Debonair men, cherubim babies, and a merry Santa Claus. The subjects in Joseph Christian “J.C.” Leyendecker’s art came in many different forms, but the recognizable hatchwork and smooth curves used to construct them ran true throughout his work.

His distinct style of painting was what drew The Saturday Evening Post, Cluett Peabody & Company, Collier’s, and various other high-profile clientele to commission J.C in the early twentieth century. Whether on the cover of The Post or in various everyday advertisements, Leyendecker’s art permeated the world of American consumerism with masterfully crafted illustrations.

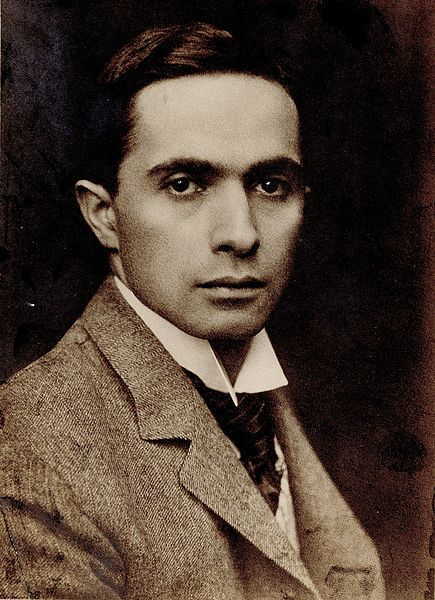

Leyendecker was born on March 23rd, 1874 in Montabaur, Germany to Peter and Elizabeth Leyendecker. He had three siblings: his sister Mary Augusta and his two brothers Francis Xavier and Adolph. When Leyendecker was eight years old, the family moved to Chicago, Illinois.

Leyendecker, along with his brother Frank, began to pick up art, and later started to apprentice at the engraving house of J. Manz & Company as a teenager. There, he soon became an Associate Illustrator while studying at the Chicago Art Institute with Frank.

In early 1896, 19-year-old Leyendecker received his first commission: 60 illustrations for a client’s private Bible. That same year, the brothers left for Paris to attend the Académie Julian, a private painting and sculpting school. After two years in France, J.C. and Frank moved back to Chicago to open a studio, where J.C. started his decades-long relationships with Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post, two prominent American weekly magazines.

Due to incredible advancements in color printing technology, the first two decades of the twentieth century were considered ‘The Golden Age of American Illustration,’ and J.C. Leyendecker was at the forefront. In his covers for The Saturday Evening Post, he painted expressive characters with such a degree of skill that Norman Rockwell, one of the most famous illustrators for The Post, cited him as his muse and later mentor, writing “I began working for The Saturday Evening Post in 1916 and Leyendecker was my god.”

In 1900, the Leyendecker brothers moved their firm to New York City, where J.C. began to work on promotional art for Cluett Peabody & Company, a men’s clothing manufacturer. Some of his most notable commercial illustrations are of fashionable men with chiseled jawlines and muscular physiques — the esteemed “Arrow Collar Man” — found in the shirts and detachable shirt collar advertisements for Cluett Peabody.

The attractive depictions of this trade character not only drew in customers seeking to emulate the style and charisma of the well-dressed men in the illustrations, but also admirers of the illustrated men. The national appeal of the Arrow Collar Man increased the company’s sales to $32 million a year, topping the charts as the most successful men’s clothing companies in the U.S. at the time.

Leyendecker’s art continues to captivate audiences in contemporary times. The New-York Historical Society held an exhibition featuring Leyendecker’s work, Under Cover: J.C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity, this summer from May 5th to August 13th, 2023, focusing on the homoerotic undertones in his art. When I met with him for an interview, Donald Albrecht, a guest curator for the show, explained how they wanted to take a slightly unconventional approach in viewing Leyendecker’s work, one connecting his portrayals of the male identity with his own sexual orientation.

“Because [the exhibition] was modestly sized, we felt it was important to focus on one aspect of Leyendecker’s work. If you just do a Wikipedia study of it, his career was enormous. I mean he worked in both advertising and editorial; he did calendars, he did books, magazines. He just did an enormous amount. So what we did was, we focused on his imagery of men. Because in 1913, The Sun newspaper praises his capacity to depict men, and we thought that was an interesting theme, because he was a gay man, his model was his romantic partner, they were together for almost fifty years, and he was his primary model — a man by the name of Charles Beach.”

Beach, a Canadian fan of Leyendecker, met the artist in 1901 and later served as the blueprint for many of the men in many of Leyendecker’s illustrations, including the Arrow Collar Man. “What you do when you do exhibitions is you look at the material that is available, and you try to bring out the narrative, the story you’re trying to convey. That’s what a curator does; a curator is sort of a midwife who’s taking material and bringing it to the public and explaining certain aspects of it,” Albrecht added.

Having done several exhibitions on New York City queer life before the Under Cover, including one called Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York at the Museum of the City of New York, Albrecht had experience in portraying gay life in museum exhibitions. He divided the Leyendecker show into two themes: the first focusing the male body and the second being male behavior and interaction.

The exhibition layout was designed with a purpose. As Leyendecker’s paintings lined the walls of the exhibition, other artifacts such as newspapers, magazines, and films, took their places in plexiglass vitrines. “We contextualized the paintings to tell various stories,” Albrecht said.

Since Leyendecker’s work mainly focused on an idealized white male image, the exhibition curators took to filling in the gaps of the twentieth century’s first three decades. To highlight underrepresented subjects in Leyendecker’s work, Albrecht noted that the exhibition specifically chose to include artifacts from movements during the time period, such as the Harlem Renaissance.

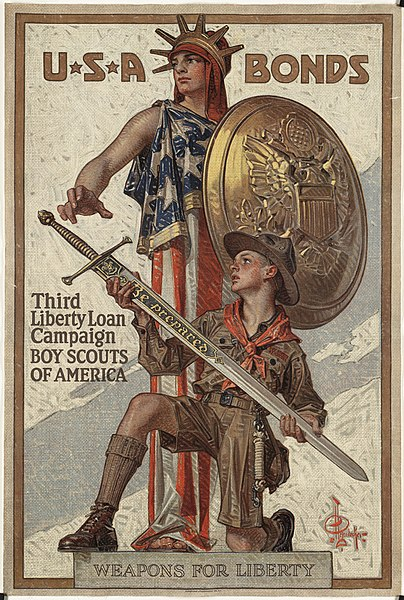

They used juxtaposition in this way three times throughout the show. “We took the football player and the pilgrim (one of his covers for The Saturday Evening Post), and we talked about the obsession with football and the Ivy League in the case. We took the Harlem Renaissance and compared it to Leyendecker’s depiction of tuxedoed, well dressed men. And then we took his World War I soldier imagery (from his illustrations supporting the war effort) and juxtaposed it with a magazine called The Masses, which was a communist anti-WWI magazine that showed what war was really like — how it destroyed the body — whereas in the case of Leyendecker, it was all very heroic…One of [the covers for The Masses] was a cartoon of a skeleton measuring a soldier and there are caskets behind, and the caption is a pun: ‘Physically fit.’… He’s being fit for these caskets.”

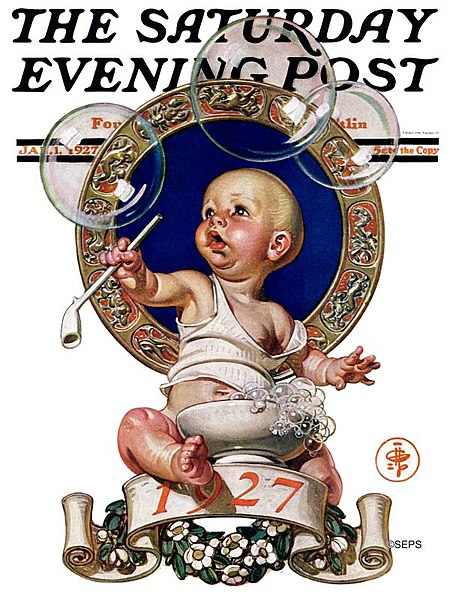

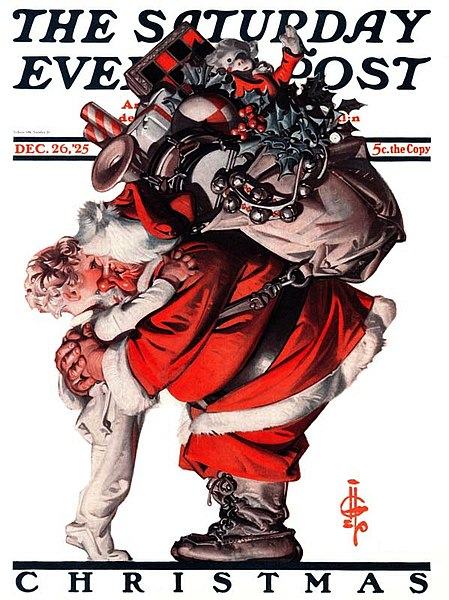

That isn’t to discredit Leyendecker’s range of artistry, however. Among other subjects, he painted babies, daily life, athletes, and war heroes, producing countless memorable scenes of wonder, beauty, solemnity, rage, and humor. Leyendecker held a special grasp on what people wanted to see, whether it was handsome men in style for B. Kuppenheimer & Co. or children enjoying cereal for Kellogg’s.

Settled in his fourteen-room mansion with separate studios and a garden since moving to New York, Leyendecker lived with his partner Charles Beach, his brother Frank, and his sister Mary. Eventually, in the early 1920s, Frank moved out of the house, thought to be a result of his jealousy of his brother’s fame. Frank died of an overdose in 1924.

With editorial changes at The Post, Leyendecker’s relationship of forty-four years with the magazine ended in 1945. He began to live more solitarily, enjoying his life away from the public eye. When he died from a heart attack on July 25, 1951, he left a $60,400 inheritance to his sister Mary and to his partner Charles Beach. Leyendecker’s patronage had been declining; of the five attendees at Leyendecker’s funeral, Norman Rockwell, an avid supporter and friend of Leyendecker, served as one of the pallbearers.

Although Leyendecker’s life came to an end in 1945, his legacy lives on. His innovative use of graphically appealing illustrations for commercial use, like for the Arrow Collar shirts, had not only inspired artists like Norman Rockwell, but also helped lay the groundwork for the contemporary use of storytelling in promotional work. While advertisements before the 1920s often emphasized the specifications of a product, Leyendecker’s work highlighted the role it could play.

The Arrow Collar Man he created for Cluett Peabody represented many people’s idealized figure of a man. The New Year’s Baby he painted for The Saturday Evening Post was a pudgy depiction of childhood innocence, as well as the lovable character on almost forty of the magazine’s New Year’s covers. The jolly Santa Claus he drew for The Post’s Christmas covers served as an iconic rendition of the holiday, with his particular Santa dominating the list of “The Best Santas Ever,” a cover collection that The Post made to feature some of its favorite covers of the red-robed figure.

Through his multitude of subjects, Leyendecker conveyed emotion in a way that was captivating, resonating then and now with viewers of his work. As Albrecht put it, “He created the kind of advertising we have today that tells stories, one that is evocative and emotional.”

In his covers for The Saturday Evening Post, Joseph Christian “J.C.” Leyendecker painted expressive characters with such a degree of skill that Norman Rockwell, one of the most famous illustrators for The Post, cited him as his muse and later mentor, writing “I began working for The Saturday Evening Post in 1916 and Leyendecker was my god.”