Ridley Scott’s recent film Napoleon is a massive historical epic based on the military career of France’s early 18th century Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte. Although acclaimed by American critics, the movie was controversial at best in the country where the movie’s star built his famous Empire, France.

The French themselves, or at least their film critics, responded the most negatively to Napoleon’s release. While English and American reviews applauded the epic cinematography and stunning set design, French critics lambasted the film’s historical inaccuracies, mediocre plot, and most of all, its unflattering illustration of a national hero.

Such disparities seem to demonstrate the cultural animosities between these nations rather than their taste in cinema.

In France, a country steadfastly proud of its history, Napoleon is an immensely popular figure in both culture and politics. In a recent poll, almost 75% of the population in France maintained that Napoleon’s actions were beneficial to the country, a percentage that has almost doubled since 1969.

Traces of Napoleon’s influence adorn Paris and proudly display his accomplishments. The Arc de Triomphe pays homage to his decisive victory in the Battle of Austerlitz while the Hôtel des Invalides – the building that houses his imperial tomb – towers over the streets.

Napoleon is so deeply enshrined in French culture, that any attempt to Anglicize or condemn his life and legacy was unsurprisingly met with criticism. The left-wing daily newspaper, Libération, scorned the biopic as ‘clumsy’ and ‘unworthy of Napoleon’s person and legacy.’

A critic in the prominent French paper, Le Monde, wrote, “Directed by a Briton who has long reigned over Hollywood, Napoleon is a film that essentially reminds us that the Empire has changed hands since Waterloo.” The author’s claim, that America’s Hollywood now runs the world’s culture, can be observed in Napoleon’s English viewpoint along with choices for actors and filming locations.

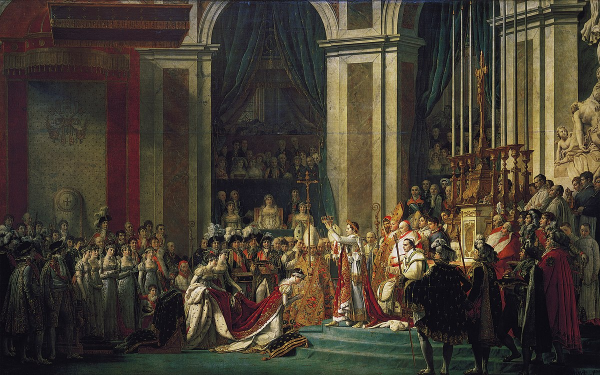

The casting and filming decisions support an English perspective, as almost all of the movie was shot in England. Classic scenes from French history, such as the Coup of 18 Brumaire, were reenacted under a background of English architecture. The Lincoln Cathedral in Lincolnshire took the place of Paris’ Notre Dame as the stage for Napoleon’s coronation.

Napoleon himself is played by Joaquin Phoenix, an American actor with an American accent. Empress Josephine, Napoleon’s brother Lucien, and Chief Foreign Diplomat Tallyrand are all played by actors from the United Kingdom. The clipped dialogue of Napoleon in the film mirrors more the manners of the 18th-century British upper crust than the flamboyant rhetoric so common in the French language, both past and present. To American audiences, this would be as if a film on the American Revolution cast a George Washington with a guttural French accent, using French expressions and mannerisms. “Sacré bleu!”

The presentation of the Napoleonic empire, succeeding the French Revolution betrays a similar English perspective. The film opens with the barbarity of the First Republic, defined by the blood-thirsty guillotine. A slow-motion montage brings Marie Antoinette to her fall from regal grace as jubilant, singing crowds pelted the soon-to-be-executed Queen with rotten vegetables. Napoleon watches (although the real historical figure did not actually witness the execution), silently and resolutely condemning the Revolution’s anarchy, akin to how the British elites of the time viewed the First French Republic.

For the remainder of the film, Ridley Scott’s Napoleon Bonaparte represents far more the British perspective of a war-mongering Corsican ruffian than the French vision of the Emperor as a regal and just statesman. Critics in the paper, Le Monde, point to the film’s emphasis on battles at the expense of political and administrative reform.

Napoleon is a controversial figure. Through different modern cultures and perspectives, the French Emperor is seen in antithetical views, as a war-hungry dictator or a political and military mastermind. The former is the image most popular in England and America, while the latter is the predominant French conservative perspective.

Napoleon has become a staple figure of French far-right politics. The former emperor’s legacy has come under attack due to his warmongering and colonization, as well as his racist and misogynistic policies – under Napoleon’s rule slavery was reinstated, and women’s rights suffered. Yet, such condemnations seem to have bolstered the importance of his regime to French Conservatives.

Again, the French fear of and disdain towards Americanization shines through. Many consider criticisms of Napoleon to be an importation of American revisionism. Valeurs Actuelles, a far-right magazine, christened Napoleon, “The Anti-Woke Emperor.”

By showing only the battle and love scenes of the Emperor’s life, Ridley Scott’s Napoleon fails to illustrate either perspective of Napoleon, whether as a cruel dictator or as a deliverer of political glory and stability.

Napoleon’s lycée school system, legal code, and centralized bank allowed for a stable and meritocratic world following the destabilizing French Revolution.

However, he also reinstated slavery after the First French Republic abolished it. Napoleon fought to oppress a slave rebellion in Haiti and discriminated against prominent Black generals. The Emperor also rescinded many of the Republic’s achievements towards women’s rights. The Napoleonic Code forbade women from entering into legal contracts and gave husbands total ownership over a woman’s property.

Many historians critical of Napoleon point to the Empire as a betrayal of the republican ideals established by the French Revolution. The Emperor acted like a dictator, making almost all decisions himself, rarely consulting an elected body of representatives. He re-wrote constitutions at will to consolidate power in the hands of one person – himself. Napoleon also operated a secret policing program to quiet dissent and eliminate political opponents.

Napoleon does not represent either of these sides. In the film, the Emperor is neither a hero nor a villain, but a sad and grumpy joke. From Scott’s perspective, he’s a hot-headed, war-loving general and a puppet actor in a doomed romance drama.

The expedition to Egypt is a perfect example of the film’s inadequate middle ground. The movie does not present the expedition as enlightened, showing the myriad of scientists that Napoleon brought, or as horrific, with devastation from battles and the unforgiving heat which left thousands dead from disease, wounds, and dehydration. Instead, the war-loving General blows up a couple of pyramids (which never actually happened) and then returns home to deal with his soap-opera love life.

A common criticism that many French critics share is that the biopic slips up on specific historical facts, such as inaccuracies with Marie-Antoinette’s long hair or the depth of the pond in the Battle of Austerlitz. Yet, it is not the minute historical inaccuracies that hurt the film, but rather the incomplete portrait of Napoleon himself and his empire.

Missing from the biopic was Napoleon’s administrative legacy and his impact on French history, both positive and negative. The movie ignores the Emperor’s success in establishing a clear and long lasting-legal code, advancements in religious tolerance, and huge leaps toward equality for Jews in French territory. In addition, the film fails to incorporate the oppressive backwardness of Napoleon’s Empire, his efforts to curb women’s rights and abolition, as well as the immense destruction of his wars. The Napoleonic Wars are often listed in the top twelve deadliest conflicts in human history.

The task attempted by Ridley Scott’s biopic is immense and the movie’s mixed reviews are understandable. Napoleon is a multi-layered, contradictory historical figure, impossible to jam into a two and a half hour movie. The runtime is simply insufficient in illustrating the complexities of a historical figure as controversial as Napoleon Bonaparte. The desire to abandon the political administration of the Emperor or his iron-fisted rule is strong, especially when attempting to create a narrative that is supposed to entertain more than educate.

Still, the movie’s plot left many non-history expert reviewers confused and wishing for more. The biopic follows a rapid joint story of Napoleon’s military career and the soap opera of his love life. Jumping back and forth between battles without much context, the film left some viewers bored and unable to follow the plot.

The scenes that divide each epic battle do little to set up the next fight. Napoleon is told to capture Tulon from the British, to invade Egypt, and to overthrow the government, and then he wins at Austerlitz and loses in Russia. After the fires in Moscow, we see a few soldiers shivering, after which the former Emperor is forced into exile. What separates these impactful and tumultuous years is only the drama of Napoleon’s love life.

What the film executes best are its epic battle sequences. Whether in the naval city of Tulon, the frosted forests of Austerliz, or the rainy terrain of Waterloo, Napoleon shines as a cinematic masterpiece.

The increasing dependence on CGI in cinema makes Ridley Scott’s reliance on actual human stunt work a breath of fresh air. The battles feel both immense in magnitude and tangible, pages of history brought to life by the choreography and set design.

In the Battle of Austerlitz, the camera pans to the fallen soldiers underneath the surface of the lake, adding meaningful, dramatic effect during the heart of the battle. A wide view of the Allied Coalition in the Battle of Waterloo shows thousands of soldiers aligned in rigid formation, accurately depicting the order and complexity of the historical battlefield.

The costumes and set design similarly transport the audience into the heart of Napoleonic France. The vivid detail and flourish of the clothing bring out the characters and their stories. Napoleon himself is most recognizable by this tricorn hat – in the film, he seldom never takes it off.

Ultimately, Ridley Scott’s Napoleon is just one perspective on the life of an immensely controversial and multi-dimensional man. It makes for an epic movie, with thrilling battle sequences, but if you’re watching to learn more about the tumultuous and vastly interesting French Empire, read a book or listen to a podcast.

To watch Ridley Scott’s Napoleon (rental fee required) on Amazon Prime, click HERE.

A critic in the prominent French paper, Le Monde, wrote, “Directed by a Briton who has long reigned over Hollywood, Napoleon is a film that essentially reminds us that the Empire has changed hands since Waterloo.”