Nestled in the Robert Lehman Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art lies a gallery of blazing hues, beckoning visitors to immerse themselves in the dynamic world of Fauvist art. Initially opened on Friday, October 13th, 2023 and on view through Sunday, January 21st, 2024, Vertigo of Color is a beautiful encapsulation of Fauvism, the fleeting yet contentious art movement infamous for sparking artistic wrath and change at an unprecedented scale. Displaying works from two pioneers of the Fauvist movement, Henri Matisse and André Derain, ‘Vertigo of Color’ invites visitors to witness the audacious use of media that both captivated and scandalized the art world.

The Fauvist movement began in the same way it ended, with artistic outrage. In 1904, a group of young artists shattered the constraints of traditional art, gearing away from realism and towards the uncharted territory of abstraction. The French media sprung to crush the new movement with criticism, condemning it as the “Fauvist movement” and its artists as “Les Fauves,” which is the English equivalent of “wild beasts.” However, this condemnation did not deter the movement. Rather, these young artists embraced their new title with pride, turning the backlash they faced into creative fuel. By the time the Fauvist movement concluded a mere four years later in 1909, it had wreaked havoc on the French art community, leaving it in a mixed state of frazzled confusion and excitement.

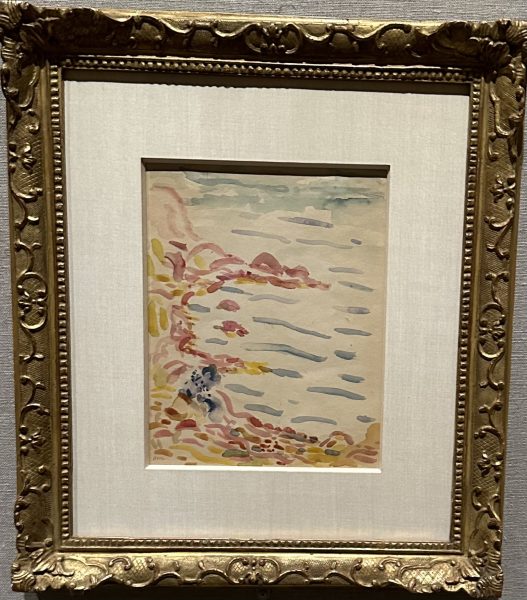

The true scandal of Fauvism was its frivolous use of color. To Fauvists, choosing colors was a matter of aesthetics as opposed to accuracy. In other words, grass could be painted neon pink if the artist came to the consensus that it was the ideal shade to collaborate with the other components of the piece. Fauvists calculated composition with a level of precision that people don’t often appreciate, placing each color meticulously to form the kaleidoscope of hues best suited to the eye. The striking and chaotic nature of fauvist works invokes a unique array of emotions that remain unmatched by any other art in its medium.

Although “The Fauves” consisted of many loosely associated artists, such as Albert Marquet, Georges Rouault, and Maurice Vlaminck, ‘Vertigo of Color’ embraces the approach of condensing Fauvism, narrowing its focus to the accepted faces of the era, Henri Matisse and André Derain. Yet, the exhibit manages to further articulate its themes by boiling down the artists’ works to those they produced in Collioure, France. This region, located in Southern France, appears to be the artistic influence of virtually all the works showcased in the exhibit. However, this is with good reason: Collioure is the birthplace of Mattise and Derain’s Fauvism adventure.

In the early summer of 1905, Matisse invited fellow artist Derain on a venture to the French Mediterranean to explore novel artistic styles and influences. The two artists found themselves in a small yet charming fishing village, known as Collioure. Upon briefly exploring the town and observing its beaches, ports, and mountains, Matisse and Derain were immediately enchanted by Colliure’s classic natural scenery. The sites in Collioure, although seemingly plain, were perfectly tailored to the artists’ surreal creative vision. Ultimately, Matisse and Derain would use these simple views as the inspiration for the set of aberrant and alluring paintings presented in ‘Vertigo of Color.’

Collioure was not the sole artistic influence that Mattise and Derain shared. Matisse’s wife Amélie, oddly enough, modeled for both Matisse and Derain. Amélie did not model merely on occasion. On the contrary, she was the focal point of dozens of pieces. Her prevalence in the two Fauvists’ works is a prime example of the undoubtedly intriguing nature of the relationship between Matisse and Derain. Amélie is the third pillar of Matisse and Derain’s art with which ‘Vertigo of Color’ places a pointed emphasis. To the right of the entrance is an entire wall decorated with paintings picturing Amélie, with others scattered throughout the exhibit.

Amélie did not model in a traditional sense; in many of the works in which she appears, it is challenging to even distinguish her figure. Matisse and Derain often chose to have her silhouette fade into the background, meshing seamlessly with the surrounding brush strokes. Matisse’s ‘La Japonaise Beside Water, Collioure’ characterizes Amélie’s crouching figure with nothing but a few diluted navy brushstrokes, allowing her to dissolve into the coastline. Her presence is subtle but certainly felt, exerting an inexplicable gravitational pull that captivates the viewer’s gaze.

Traversing the exhibit ‘Vertigo of Color,’ I sought to discover the emotions that Fauvist pieces stirred in their viewers, independent of the scenes, figures, or objects they featured. “[The colors] invoke feelings of happiness, of distraction. Frankly, I could live in a world with these colors. They’re colorful and happy as opposed to what we see in current art. The art we see now is either a political statement or a symbol of distress, but when I look at art I want to escape. These paintings allow me to escape into a beautiful world,” said Judy, a visitor at the exhibition. “The paintings carry a lot of energy, sort of a playful take on reality,” said Rebecca, another visitor.

After interviewing multiple visitors, I was left with a diverse range of responses, all of them complex and intriguing, but drastically different. “Depending upon your ability to see, the colors will affect you differently. I guarantee that if you asked this question to 10 different people, they would give ten different interpretations,” said James, the final visitor with whom I conversed, providing me with the lucidity I had been seeking.

The beauty of Fauvism lies in its ability to affect every individual differently. Fauvists were not seeking to illustrate one rigid narrative with their works, having let go of the expectation that their pieces would instill a fixed set of emotions. Instead, Fauvists sought to paint simple moments with no apparent importance in a manner that made them striking, leveraging the mundane as their ultimate inspiration. “These paintings are glimpses into people’s lives,” said Ms. Fraser, a Fauvism enthusiast who was visiting ‘Vertigo of Color.’ In a dim reality, Fauvists achieved the seemingly impossible feat of finding brightness simply by appreciating the monotonous acts of life.

Even the location of the exhibit in the Lehman Wing of The MET itself is quite dull. With bare gray walls, grainy carpet, and pale lighting, the lower level of the Lehman Wing is certainly not a spectacular sight. Despite this, wandering through the exhibit, you cannot help but consider the space bursting with life and zest. It seems that the paintings on the walls, even those as small as a piece of printer paper, act as beacons of light.

Given the infamously frenzied aesthetic of Fauvism, it is coincidental that the majority of works in ‘Vertigo of Color’ depict uneventful scenes. For instance, the piece that truly compelled me happened to convey nothing but a window.

Matisse’s ‘Open Window, Collioure,’ was painted from his studio overlooking Port d’Avall Cove, the iconic port that appears in many of Derain and Matisse’s most renowned works. The piece can be characterized by its bold and varied brush strokes, with paint taking the form of vibrant lines, dots, and streaks, to transform a simple view into an intricate collage. At the center lies the brightest point of the entire painting, consisting of different-shaped lines of pastel pink, blue, and purple that create the illusion of a vast, open sky. Boats are symbolized by overlapping yet distinct marks of orange, blue, and purple, angled to look as though they are prepared to propel into the sea at any moment. Surrounding the harbor is a plethora of greenery, drawn in darker shades to contrast the lighter media. The darkest portions of the painting are concentrated on the outer edges, furthering the appearance that there is a single beam of light illuminating the painting. These seemingly small artistic decisions work harmoniously together to create a piece rich with depth and eccentricity.

Fauvism is fundamentally about minor details. A strategy often utilized by Derain and Matisse to embellish their paintings was to simply leave certain portions of the canvas bare. In ‘The Port of Collioure’ composed by Derain, you can see small chinks of white canvas scattered throughout the middle ground and background of the piece, giving the illusion of a less congested scene.

Fauvism, regardless of its controversial and tumultuous upbringing, is objectively one of the greatest artistic movements of all time, having paved the way for an entirely new sphere of art and creativity. With that, it is critical to note that Fauvism would not be as compelling as it is if it could be captured within a singular article. Thus, I encourage anyone intrigued by the matter to explore further and read the MET’s full description of Vertigo of Color and to go to view the exhibition in person. ‘Vertigo of Color’ stands as a testament to the audacity and brilliance of Fauvism and is undoubtedly worth a visit to MET. Hop on the 4 train or the M86 and observe the revolution of those who dared to paint with the untamed hues of the artistic mind.

In a dim reality, Fauvists achieved the seemingly impossible feat of finding brightness simply by appreciating the monotonous acts of life.