and a novel.”

Nabokov takes the idea of a hybrid autobiography even further, and in any passages incorporating fiction into his recollections.

From Chapter One: Portrait of My Mother, he writes:

“The dimmest of my father’s visits to Vyra coincides with the arrival of a governess—a Miss Norcott, who must have arrived on the same day, in the same train, and lived in the same cottage, as in the plot of ‘Mansfield Park’… The gentle reader will never know, by my fault, how the memory of a Russian winter night, or the image of my mother, makes a summer twilight in the English countryside—’nearer, my God, to thee.’”

Nabokov intertwines his memory of his mother with a fictional setting reminiscent of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. By blending elements of fiction with his recollection, Nabokov creates a vivid and artistic portrayal of his mother’s presence.

From Chapter Six: Colette, he writes:

“At some stage of my youth, while roaming through the dusty rooms of our old family house, perhaps in search of my round-collared sailor suit, or of my diminutive Russian dictionary, I must have happened upon a tiny volume… A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life, I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers.”

Here, Nabokov merges the act of reminiscing about his childhood home with a fictional encounter involving a book. This blending of reality and imagination underscores the intricate nature of memory and its intersection with art.

From Chapter Sixteen: First Russian Verses, he writes:

“I was then living in a large grey house in a quaint small town with one steep cobbled street down which clanged a big black bus; and I was deeply in love with a fair-haired girl, queen of my class, who one day would come riding her bicycle through sunshine and shower, a dreamy coed in red stockings, ripe and ready to be plucked.”

In this passage, Nabokov paints a vivid picture of his youthful infatuation with a classmate, blending personal memory with imaginative embellishments. By intertwining elements of reality with fictionalized details, Nabokov crafts a poetic and evocative portrayal of his past.

Many of the pictures Nabokov paints with his memories are sweeping. His life becomes a romanticized fantasy, and the reader does not want to leave. The lowest points of any person’s life are felt with such pain because the source is difficult to easily trace. Only when one drills through their memories to unlock the poetic narrative that was forming below the surface, do they realize that the epic lows and highs, and everything in between, is really just a piece of art if framed correctly.

Just as reading Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, is a moving piece of art within itself, its secondary gift is to help us realize that all our lives are art if we know where to look.

Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory has left an indelible mark on literature, influencing writers and shaping the literary landscape of the 21st century. Published in 1951, this memoir stands as a masterpiece of autobiographical writing, celebrated for its lyrical prose, innovative structure, and profound exploration of memory and identity. Its impact on contemporary literature is profound and far-reaching.

In the 21st century, Nabokov’s Speak, Memory continues to inspire writers across genres. Its intricate narrative techniques, which blend fact with fiction and memory with imagination, have influenced contemporary memoirists, novelists, and essayists. Writers such as Julian Barnes, Salman Rushdie, and David Mitchell have drawn upon Nabokov’s stylistic innovations and thematic depth in their own works, crafting narratives that blur the boundaries between reality and fiction, past and present.

Moreover, Speak, Memory has contributed to the ongoing conversation about the nature of memory and the construction of personal narratives in literature. In an age marked by the proliferation of digital media and the democratization of storytelling, Nabokov’s exploration of memory as a subjective and mutable phenomenon remains as relevant as ever. His memoir reminds readers of the power of storytelling to shape our understanding of the past and ourselves, inspiring a new generation of writers to delve into the complexities of memory and identity in their own work.

“This will be a new kind of autobiography,” Nabokov wrote to an editor, “or rather a hybrid between that and a novel.”