You’re walking down Fifth Avenue, on a day like any other. It’s the afternoon. The businessmen, dog walkers, and tourists are all out in full effect. Your mind is on autopilot, working on its own, detached from your legs moving you down the sidewalk as the urban ambiance engulfs you. In your peripheral vision is a bucket-hatted man getting closer, a few nameless strangers separating the two of you. You notice his cargo vest, but your autopilot persists. The blinding flash of his camera, inches from your face, pulls you back into reality. Your soul has been captured, and its abductor’s name is Bruce Gilden.

Gilden was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946. In the late 1960s, while he was attending Pennsylvania State University, photography was catching on throughout America. Almost everyone seemed to have a camera, either for professional use or to fulfill some sort of deeper, personal aspiration. A few notable figures in the photography scene at the time included Ansel Adams, Eve Arnold, and David Bailey. While most photographers worked with portrait photography, the practice of photographing an individual or group of people against a simplistic background, other artists focused more on the sensory response elicited by capturing the essence of an environment.

From mountain ranges to rushing rapids, most environmental photographers used secluded, naturally-formed locations as the subjects of their work. Amongst these visual storytellers were a small handful, such as Lee Friedlander and Joel Meyerowitz, who used the chaos of America’s urban landscape to evoke an entirely different kind of immersive sensory experience.

Gilden recalls his times as a young child, gazing down from his Brooklyn apartment window at the people passing along the street, seemingly oblivious to the world around them. This infatuation with the appearance of those engrossed in the routine nature of life was the catalyst for his career in street photography. After seeing the 1966 film Blow-Up, which centers around a shady fashion photographer, Bruce Gilden purchased a 35mm Leica camera. He soon began taking night classes in photography at New York City’s School of Visual Arts.

Shutterbug

His first creative undertaking was with the people of Coney Island. A recurring element in Bruce Gilden’s work is his constant search for “characters,” people with a unique or captivating look about them. It might be how they’re dressed, how their hair is done, their posture; the algorithm by which a subject allures Gilden is not predictable or consistent. It seems to be a system that works in the subconscious as if you and I are also drawn to particular people, but we lack the instruments to capture the essence of those individuals.

Gilden has a complete lack of fear when capturing that essence, which is precisely why he often finds himself in the crosshairs of both art critics and his subjects. During his first photographic outing at Coney Island, for instance, one of the men he was photographing grabbed his wrist and told him to give up his camera. Gilden, in what I assume to be a thick Brooklyn accent, promptly told the man to “take a walk.”

It isn’t Bruce Gilden’s employment of civilians as his subjects that has morphed him into a contentious figure in photography. It is instead his technique that often questions ethics in street photography and the undefined threshold of getting “too close” for the sake of art.

There is rarely an exchange of consent before a Gilden snapshot. After the intense flash of his camera, both the artist and his muse continue with the rest of their day. Sometimes, Gilden’s movements are so spontaneous that the subject doesn’t even register that their photo was taken, instead believing that Gilden was photographing the scene behind them.

This invasion of his muse’s personal space is not without creative justification. Candid photography is the practice of capturing a subject in a natural and uncurated state, a method that often makes for more meaningful photographs without any prior instruction.

Gilden’s pictures are candid photography taken to the extreme, where the embrace of an unfiltered, raw shot outweighs the importance of maintaining loosely defined ethics. The product is nothing short of captivating, as the images he produces reflect the disorderly nature of life in New York City while placing the viewer right alongside the character who caught Gilden’s attention in the first place.

In the eyes of some modern art critics, the ability to capture the authentic energy of a subject or their disordered environment does not justify Bruce Gilden’s discourteous photographic strategy or his method for deciding who is worthy of being labeled as ‘visually striking.’

In an article published by The Guardian, writer Sean O’Hagan discusses Bruce Gilden’s in-color, closeup portraits of ‘characters’ who were photographed for Postcards from America by Magnum Photos.

“Gilden may be shoving these broken faces in our faces to confront us with what we usually choose to look away from. But his style seems to work against any intention to humanize his subjects,” said O’Hagan.

Every smudge of lipstick, ingrown hair follicle, and dry spot of skin is captured in these photographs. To say that Gilden’s subjects are dehumanized by the uncompromising inclusion of all these elements which are considered ‘unpleasant’ is nothing short of ironic.

When there is a complete abandonment of the artistic tendency to buff out imperfections and present a final product that conforms to conventional beauty standards, only then is a subject humanized through the unfiltered expression of their appearance.

The traits that resonated with Gilden and made his subject a ‘character’ worthy of being captured are conveyed to the audience, allowing us all to appreciate the distinctiveness of his subject instead of being unsettled by a disconnect from our perceived sense of attractiveness. While an interesting chapter in Gilden’s career, this short-lived contention surrounding his closeup photographs is not at all indicative of the larger narratives expressed by his photography, spanning multiple decades and directing him to numerous countries across the world.

Japan’s Seedy Underbelly

Through the late 1990s, Bruce Gilden embarked to Japan multiple times with the same artistic vision that had ballooned him to success in New York City. During his time there, he focused on the unseen – the elements of a culturally rich nation that the rest of the world hesitated to delve into. Gilden’s ability to place his viewer in the middle of the captured action proved itself both powerful and unique to his artistic lens.

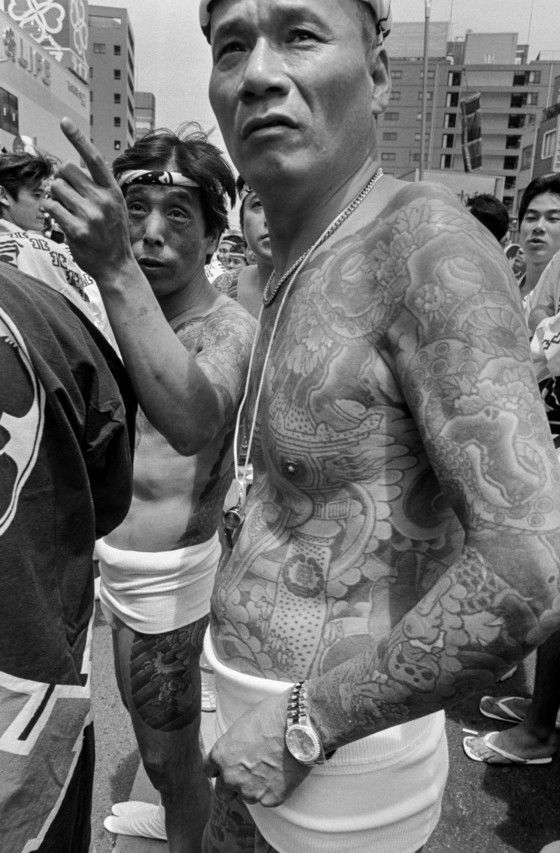

The Japanese Yakuza, characterized by their excessive tattoos and amputated fingertips, are a staple of Japan’s seedy underbelly. Much like the American mafia, they aren’t exactly known for their openness towards journalists, photographers, or anyone looking to inquire about their lifestyle.

Gilden had to build a sense of mutual respect to get close enough to capture photographs of the syndicate. He didn’t ask too many questions, nor did he want to know about the shady proceedings happening a few feet away from his camera. He did, however, stand up for himself constantly and let it be known that he wasn’t some ignorant Western shutterbug trying his hand at gonzo-journalism.

His photographs capture the Yakuza in a way that humanizes them yet alienates their customs from traditional Japanese culture. For every photograph of two mobsters sharing a laugh and a cigarette, there was a portrait of a shadowy associate fitted in dark clothing and sunglasses, concealing his true nature.

While his photographs of the Yakuza were the highlights of his time in Japan, he also snapped pictures of civilian life under the same ‘unseen’ artistic lens. From the homeless people of the early morning to the uncomfortably close quarters of the Tokyo Metro system, nothing worthy of note escaped the eye of Bruce Gilden.

Haiti in Troubled Times

Of all the journeys that Bruce Gilden embarked on in search of ‘characters’ with photographic value, none of them held the personal significance of his several trips to Haiti.

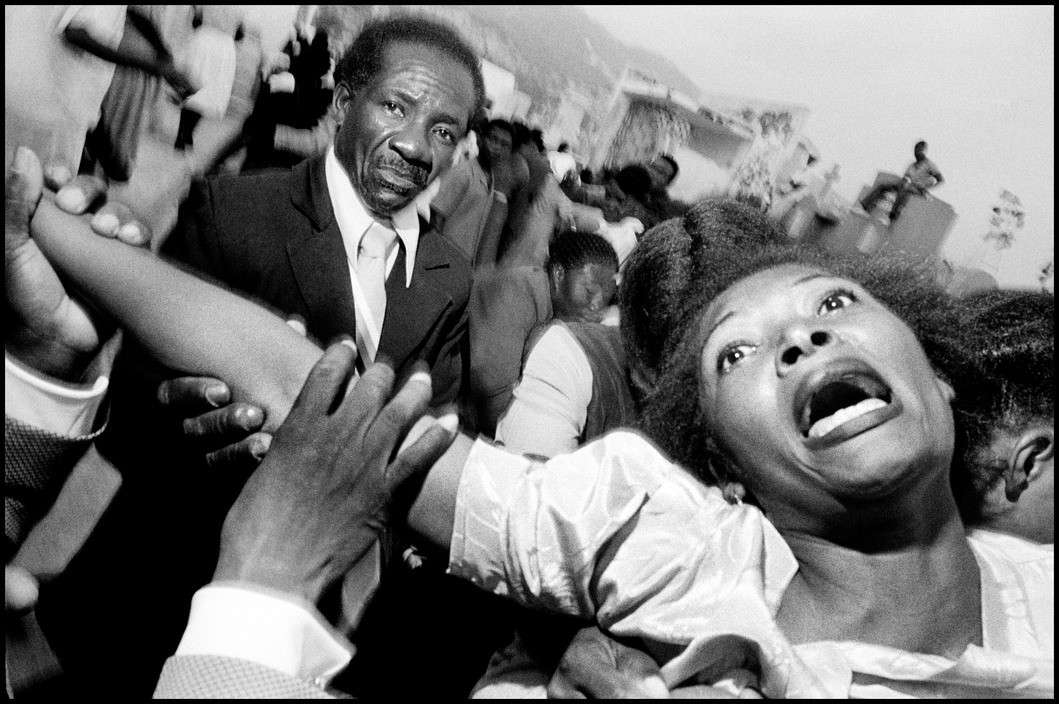

During his first trip in 1984, he took note of how the soul of the country closely resembled the New York of his childhood. The people emanated the same vibrant energy that was slowly slipping away from the urban epicenter of America. People gathered in the streets, and the dynamic interactions he captured with his camera satiated his artistic desires.

Many of his most evocative photographs originate from his time in Haiti, as it served as a kind of cultural hotspot for his creative visions. If there was nothing to be seen in the places where he was most familiar, Bruce could always rely on Haiti as an outlet for the energy he was trying to photograph.

Gilden often says that the people he captured resonated with him on a much deeper level than his role as a photographer. The soul of Haiti seemed to be a force that entwined the photographer with his unconventional subjects for over a decade.

In 2010, however, Haiti suffered a devastating 7.0 magnitude earthquake. Thousands of people were killed, injured, or displaced both during the disaster and in its aftermath. Hospitals, schools, and government buildings were reduced to rubble within just a few hours. Upon hearing the news, Gilden wanted nothing more than to return to the country and document as much as he could.

With the active emergency response throughout the country, Gilden could not arrive in Haiti until three weeks after the earthquake. The photos he captured during his stay were harrowing, depicting women and children shortly after life-changing amputations. He also documented the environmental destruction left in the wake of the calamitous natural disaster.

The Bigger Picture

Bruce Gilden has gone on record multiple times saying that of all the places he has operated during his career, there is no place harder to photograph than New York City. The people are impatient, the crowd is always changing, and there just isn’t much respect for artists who capture their subjects without expressed consent. Regardless of how he may be viewed by a portion of modern-day art critics and disconcerted citizens, the impact he’s made on the world of photography is undeniable.

He’s inspired countless artists with his visions for the raw embodiment of what makes a space, and more importantly, a subject, visually enthralling. In his own words, “If you can’t smell the street from looking at a picture of it, it’s not a street photograph.” From Japanese artist Daido Moriyama to British documentarian Martin Parr, it seems that a considerable number of artists in the photography world have, at some point, taken a page from the work of Gilden.

With decades of experience in the field and an unwavering passion for his art that remains inextinguishable even at the age of 77, who better to ask about the life and work of Bruce Gilden than the man himself? Gilden graciously consented to a Zoom interview with me. Below is our conversation.

You’ve demonstrated time and time again that as an artist in New York City and one who has traveled the world, you stick up for yourself. You stuck up for yourself at Coney Island when you were first starting as an amateur photographer, and you stuck up for yourself in Japan when you were tagging along with the Yakuza. Your ability to stand your ground when receiving backlash is very commendable, and so I have to ask: Did you always possess this assertiveness even before you began as a street photographer, or is it something that you’ve built up after decades in the field?

I’ve always had it. I remember my father was pretty tough on me, so I did the things I did because they were the opposite of what my father was doing. He didn’t play any sports so I became huge on sports as a kid. I would play against these two kids who were a year older than me because I thought I was better than them. In kindergarten, I was in a class with smaller kids, so I wondered how to get into the class with the larger ones.

I’ve always had the attitude that I can do something if I want to do it. People underestimated me in basketball so I learned how to dunk at 5’10”. I did things that were physical. I got into fights. It’s just me. I believe that I have a very strong set of principles that I live by. If I say something, I’ll back it up. I’ll help the blind person cross the street. I’ll help the person getting pickpocketed. You know, I stand up for what I believe is right.

I’m comfortable with myself, and how I act or react. I don’t care what people think – that’s their problem. Of course, you want everyone to think highly of you, but I deal with what’s in front of me. I was discussing this the other day with my dentist. Her aunt or something, who’s an oncologist – my dentist said ‘She’s so cold.’ You have to be cold because people’s lives are on the line. Same with photography because I have to get the pictures I have to get, so I need to be a certain way.

Are you familiar with the idea of Sonder? It is defined as the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own — populated with their ambitions, friends, routines, and worries. Now that you can place a name to this feeling that we’ve all felt at some point, do you think Sonder plays a significant role in the subjects you choose to photograph?

No. I can give you a resounding no. To me, I look at people like they’re in a movie, and I’m the director. For example, in Italy, sometimes I saw someone who was interesting and they had a cigarette in their hand. I’m thinking ‘It would be better if they raised the cigarette to their face in a certain fashion.’ And I’d wait. And if they didn’t do it correctly I’d always mumble to myself ‘Oh, they didn’t take direction.’ To me, it’s mostly a visual and the feeling you are emitting. That’s what’s important to me.

If you put me in a room with a hundred tough guys, there might be only two that I want to photograph because they speak to me visually. If you’re in the lowest position of power of all the hundred, I’ll pick up on that. When I’m taking a portrait, it requires more direction sometimes. My assistant told me to look at where the person was when I started taking the portrait and where they were by the end.

I want to touch on your time in Haiti briefly. You’ve said that it’s your favorite country and that its spirit is irreplaceable, as even New York doesn’t hold the same artistic significance. What kind of traits do the “characters” of Haiti convey that make them so compelling to you, and how did those traits change after the 2010 earthquake?

Well, of course, I go down there and I look for what interests me visually. For example, Médecins Sans Frontières let me into one of their places where they were taking care of people. I went down three weeks after the first earthquake and I remember I needed an operation at the time, but I still went to Haiti because I felt I wanted to be there.

So I was there, and I remember seeing this beautiful young girl in her early twenties. She had just lost her leg and she was still smiling, and I cried.

In Haiti, I couldn’t be a loose cannon about it. I asked permission for a lot of things and there was a line that I didn’t cross. But still, it was all about visuals to me. Maybe don’t call me a bleeding heart.

Through an interpreter, I asked if I could take a portrait and they said yes. You know, I have a soul inside me which most people don’t. I think my photography is learned but it’s not learned by going to school. Everything that I choose to photograph has been part of me since I was a kid. I liked the strangest wrestler, I wanted to play the drums, these are me, whereas someone like Diane Arbus had a personal curiosity.

This is all coming from my guts. I couldn’t do anything else, you know? One of the older photographers from Magnum told me ‘Come on, Bruce. You should do flowers.’ I can’t do flowers, okay?

Years ago I read a statement about photography – when I was your age – and it said ‘People who photograph with love can do it their whole career. People who photograph with passion can only do it for a short time.’ But I find passion in my photographs. It’s what keeps me alive. It’s something I do for myself, and it’s very important to me.

You’ve gone on record a handful of times saying that New York has lost its “soul.” There are fewer characters out in the city, and the people have lost the aura that once made them such compelling subjects. When you consider how the city has changed since you began photography, what do you think are the specific factors which have sucked the individuality out of the population?

It’s the whole world that’s changed. The same thing happened to Naples. I went in 1969, and I went back earlier this month. In the poor quarters, people dress like they would in New York, their hair looks like the rest of the world. Overall, I think people are becoming more similar.

People are less courageous today. They’re afraid to go against the grain, and I think they will pay for that. They’re going to get taken for all they’ve got. You have to have courage in life, you know? If something bothers you, you’re inclined to say something. And don’t just say something, do something. Anyone can say anything these days, but doing something is what matters.

Do you, Bruce Gilden, believe that we the people of New York City, photographers or not, should make a more conscious effort to appreciate and acknowledge the characters surrounding us?

That’s an individual statement. For example, I read a lot but I have a lot of trouble with poetry. I can’t relate to dictums of ‘you need to do this’ or ‘you need to do that.’ Everybody is their own person. I do think people should make an effort, but I don’t think people should be told what to do. There are people who are leaders and there are people who are victims. I don’t think you can really change who you are deep down in your soul, but you can try to go to the positive and stay away from the negative.

I tell myself that all the time, and sometimes I don’t listen. But for the major things, I listen. Even when I started photography, a customer at my father’s gas station was the night editor for UPI, United Press International. They offered me a job emptying waste paper baskets so I could learn how to be a photographer.

And I said to them ‘Wait a second. I’m not taking that job.’ I guess if you stretch it, being around photographers and the equipment could teach you a thing or two, but that’s not my mentality. If you’re going out, then I’m going out too.

Hey, by the way, you said you go to Bronx Science, right?

Yes.

Do you guys still get snowballs thrown at you by the kids over at Clinton?

“Years ago I read a statement about photography – when I was your age – and it said ‘People who photograph with love can do it their whole career. People who photograph with passion can only do it for a short time.’ But I find passion in my photographs. It’s what keeps me alive. It’s something I do for myself, and it’s very important to me,” said Bruce Gilden.