The Metropolitan Art Museum, commonly known as the MET, is one of the world’s largest art museums, with 5,000 years of world history on display. The MET is a global institution, centering on art from every part of the world, from the Aztecs to the Uzbeks. Many of their exhibitions are focused on exploring cultures and nations often ignored by art history.

This is where the MET’s aptly-named exhibition ‘Africa & Byzantium’ comes in. According to Andrea Achi, the associate curator of Byzantine art, “The exhibition builds upon a long legacy of Byzantine exhibitions at the MET and it connects North Africa and the Byzantine world between the fourth to the fifteenth century.” The Byzantine Empire has been recognized for its contribution to art history, but its interactions with Africa have not been put under the spotlight properly, until now, relating to the eurocentrism of most art museums.

North Africa was first under the rule of the Romans, and when the Roman Empire fell, the region was conquered by the Vandals. North Africa was then reconquered by Emperor Justinian I. Under Byzantine rule, churches were renovated and strategic sites were fortified. The locals, however, opposed Byzantine attempts to enforce Orthodoxy upon them. In 698 A.D., Arabs finally put an end to Byzantine reign. Not only were parts of Africa, specifically North Africa, under the dominion of Constantinople, but many other African countries, such as Ethiopia, Tunisia, Egypt, and Sudan (Nubia), had rich trade with the empire, exchanging arts and beliefs.

The exhibition is divided into three major parts. The first is “Africa in Late Antiquity,” which displays art from the fourth to seventh century. This is followed by “Bright as the Sun,” covering Africa after Byzantium, displaying art from the eighth to sixteenth century. Finally, there’s “Legacies,” with art from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries.

The last part of the exhibit, “Legacies,” addresses the impact that the Byzantine Empire left on the region. Despite the empire falling in the fifteenth century, its impact throughout Africa was still felt, and it is still present today.

Entering the exhibition, you are greeted with gold lettering over black walls entitled “Africa & Byzantium.” Directly under that gold lettering is the first piece of artwork, a ‘Mosaic Panel with Preparations of Feast.’ This second-century Roman mosaic exemplifies the diversity of the Roman world: all of the men depicted are very different in skin color and hair texture, but they were all part of one empire.

Further into the exhibition, “Africa in Late Antiquity” starts, and art from Byzantine Egypt makes an appearance. In a tour of the exhibit, the exhibit’s curator Andrea Achi said, “Egypt was one of the most important provinces of Byzantium. Cities such as Alexandria, and artistic production centers along the Nile valley produced some of the best textiles, jewelry, wine, and oil of the entire Byzantine world.”

Much of the Ancient Egyptian art in this section is heavily influenced not only by the Byzantines, but by the Romans and Greeks as well. The Byzantine Empire was a continuation of the legacy of the Roman Empire. There is a textile fragment depicting Artemis with another figure, presumed to be the ancient Theban hero Actaeon. There is also a box with two gods, Isis-Tyche-Aphrodite and Dionysus-Serapis, an example of syncretism. The box is beautifully carved with the syncretized goddess wearing the horns of Isis and a calathos. There are other examples of Ancient Egyptian art being inspired by Greek and Roman aesthetics throughout the exhibit.

There are several sculptures from a Coptic, Egyptian Christians, monastery in Saqqar that have acanthus leaves carved on them. In Greek, Roman, and Mediterranean architecture, the acanthus represents enduring life and immortality. In Christianity, however, the leaves represent pain, sin and punishment. These sculptures show clear influence from the Byzantines, as this style was very popular in the sixth century.

Today, Egypt is a Muslim-majority country, but centuries ago, it was the cultural hub for Christianity. There was also a time where there was a significant Jewish population in Egypt as well. Around the second century, there was a transition from ancient Egyptian religion to Coptic Christianity, which still retained certain Ancient Egyptian traditions, such as mummification.

One of the oldest and most important Christian monasteries in the world was built in Egypt during the sixth century, Saint Catherine’s Monastery. It was a very important symbol for the Byzantines, as Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora heavily invested in the monastery, fortifying and donating enormous bounties of art.

The ‘Icon with the Virgin and Child, Saints, Angels, and the Hand of God,’ one of the donated art pieces, is one of the oldest surviving icons in the world, having been cast in the sixth century. It displays the Virgin Mary holding Jesus, flanked by Saint Theodore and Saint George in the foreground. At the top, there are two angels looking upwards. This painting presents iconography that is present all throughout the Christian world. The two Saints are surrounded by halos of light and hold crosses. In the following centuries, his painting inspired many other works from Constantinople to Ethiopia.

This section of the exhibition introduces the theme of cultural interconnectedness, with different cultures interacting and adopting different aspects from each other. There’s also the introduction of Tunisian art traveling throughout the Roman Empire. This exhibition emphasizes connection, and its first part perfectly sets that up.

In the second part of the exhibition, “Bright as the Sun: Africa after Byzantium,” there is the continuous theme of interconnectedness. It was during this time that the Byzantine Empire lost control of the southern Mediterranean region. Despite that, the Christian communities of North and East Africa continued to trade with the empire.

The art of the Copts, Ethiopians, Nubians, and Byzantines show clear unity. In a statue depiction of the Virgin Hodegetria, images where the Virgin Mary is guiding the viewer towards Jesus, the statue is made out of African elephant ivory. There is also Bishop Petros with Saint Peter the Apostle which combines the traditional Byzantine style with Nubian Saints.

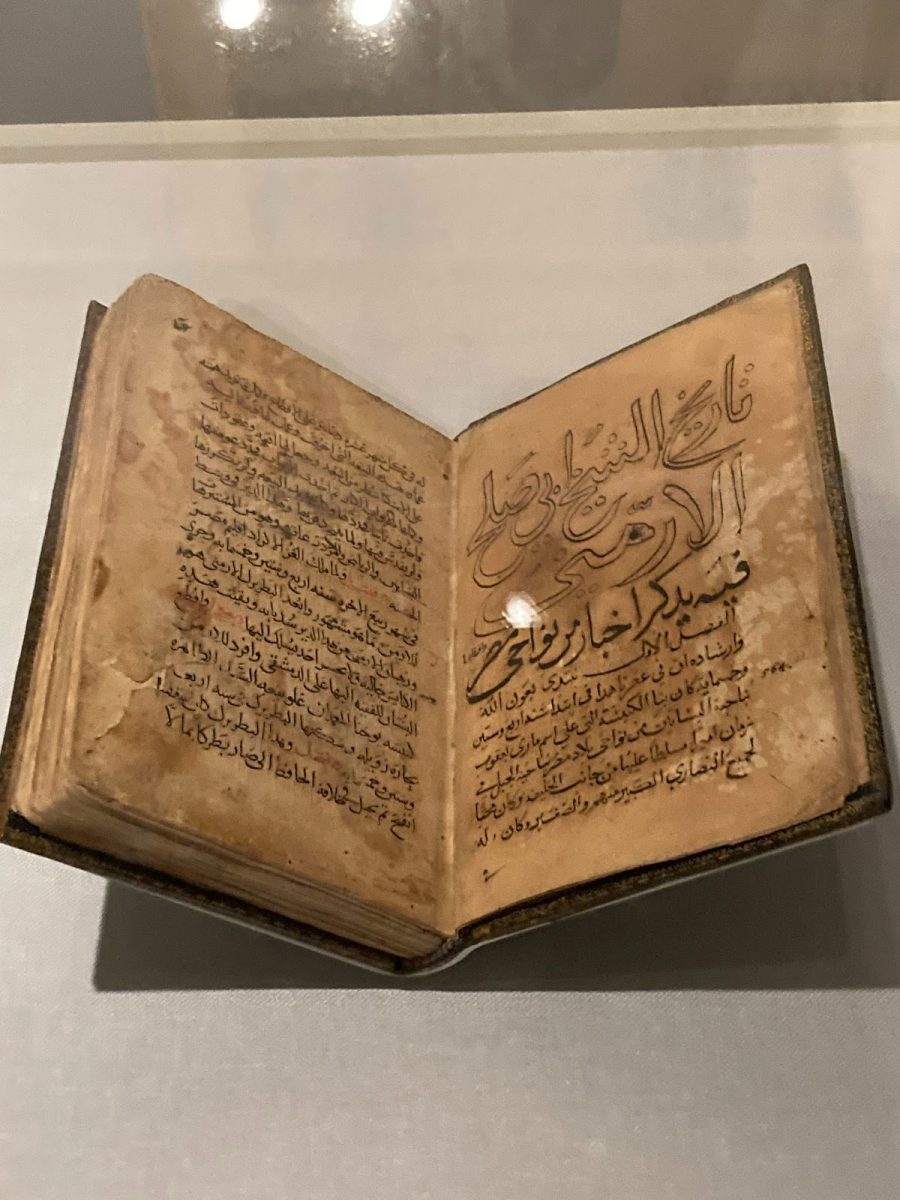

In this part of the exhibition, there are more pieces of writing. Not only are there Bibles with the Coptic script, there are also documents using Old Nubian, and gospel manuscripts in Ge’ez, an ancient language that originated in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. While these communities frequently interacted with each other, the exhibition stresses their differences as well. All of these documents and scripts look wildly dissimilar, with Coptic resembling Greek and Latin and Ge’ez resembling Tigre and Tigrinya.

While all of these communities were inspired by Byzantine art, the art that resulted is not the same. The Nubians frequently placed their own religious figures in paintings and used characteristic dull colors. The Copts used more color than the Nubians, and incorporated more iconography like the Virgin Hodegetria. Ethiopians utilized the most color out of all the cultures, all the while staying very close to Byzantine aesthetics.

The third section entitled “Legacies,” concludes the exhibition. While the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453, its influence did not die, as Byzantine-style art continued to thrive in many African-Christian communities, such as in Ethiopia. Many of the icons seen earlier in the exhibition remain visible, like the Virgin Hodegetria. The iconography from this era remains similar to the iconography of the previous centuries.

After showcasing art from after the fifteenth century, contemporary pieces are shown. Tsedaye Makonnen, an Ethiopian-American artist, created light-filled totems to honor black women who have suffered violence, whether that violence is from attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe, or from crossing the border to get to the United States. Each segment of the light sculptures are named for 50 black women who have died, either through police brutality, or by crossing the Mediterranean Sea. On each of the boxes is a Coptic cross. Today, in Ethiopia and Eritrea, such crosses are commonly used to protect against harm. Even now, the Byzantine Empire continues to inspire modern artists.

‘Africa & Byzantium’ is incredibly important to art history. The art historical discipline has frequently highlighted interactions between the Byzantines and Western Europe but falls short in exploring Byzantine interactions with Africa. Over the centuries, Africa has been home to some of the oldest Christian countries in the world, and it has accumulated a rich history with the Byzantine Empire that should not be overlooked. The MET Museum’s exhibition ‘Africa & Byzantium’ stands as an important corrective, and it is on view through Sunday, March 3rd, 2024.

‘Africa & Byzantium’ is incredibly important to art history. The art historical discipline has frequently highlighted interactions between the Byzantines and Western Europe but falls short in exploring Byzantine interactions with Africa.