A young Chinese-American girl looked on with bright eyes as hoards of glamorous directors, cameramen, and actresses infiltrated her neighborhood with cameras and blinding lights, busying themselves with producing the next Hollywood blockbuster. This young girl was Wong Liu Tsong, who would become the first Chinese-American film star in global cinema.

Anna May Wong

Wong Liu Tsong was born to two Chinese immigrants in 1905, in the Chinatown of Los Angeles, California. Often facing racist taunts from her peers, movies became her source of comfort and refuge. Soon, she was skipping school to explore movie sets and quickly came to the resolve that she would return to these sets as an actress.

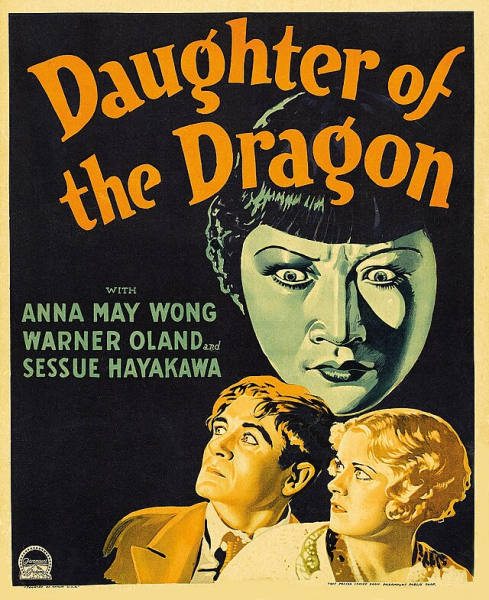

Following the Opium Wars, the film industry was an especially daunting world to enter for Chinese-Americans, as productions almost always reflected “yellow peril” propaganda, which portrayed Chinese characters as addicts and criminals. In fact, landing roles as a Chinese-American was near impossible, as yellow face was preferred, where white performers played characters of Chinese origin.

Despite the disadvantages, Wong persisted, and landed her first role as an extra in the 1919 silent film “The Red Lantern.” However, to Wong’s disappointment, she had less than a minute of screen time, playing a girl with a lantern. All the lead roles were snagged by white actresses, who used makeup to artificially elongate their eyes.

Despite this marginalization, Wong continued to chase after significant roles under a new name, Anna May Wong. This process of Americanization would later come to define her decades-long career. She was trapped by the necessity to appear American enough to appease the white public, but still exude a foreign air of mystique to attract viewers.

In 1922, she landed her first lead role in The Toll of the Sea, a silent film remake of the Italian opera Madama Butterfly. The plot followed the tragic story of a young Japanese girl, Cio-Cio San, who falls in love with a high-handed American naval officer. Shortly after their marriage and the birth of their child, he abandons her to marry an American woman. For the rest of the film, her identity is consumed by his absence, and she dutifully awaits his return.

To portray the role of Cio-Cio San, the directors had Wong do more crying than acting.

Wong’s confinement into stereotypical roles never dampened the pride she held for her Chinese heritage. She never allowed herself to be limited by her docile roles in silent films, instead asserting herself with defiance and personality in real life. Her true character was evident in all her interviews, where she often toyed with ignorant viewers, playfully switching between English and Cantonese to shock and confuse them.

In one of these interviews, Wong said, “I was so tired of the parts I had to play. Why is it that the screen Chinese is nearly always the villain of the piece, and so cruel a villain – murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass. We are not like that…We have our own virtues. We have our rigid code of behavior, of honor. Why do they never show these on the screen? Why should we always scheme, rob, kill?” Wong always believed she was worth and meant for more, and by her death in 1961, she left thousands of Chinese-Americans across the country with new dreams to fulfill.

These dreams became reality as a rush of bracing works, quite literally, fought through the mainstream.

Cue the rise of Bruce Lee and martial arts films.

In the late 1960s, American-born Chinese baby boomers were coming of age, and they began to challenge America’s deep-rooted anti-Asian sentiments. Inspired by the radical ideas of the time’s civil rights movement, a Chinese-American movement was born. Various Chinese-American organizations across the country, particularly in California and New York, advocated for increased opportunity and respect for their heritage cultures.

As American-born Chinese (ABCs) promoted an understanding of their native traditions, mainstream Americans began to develop an interest in the more faddish aspects of Asian culture, namely martial arts.

Martial arts movies had always been popular in China, used as a storytelling device to preach the Confucian values of respect and righteousness. However, it was almost unbeknownst to Western audiences, who were first exposed to the genre through Chinatown cinemas – and scarcely so, since there were only fifty Chinatown cinemas across the United States. The true turning point in the martial arts genre would be credited to Bruce Lee.

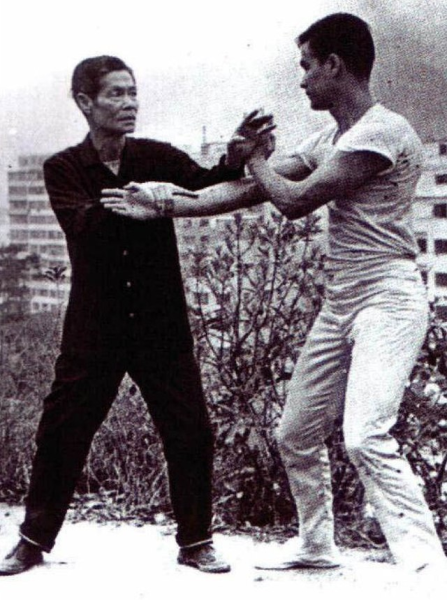

During the 1960s, young Chinese-American Bruce Lee was navigating his bicultural identity through his exploration of Chinese martial arts. While competing at a 1964 Los Angeles martial arts competition, Lee immediately caught the eyes of William Dozier, the renowned producer of Batman. At the time, Dozier was searching for an Asian actor to fulfill the role of Kato in his upcoming film, The Green Hornet.

Although the opportunity would be Lee’s Hollywood breakthrough, he was initially wary of Dozier’s offer, believing that Kato was a “typical houseboy” role that would confine him to demeaning racial stereotypes. In an interview with The Washington Post, Lee recalled that he told Dozier adamantly that he was not looking to be involved with Kato’s “pigtail and hopping around jazz.”

Despite these reservations, Lee quickly warmed up to the role once he realized that Kato was proposed to be a Kung Fu expert. Lee was ecstatic at the opportunity to showcase his martial arts skills.

Although the role of Kato did not immediately result in immense popularity, it allowed for Lee to be scouted for the lead role in The Big Boss. Produced by the Hong Kong-based film studio, Golden Harvest, the film followed the story of a righteous Chinese immigrant in 20th century Thailand, who finds himself on a thrilling crime-fighting journey against vengeful drug-lords.

The Big Boss was originally intended for Chinese audiences, but unexpectedly became a hit in the Middle East, and later Europe. Soon, overseas distributors flocked to Hong Kong, pouncing on the film’s potential, subsequently opening markets for the film in North and South America. It launched the martial arts genre into an international phenomenon, and placed Lee at its center stage. Lee commanded the attention of global audiences with his explosive physicality and captivating charisma. Immediately after The Big Boss’s release in America, the star’s wondrous fluidity and speed appeared in millions of screens as the film topped box office charts across the states.

This sparked a revolution in the American film industry, as it was the first time an Asian American was portrayed with strength and unwavering confidence. The film was a cultural milestone and began a departure from the subservient and animalistic caricatures of Asians in popular media.

The success of Lee and The Big Boss had directors across the country scrambling to produce the next martial arts blockbuster, and by mid-1973, films were releasing faster than audiences could watch. Lee continued to serve as a beacon of representation in Enter the Dragon, which shifted away from the spirituality of martial arts, instead incorporating elements of Western cinema in order to appeal to the wider American public.

As with most trends, the martial arts film craze eventually died down, but then saw a resurgence of interest in the 80s. Many low-budget films of that genre began to appear in Western media, now with Jackie Chan commanding audiences. Chan ushered in a new era of martial arts cinema, with elaborate action sequences and visually stunning choreography.

Films following themes of rivalries between martial arts schools, wisecracking heroes, supernatural powers, and the journeys of young martial arts apprentices left a bright and diverse imprint on Western cinema. Some of the most iconic martial arts films of today were produced during this time, including Karate Kid, Ip Man, and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Although the Asian-American film scene was growing, it lacked a comforting story of the realistic Asian-American experience, until The Joy Luck Club.

It’s the fall of 1993, and lines of Americans snake around New York City and Los Angeles theaters, leaving the air buzzing with anticipation. Audiences hush as projectors light up, revealing four Chinese women huddled around a Mahjong table, exchanging conversations with elegance and poise.

The Joy Luck Club was originally a novel written by Amy Tan. She writes about four Chinese immigrants, who are at face, contented Mahjong buddies. In a series of alternating perspectives between eight women, she reveals the tumultuous stories of their past, weaving them with the unraveling events of their daughters’ present lives. Within the pages of loss and grief, existential crises and tearful mother-daughter showdowns lies a gratifying story of femininity, family-ties, and changing cultures.

To the gratitude of Tan’s readers, Hong-Kong-American director Wayne Wang gracefully transferred The Joy Luck Club on-screen. In just over two hours, Wang maintains the multifaceted perspectives of all eight women, while drawing impactful parallels in between.

To the excitement of those unfamiliar with Tan’s novel, the film marked an unprecedented Asian American voice. Forget evil dragon ladies, or objectified Asian wives. Turn away from the male-dominated storylines of Kung-fu squabbles. The Joy Luck Club pioneered a refreshing counterpoint that focused on the true complexities and experiences of Chinese-American women– a rarity on American screens. “It was the first time I felt someone was writing about my life,” said Ming Na Wen about The Joy Luck Club, who plays one of the daughters.

Despite that the film underscored new beginnings for Chinese-American actors and directors, Hollywood continued to shun Chinese-American stories from the center stage.

Following The Joy Luck Club, Wang decided to broaden his horizons, pitching Asian-American films to studios. His efforts were met with no success.

The actresses of the film held new hopes for a place in the American film industry. However, their agents could not secure them any substantial roles. In fact, the four women often found themselves competing for the scarce trivial roles as fleeting characters in TV series.

Ten years after the film’s release, Lisa Lu (who played one of the Joy Luck Club mothers, An-Mei) returns to Hollywood in Crazy Rich Asians, a contemporary romantice comedy.

Cameras pan over looming animal ornaments, grand fountains of pure gold, velvet seats, meadows of three-foot tall grasses, and vintage wallpapers — a contrast from the bright luminescents, white bungalows, glass skyscrapers and sparkling waters of Marina Sands Bay.

The film follows Rachel Chu, a modest economics professor from Queens. Chu, played by Constance Wu, travels to Singapore for a wedding and meets her boyfriend’s mogul rich Singaporean family.

Within the film’s grand, sprawling symbols of wealth is, ironically, a story of immense humanity. Throughout the film, Rachel and her boyfriend, Nick’s relationship, face a series of challenges due to cultural clashes. In the New York Times, A.O. Scott describes Crazy Rich Asians as an exploration of clashes between “tradition and individualism, between the heart’s desire and familial duty, between insane wealth and prudent obedience upward mobility.”

Besides the dazzling backdrop of Singapore’s waterfronts and lavish cosmopolitan scene, the film’s grandeur is also attributed to the acclaimed cast list. It brings together Asian-American trailblazers in the various fields of entertainment — comedians Ken Jeong and Ronny Chieng, international movie star Michelle Yeoh, and hip-hop artist Awkwafina, just to name a few.

With a production budget of thirty million, and sales of almost two-hundred million, Crazy Rich Asians became the first large-scale Hollywood production without exaggerated portrayals of Asian-American stereotypes.

For many Asians across the nation, the film was a breath of fresh air, and a sign of turning tides. As Director Jon M. Chu said, “It’s not a movie, it’s a movement.”

And the movement continues.

In recent years, indie films about the Asian experience have become popularized. Within fantastical settings boasting superheroes, supernatural powers, and unexpected plot twists, lies a deeper meaning of exploration and identity.

At the 2020 Sundance festival, an indie film, Minari, was premiered. Starring The Walking Dead star and Korean-American Steven Yeun, the drama film was the timeless story of a Korean-American family who moves to a small farm in Arkansas. Set in the 1980s, it is the tender and poignant portrait of many Asian families, who struggled with assimilation and discovering their American identity.

In 2022, bolder and unabashed representation of Asian-Americans came in the form of Everything Everywhere All At Once. Its fantastical settings boasting supernatural bagels, and cosmic multi-universes served as a metaphor for the “nothingness” of life. It followed the relations between an Asian American family — mother-daughter, wife-husband — to illustrate that the only meaning of life is human connection.

The storytelling of Asian-American experiences is becoming increasingly diverse and authentic.