Edith Hamilton, the world renowned classicist and expert in mythology, once described great art as “the expression of a solution of the conflict between the demands of the world without and that within.” Those conflicts are both trivial and monumental. Some tables wobble. Some chairs creak. Some days are good. Some aren’t. In the big picture, however, these momentary inconveniences make little difference. Others make a bigger one. Such is the case of war. When the world uncurls its fists and Ares ignites his blazing sword, the beautiful chaos and awe-inspiring horror breeds creativity and unparalleled expression.

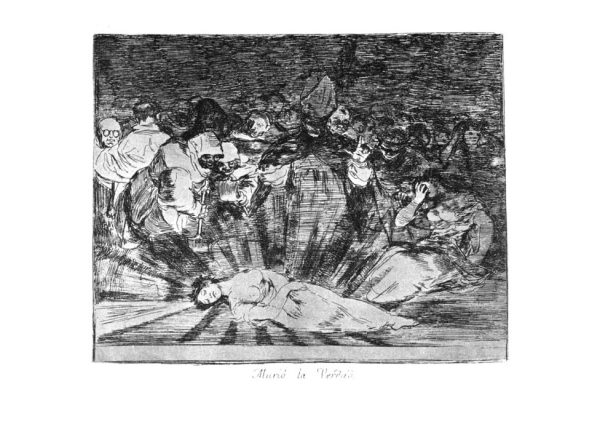

Art is a mirror to a moment in time; each piece reflects and captures the values and character of its period. In the late eighteenth century, Francisco Goya constructed a collection of aquatint prints entitled The Disasters of War. Among them is a sketch of a woman encompassed by darkness. Below her lies a simple caption: “truth has died.” Through this piece, Goya depicts how the casualties of war extend beyond people. Contemporary musical compositions like Zombie by The Cranberries further convey this relationship between conflict and art. The song operates as an anthemic indictment of violence in Northern Ireland, the group’s homeland.

Among these media, however, poetry remains the most subjective and varied form of war-time expression. Several literary critics will cite certain pieces as being quintessential to this sub-genre. Within the vastly explored realm of war-time poetry, the works inspired by the First World War are numerous. The broad spectrum of poets who cultivated this art form are explored below.

Lauded as one of the genre’s finest, Wilfred Owen serves as the first case study of war-time poetry. Born in Wales, Owen enlisted in 1915 and joined British forces deployed in the French trenches. To cope with the horrifying realities around him, Owen wrote – and wrote a lot. He composed several poems during this time, featuring themes of death, destruction, and misplaced nationalism.

Dulce et decorum est is perhaps his most-well-known. The title is a Greek expression, meaning “it is fitting and proper to die for one’s country,” originally written by Horace, a Roman poet. The phrase, featured in Odes, was a rousing declaration, one that celebrates and glorifies the act of military service. Owen’s interpretation of conflict differs entirely. In fact, the title represents the central irony within the poem: soldiers suffer inconsolable pain for nothing while officials inspire jingoism.

Owen takes the audience on a panoramic journey around the battlefield, showcasing the horrors of fighting through the “white eyes writhing with skin,” and “blood [that] come[s] gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs.” Using gory sensory detail, Owen elucidates the absolute atrocity and destruction fostered by war. Yet, he concludes with the same adage:

“My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.”

Owen advises against getting caught up in the message of patriotism, realizing both sides are the same; the soldier suffers no matter the color of their uniform, and death in the name of country brings nothing but more death. Owen’s scathing rebuke of nationalist sentiment serves as the foremost example of war breeding timeless creative expression.

Owen’s portfolio does not end with his most prominent work, either. The themes displayed throughout Dulce et decorum est present themselves across his literature. For example, Anthem for Doomed Youth replaces the ringing of passing-bells during funerals with the “stuttering rifles’ rapid fire.” He also refers to the casualties of the war as “cattle.” Owen similarly laments the absence of humanity featured both on the battlefield and at home. Beyond the recurring horrors of war, Owen ridicules the government bureaucracy, implying that, to the powerful authority, soldiers are nothing but numbers, pawns on a chessboard, cattle herded to their untimely demise. Arms and the Boy provides another instance where Owen invoked ancient poetry, as his title references Virgil’s opening lines in The Aeneid. Given the poem’s focus on a boy not dissimilar to Owen himself, the breadth of his work pertaining to war corrupting youth expanded.

Spring Offensive portrays a landscape, a beautiful countryside in France, ravaged by the bloodshed and gore of conflict. Not only does Owen juxtapose the surroundings with the war, but he seemingly makes the country analogous to man. Both are corrupted. Both are bloodied. Both were vital. Now both are muddied.

Perhaps the most respected poem of the period, In Flanders Fields, further contrasts a serene, quiet landscape with the inevitable death brought on by the war. John McCrae describes the surrounding field, a burial ground full of crosses, as a beautiful terrain, with larks singing and poppies growing.

He takes the perspective of the fallen, encouraging the living to take the torch from the dead and carry on the fight. The purpose he conveys contrasts Owen’s belief tremendously. Either way, neither would live to see their work revered, as both were killed in action before war’s end. McCrae hardly glorifies the war, but he introduces the same idea Lincoln did in Gettysburg around sixty years prior: the dead shall not have died in vain. Or, as he puts it:

“Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.”

Owen might have a deep bibliography, but, as highlighted by McCrae’s work, he is just one war-time poet with one lens. Owen’s perspective as a front-line soldier, though, contrasts several other writers of the time. Among the most prolific works in this genre is Laurence Binyon’s For the Fallen. Where Owen rebukes the nationalist establishment, one that treats its soldiers like pawns and rooks, Binyon recognizes their heroism in a different light.

As an Oxford graduate with acclaim prior to the First World War, Binyon’s success and age ensured he never saw service. However, inspired by the tremendous casualties, he took to pen and paper to commemorate the dead. He wrote:

“There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.”

Throughout the poem, Binyon asserts that “we will remember them,” ensuring the soldiers’ deaths will not be in vain for they were “fallen in the cause of free.” He classifies the servicemen as noble and righteous, worthy of acclaim and respect. Ironically, Owen, the soldier of the two, felt as though the fighters were taken advantage of and naive. To him, there is no honor in dying on the battlefield; to Binyon, though, that fate is one for the ages.

Where Binyon glorifies the dead, lifting them up on a pedestal for society to praise, another British soldier, Charles Hamilton Sorley, takes an approach closer to Owen’s. Sorley’s When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead is far from a ringing endorsement of war.

Sorley, like Owen, witnessed the casualties up close, and clearly, that informed his writing. In his sonnet, Sorley portrays the dead not as martyrs or inspirations, but as silent, “deaf,” and “blind.” Sorley criticizes those who give posthumous, disingenuous praise to the fallen, proclaiming that the deaf know not their praise and the blind see not their grief. Baked within his impassioned statement is a reflection on the contradiction of service, one Owen explored as well: the dead are respected while the living are ignored. Sorley encourages people not to glorify the untimely, horrific killings of the war with superfluous language. Instead, he suggests a matter-of-fact approach to recognizing the fallen. He was not ashamed of his service; it was a necessary reaction to the circumstances around him.

He grew irritated at those that sentimentalized their deaths as grandiose sacrifices. That language was unproductive and self-aggrandizing, implying a monumental undertaking and responsibility that never really existed. The war gave Sorley a stark realization: death is just that – death.

“‘Say only this, “They are dead.’ Then add thereto,

‘Yet many a better one has died before.’”

Even in denigrating the casualties of war as insignificant, Sorley still recognized the unity of conflict, a sentiment expressed in To Germany. Looking across to his enemy, he shares their pain, and further conveys his discontent with fighting. As he puts it, “the blind fight the blind.” War is nothing short of misguided, and people fight aimlessly not for themselves, but for others’ interests. The pointlessness of war makes the loss all the more painful.

Yet, Sorley understood the brotherhood, from comrades to enemies, that the trenches facilitated. He hoped to look back fondly: “We’ll grasp firm hands and laugh at the old pain.” He realized the futility in that too, though. For as he instructed: “until peace, the storm, the darkness and the thunder and the rain.” Sorley’s perspective is informed for better or worse by war, as he balanced the destruction around him with the shared humanity of it all.

Owen also saw the common condition amongst soldiers. His poem Strange Meeting depicts the interaction between two soldiers who quickly realize they are in Hell. One recognizes the other as his killer, yet all is forgiven in the end, as Owen expressed:

“I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now”

Owen steeped the bond in darkness, as the horrors of war have permanently stained their existences. Still, they are together in this strife. One of Owen’s most prolific quotes, “I am the enemy you killed my friend,” embodies that very notion. In the commotion and chaos, the mud where inhumanity thrives and brutality blossoms – the lost souls of conflict reunite in brotherhood.

For many soldiers, poetry serves as the reaction to the world around them, many of whom leave behind works that outlive them. Part of the tragedy lies beyond the message. Wilfred Owen was killed in action in 1918; Sorley in 1915. War cut short their lives, rendering their brains thoughtless and yet, inspired their brilliance, giving them a platform to express their true ideas.

I could further glorify the talents of Owen and Sorley, but they would not want that. Instead, to quote the latter, “they are dead, yet many a better one has died before.” According to Sorley, “it is easy to be dead,” and they did not want honor.

They deserve it, however. Therein lies the horrors of war, that mutilates spirit, crushes dreams, confuses actions. These creations exist only as byproducts of shellshock, leftover remains of mines and wounds, fallen friends and family. Pain is one of life’s givens. Not in the quantity or scope experienced during war, but still, it is a constant – a unifier among loosely connected individuals. The likes of Sorley and Owen channeled their suffering into art, art that has survived long beyond themselves. In a world of short memories, their words echo through the speeches of international leaders, commemorate the dead at memorials, and immortalize what it means to fight.

It’s easy to paint in just two colors: to highlight the black and white, the good and bad, the Allied and Central Powers, the saved and the damned. What’s harder is to find the collective strife, the unifying struggle of war.

Conflict is inherently alienating. Owen pointed his gun at scared, young German soldiers; many of them just wanted to get home too. The poetry of the First World War, by contrast, is no battle in the trenches. Reconciling the futility of the war and cultivating it to give voices to those on the field – that is a proud legacy.

Maybe it seems out of place in this discussion of harrowing stories and lives cut short, but the Red Hot Chili Peppers put it best: “destruction leads to a very rough road, but it also breeds creation.”

For many soldiers, poetry serves as the reaction to the world around them, many of whom leave behind works that outlive them. Part of the tragedy lies beyond the message. Wilfred Owen was killed in action in 1918; Sorley in 1915. War cut short their lives, rendering their brains thoughtless and yet, inspired their brilliance, giving them a platform to express their true ideas.