Born in 1911, Peter Birkhäuser was a Swiss visionary painter whose vast portfolio of artistic work unmask the uncanny otherness of the unconscious psyche. Early in life, his childhood was overshadowed by the death of his mother, but even as a child he decided he wanted to be a painter. His early encounter with a medieval picture of a knight in armor in a Basel art gallery had fascinated him so much that he thought to himself: “I must become a painter. I want to learn to paint knights like that.”

Birkhäuser studied art under the Basel artist Niklaus Stoecklin, who was known for his prominent role in the Magic Realism art movement of the 1930s and 40s. The art movement was a reaction to the conflict between reality and abnormality stemming from Western culture’s dissociation from mythology. It often blurred the line between reality and fantasy in this respect. Later in Birkhäuser’s life, traces of the Magic Realism would find themselves in his work.

But for the next two decades, Birkhäuser’s artistic work received general approval. Birkhauser reproduced what he saw in nature and human beings with as much technical and aesthetic skill as he could apply. Birkhauser sought to follow the example of the old masters, rejecting contemporary modern art because it seemed to him to be empty and have a merely destructive function.

But one evening, while he was working in his studio, a moth fluttered and settled against the windowpane. Birkhäuser later turned this incident into a painting in which the moth appears to be of monstrous proportions with a wingspan reaching up to several yards. Whether he knew it at that moment, the moth incident would go on to shape Birkhäuser’s lifelong struggle. He interpreted this picture years later as a representation of his own state of mind. The moth, a reflection of his soul, was prevented by the glass from reaching the light, a metaphor for his consciousness. Birkhäuser realized he had grown up in a rationalistic and agnostic environment, and his instincts were all against the unconscious and the religious.

The problems the moth painting presented had involuntarily developed into a midlife crisis in Birkhäuser’s life when he was about thirty. He lost his old enthusiasm for his artwork. Painting required more and more effort. His attachment to the traditions of art was a source of deep vexation to him. Pieces stood around for long periods half-finished, and completing them only brought feelings of disgust. Working produced a sense of impotence, and Birkhäuser suffered more and more from frequent fits of depression.

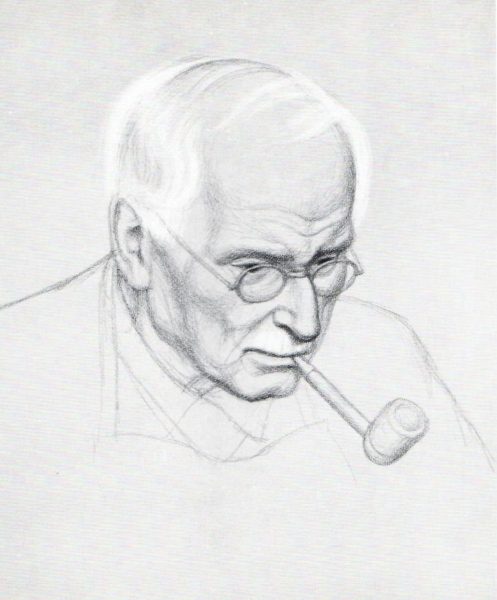

It was in this state of art-blockage that Birkhäuser and his wife, Sibylle, came upon the ideas of Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, a renowned psychoanalyst who lived in Zürich. An outstanding student, friend, and rival of Freud, Jung is often cited as one of the foremost proponents of analytic psychology, and especially well-versed in the field of dream analysis. Jung has drawn up such elusive ideas as the collective unconscious, a repository of ancient primal symbols known as the archetypes hidden deep inside the mind and common to all humankind through our shared ancestral memory. Such a powerful idea would have its effect on the course of Birkhäuser’s life.

Impressed by Jung’s analysis, Birkhäuser and Sibylle began to note and analyze their dreams. Birkhäuser and his wife entered analysis with Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz and developed a friendship with Jung himself. Soon after, it became clear that the creative side of Birkhäuser’s personality demanded a quest for a new spiritual value. Over the course of 35 years, Birkhäuser kept notes on over 3,400 of his dreams, and his work increasingly focused on the images emerging from his unconscious. This new development in his work was not well-received by the art community of the time, but viewed today, his vivid paintings bear striking testament to the disruptive and transformative reality of individuation. It reflects the purpose of Jungian psychology, which is to seek wholeness of personality by bringing the unconscious contents into reality.

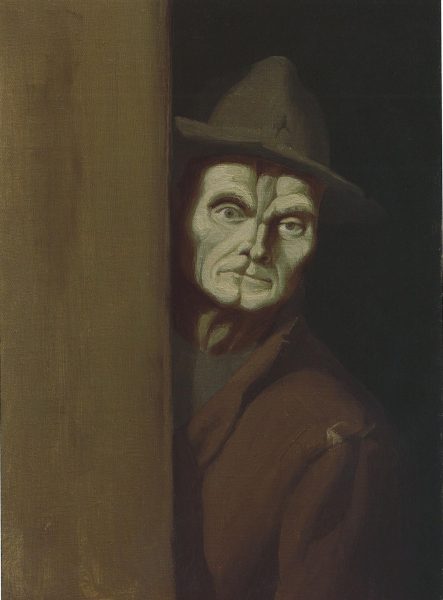

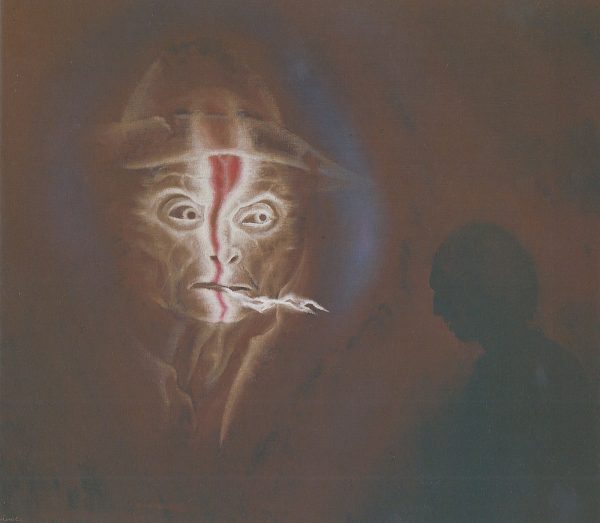

The World’s Wound (1953)

In 1953, Birkhäuser painted ‘The World’s Wound.’ In rage and despair he smudged the picture onto the canvas with no faith that anything reasonable would come out. He had been haunted by the face in his dreams for four years and felt that this painting of a split man was in no sense a product of his conscious will.

In his dream, this man was desperately trying to reach Birkhäuser. He personifies the tragic inner split of the modern man, who, through an over-reliance on rationality, has lost his spiritual and inner meaning. We can no longer overcome this split, but we can become conscious of it. Then the creative spirit of the unconscious could be reintegrated with our consciousness. The eye on the left is opened in fearful vision, while the right eye remains skeptical and cool.

It was after this encounter that Birkhäuser was compelled to give up painting motifs of his own choice and devote himself to representing the sufferings of our age as reflected in the collective unconscious.

Unfortunately, Birkhäuser’s new and bizarre paintings were met with blank incomprehension. Because of this, he was unable to support himself from his art and was forced to earn his living from advertising work. His wife, his most loyal and constructive critic, died suddenly in 1971. That year, Birkhäuser saw the beginning of a serious lung problem and increasing physical handicaps. However, the last five years of his life were accompanied by striking progress in his spiritual development and artistic productivity. He devoted himself exclusively to bringing these unconscious images into reality.

Just how hard this struggle with himself must have been is affirmed by the fact that it took the artist twelve years to make the great leap and paint a picture entirely according to his own imagination, with no model from the real world.

Birkhäuser’s fantasy pictures reflect not only the artist’s own personal psychological situation, but also the spirit of the age, revealing what is taking place in the depths of the collective unconscious in all of the people of our time. Because of this, they are not easy to decipher; they are simply there, and wish to be experienced.

He stated that, “This mysterious power has its own will and ends. It knows things that no human being could know. So I’m sure it would not be wrong to give it the name of God. It is after all greater than every human faculty. It is what we impute to God, to know the future, or to know what an individual should do in the decades ahead.”

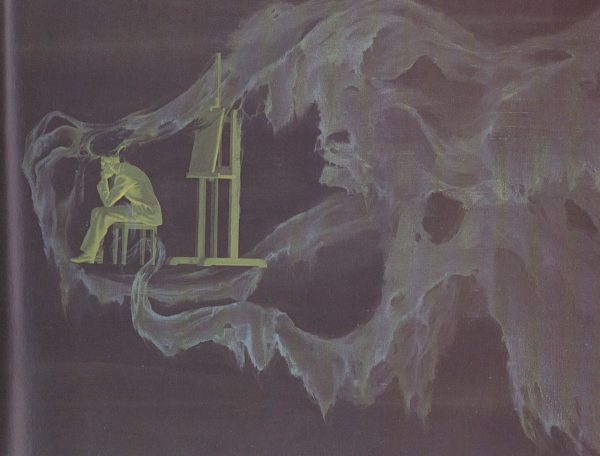

Depression (1954-1955)

Every new creation is preceded by an annihilation of the previously held conscious views. Everything has become stale and meaningless, and the unknown psychic realm reaches out to grasp us with tentacles like mist, liquid, or ectoplasm. Depression dissolves the head of the painter, as he sits idly with his back to the easel, suspended in space, with nothing solid beneath his feet. Only by turning round to face the uncanny powers can he discover their secret intentions.

Fire Gives Birth (1959-1960)

Here in the sea of flames is what appears to be the mythological Godhead, which gives birth to all the colorful and wondrous forms and shapes of nature. The content is breaking out from the hot fires of libido, one could also say from the waves of emotion and excited feeling. It is creative energy. Out of it we finally emerge into the suffering and beauty of life.

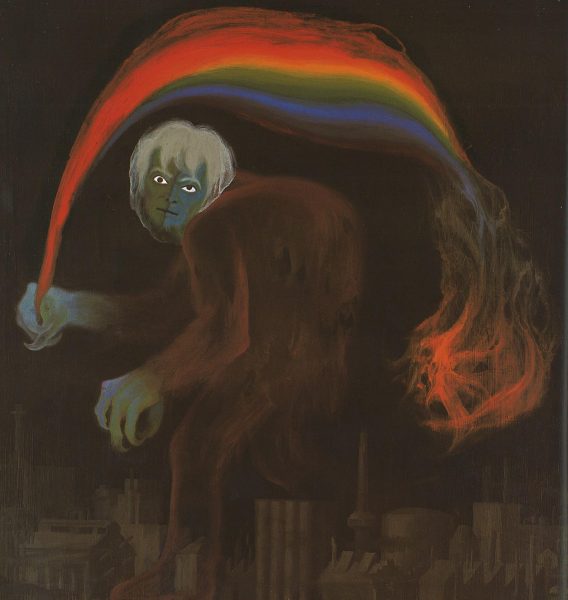

The Outcast (1960)

From the gray monotony and functional technology of our industrialized towns, the spirit of the soul, the creative secret of nature, is banished. With heavy steps, the creature retreats towards the left, into the unconscious. He trails behind him a tail of flames, which is also a rainbow. The latter hints that reconciliation with God is still possible, but the fire could destroy all our towns. The face of this outcast spirit is halved, like the man with ‘The World’s Wound.’

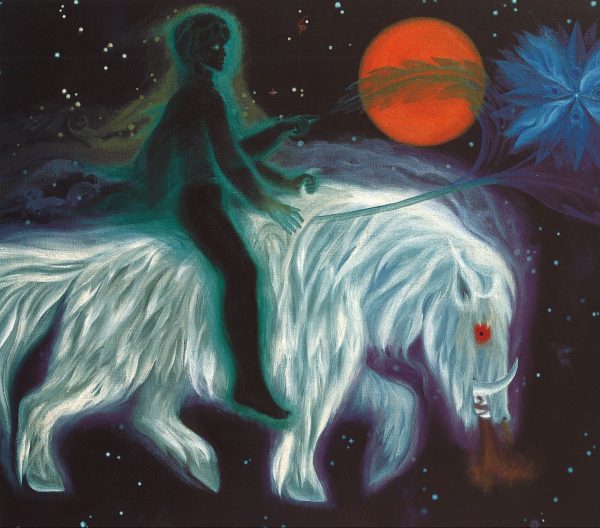

Puer (1960)

Puer aeternus means eternal youth. This is the boy-god predicted in Revelation as the child who was snatched up to heaven. He is the complete man of the future. Wherever he stretches his hands, new life begins to bloom.

This painting appears in Carl Jung’s book Man and His Symbols and symbolizes the Self, which appears not as a superior wise old person but as a marvelous youth. He sits on a white boar-like horse who moves through the dark heavens. He is silhouetted because of his nocturnal or unconscious origin.

The round object like a sun behind the youth is a symbol of totality and the boy’s four arms recall other “fourfold” symbols that characterize psychological wholeness. Before the boy’s hands hovers a flower – as if he needs only to raise his hands and a magical flower will appear.

The Magic Fish (1961)

The two youths are united as the fish swims down and to the left, where they may bring a new meaning from the depths of the unconscious. The future world savior is personified in his double form and remains hidden inside the fish in the depths of the sea, the mortal and the immortal hold each other in a close embrace.

The fish’s eye is like a flower – Eearth’s answer to the light of the sun. Above it all is the eye of God, a huge blue eye that suggests that something in the cosmic background “sees” everything.

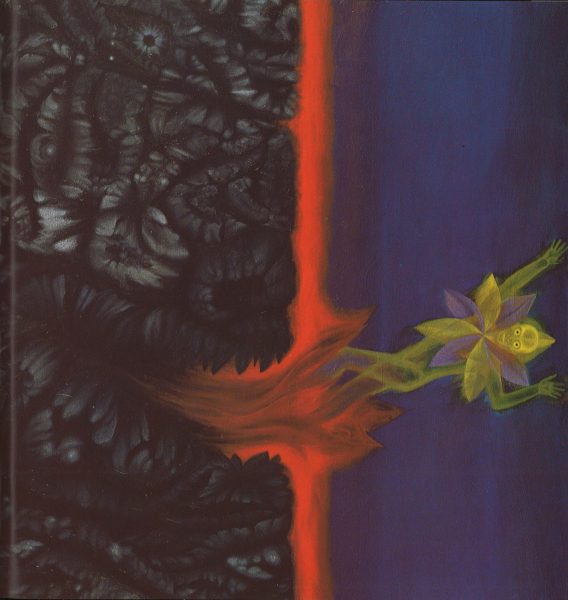

A Birth (1961)

Out of what looks like a mass of intestines or brain folds, a transparent man-like being is born, not onto the earth, but into free space. This being emerges out of the collective unconscious, the layers of the psyche far removed from consciousness (the collective unconscious). He is simultaneously an eight-petalled flower, which symbolizes psychic totality, like the ‘golden flower’ of the alchemists and Taoists. It is the image of the resurrection of the inner being, the image of the Self, the wholeness towards which we all strive.

Alarm (Date unknown)

A terrified and frustrated woman beats on the door in alarm, but if she would only turn around, she would see the symbols of wholeness which are behind her, which could restore the balance in her life.

Untitled “The Four-Eyed Anima” (Date Unknown)

This painting is reproduced in Carl Jung’s book Man and His Symbols. A negative anima appears as an overwhelming, terrifying vision. The mood of the anima moods can sap the life of a man, his whole life takes on a sad and oppressive aspect. The four eyes have a symbolic meaning, as the quaternity (a group of four things or people) contains the possibility of achieving wholeness. By integrating one’s anima, one gets closer to individuation.

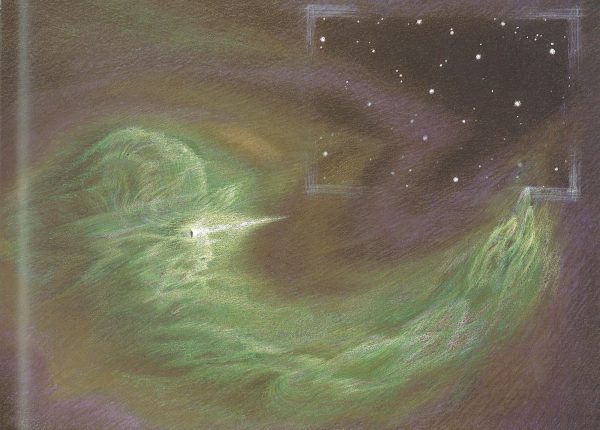

Window on Eternity (1970)

There is that within us that frees us from too narrow a view of reality. The decisive question for a person is: are we related to something infinite or not? That is the telling question of one’s life. If we feel and understand that here in this life we already have a link with the infinite, desires and attitudes change.

Whoever opens his soul to the divine receives the revivifying experience of a higher world order. A “window on eternity” opens up. The artist has himself become part of this spirit, for it uses the hand of a mortal man in order to reveal its mysterious cosmic constellations.

Sun of the Night (1970)

A nocturnal, owl-like creature with uncanny eyes rises from the horizon like the moon. Its look seems somehow foreboding, as if it were in possession of a remote knowledge that certainly surpasses human consciousness. Its strangeness and even eeriness make clear that the encounter of the individual with the spirit of the unconscious is not a comfortable task.

On the contrary, the human being in his small house seems to be completely and utterly at the mercy of that supreme and alien power of the “Other.” Compared to the powerful Sun of the Night, the small house with its warm human light appears rather unimportant. And now this dwelling place offers a vessel to the human, that is, a protected place of shelter. The human being needs such a place, in order to listen to the objective psyche, to the spirit of the unconscious.

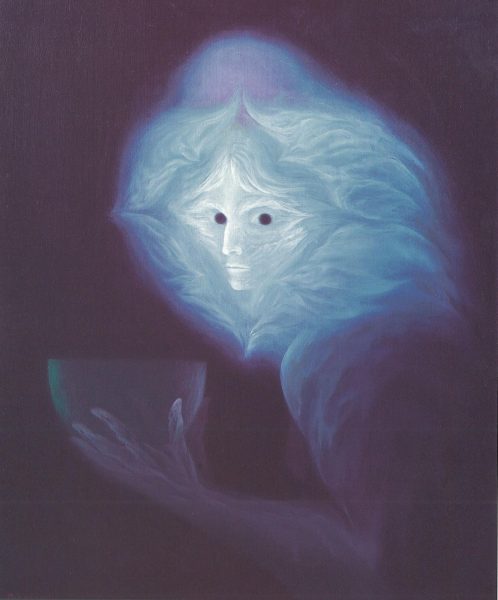

The Woman with the Cup (1971)

Birkhäuser did not understand this painting after he had completed it, but its meaning became apparent when his wife, Sibylle, died a few months after he had painted it. This woman is a visitor from the beyond, and she encourages us to live life with meaning each day. The ‘white lady’ is popularly considered a harbinger of death (thus the darkened eyes) and she brings the cup of suffering and transformation. The delicate vessel is reminiscent of the Grail which provides truth and spiritual nourishment. The whole ghostly figure seems to be outside the colorful realm of life.

24 of March 1971 (1971)

This is the date of the unexpected and sudden death of Birkhäuser’s wife. Although the whole framework of life (the house) has been shattered by the lightning, a suggestion lies beyond: what appears to be senseless and accidental is in fact the work of a cosmic force with human characteristics. In other words, Birkhäuser conveys that meaning could after all be found in such a tragedy.

Lighting the Torch (1974)

The creative person experiences the divine grace of being allowed to light his small torch at the fire of the Creator. Birkhäuser once dreamed that he was given this grace. The animal face in the fire in the form of an eight-petalled flower signifies enlightenment and order in chaos.

Having Speech (1975)

The split man of ‘The World’s Wound’ has been transformed by the artist’s experience of the unconscious and by following its inspiration. Blood flows into the scar so that it can heal. The eyes look in the same direction and the man, formerly a despairing mute, now begins to speak.

Spiritus Naturae (1976)

Birkhäuser often dreamed of wild cats and the aura of power shining from them. They represent the instincts, but they also have a spirit of their own, a way of seeing things in the light of the unconscious psyche. Birkhäuser’s artistic eye could ‘project’ inner experiences in this way, and he was able to see the reality of the psyche.

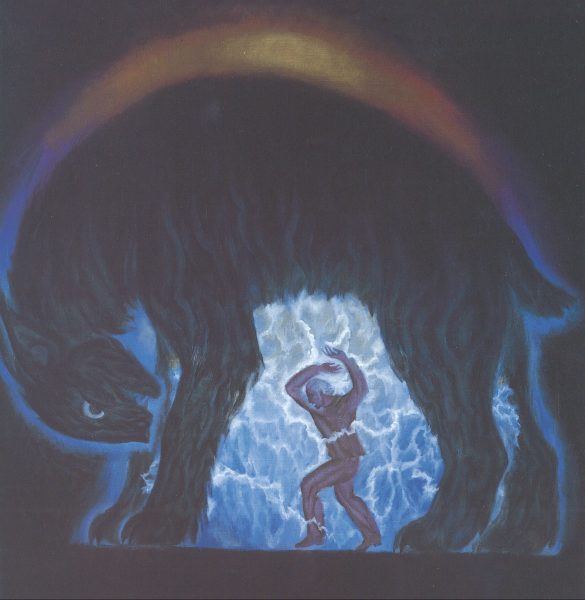

Lynx (1976)

This is Birkhäuser’s last finished painting, created shortly before his death at the age of 65 on November 22nd, 1976. In his hospital bed, he was surrounded by electric sparks and feared that he would not escape.

The creative artist serves a spirit of nature which tries to manifest itself through him. But sometimes its enormous energy is too much for him, especially when the body becomes older. The frail human being has to surrender to the powerful god. The lynx is a far-sighted creature which can see in the dark. Its name is related to “lux” (light).

Through his confrontation with the unconscious, Peter Birkhäuser dedicated his whole life to showing us that no matter what, we can find light from the darkness. The solitary light emanating and glowing from the deepest depths of the darkness is what makes it a truly remarkable source of light. For it is this inner inextinguishable fire of life that guides us out of the darkness.