Upon entering the Emilio Ambasz Institute at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), I could sense the historical tension of environmentalism merging with architecture. Looking past the blaring yellow sign, almost a warning, ‘Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmental Architecture,’ currently on view through January 21st, 2024, I saw minuscule models all concerned with combining the built and natural world, each claiming to have the perfect solution.

For humanity, shelter ensures survival. However, buildings account for almost 40% of the world’s yearly carbon emissions. Understanding that humanity’s existence means the destruction of the environment, architects have been designing with conservation in mind since as early as the 1930s.

Both realized and disregarded projects have reflected these ideals and are compiled into the first exhibit at the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Study of the Built and Natural Environment.

The Institute opened in 2020 and has now presented its first examination into the relationship between the world humans evolved into and the world we have made for ourselves. In a collection of projects spanning the 1930s to 1990s, the exhibit is a cohesive look at the historical nature of green architecture and aims to foster conversation between the past and present.

The mid-20th century saw the first major rise in concern for the environment. Through excerpts from her 1962 book, Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, the curators show visitors her perspective on climate change, specifically the impact of pesticides. This wasn’t the first time environmentalism was explored; however, the book was a catalyst for widespread discussion of how humans impact the environment around them.

In 1963, pieces of legislation such as the Clean Air Act, the Wilderness Act and the National Environmental Impact Act, among others, began to receive recognition by Congress in the United States government.

The first Earth Day was celebrated on April 22nd, 1970 and with over 22 million people nationwide protesting for increased environmental protection. Responding to the demands of the public, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established by President Nixon that same year to organize efforts for research and assembly of environmental regulations.

‘Emerging Ecologies’ aims to address the role architecture plays in conservation. The exhibit is a composite of several core ideas in environmental architecture: environmental enclosures, countercultural movements, environment as information, multispecies design, and green poetics. These concepts are vaguely outlined in the organization of the exhibit, easily flowing from one to the next.

The first component of the exhibit that draws the eye – other than the evocative sign indicating the exhibit – is the maps and models that scatter the room, each indicating a different way the environment influences how architects build. Differences in altitude, water level, and other factors, make it so that each ecosystem is unique and requires special planning to avoid problems down the line.

The Orme Dam is an example of how ignoring vital information impacts communities. In 1968, Congress approved a plan to build a dam along the Verde river that flowed through the Yavapai reservation in Arizona. However, the creation of the dam would have flooded over half of the reservation’s land. In response, protestors marched from the reservation to the state’s capital, Phoenix, in order to stop the dam’s construction. Following years of legal battles, the plans for the dam were canceled in 1981.

This map-filled area of the exhibit documents many ways to evaluate environments, taking into consideration practicalities such as altitude and temperature variations; it lacks the development of other aspects of environmental architecture of later areas. Rather the exhibition presents this information as building blocks for later experiments and explains the processes each researcher took to create these maps.

Following the natural arrangement of the exhibit, the next portion’s viewers amble through involves multispecies coalitions. As incredulous as it sounds, throughout the 1960s and 70s, there were entire collectives dedicated to exploring relations and possible cohabitation between humanity and other species.

One notorious example of this is the Ant Farm Collective’s ‘Dolphin Embassy.’ Noticing that dolphin brains were larger than humans, Ant Farm hypothesized that humans could communicate and live with dolphins. This sparked plans for immense ships that would sail across the globe with the ability for both dolphins and humans to control the steering wheel.

The layouts of these cohabitats are colorful and extravagant, consisting of multi-story vessels with pools circulating through each for the dolphins and slides connecting them. Of course, this scientific cruise drifted away from completion upon investigation into humanity’s actual ability to communicate and understand dolphins.

The exhibit presents the plans and information of the Dolphin Embassy in an unbiased fashion, leaving viewers to decide their opinions. Looking around, those examining the blueprints shared a collective bewildered expression.

Just as extraordinary as communicating with dolphins was the rise of enclosed ecosystems. This medium of green architecture rose as architects aimed to use fewer natural resources by creating self-sustaining areas. These ideas expanded into larger objectives until some scientists theorized that humanity could inhabit space full time by the year 2000.

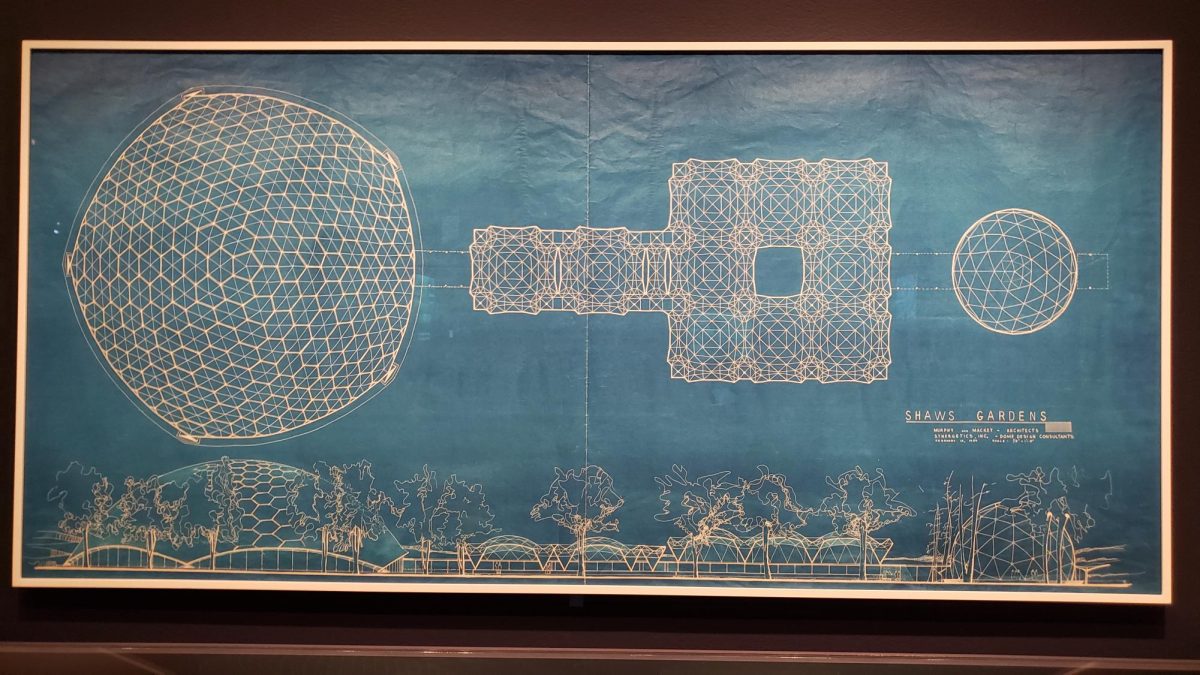

In these ecosystems, an enclosed dome typically surrounds an environment and pulls resources only from that area. A successful example of this is the Climatron enclosing the Missouri Botanical Gardens. Opening in 1960 and inspired by Buckminster Fuller — a prominent architect who invented the geodesic dome — the closed off ecosystem supports a variety of flora, with one computer that controls all temperature, irrigation, maintaining order in the dome.

Indulging in the potential of enclosed environments, society in the mid-20th century was preparing for their next frontier, space. The idea that humans could live full time outside of Earth was anticipated, and designs such as the Stanford Torus and Bernal Sphere were emerging from the many institutions. Ecosystems that could sustain themselves would be useful in the barren void of the universe.

Geodesic domes were also seen in the countercultural movement of the time, circulating through the “hippy” groups of America. This movement aimed to defy normal standards of American living at the time, living off grid or in collectives in order to use less resources across communities. Specifically, the New Alchemy Institute (NAI) in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, provided a research center for investigation into organic agriculture, aquaculture, and bioshelter design. They utilized the ideas of Buckminster Fuller in the design of their center, which provided more sunlight without compromising on insulation.

Another successful project to come out of the countercultural movement was Drop City, an artist’s community of geodesic domes in Southern Colorado. First formed in 1960, the area utilized the domes to combat fierce weather typical of the area.

On the other hand, some architects chose to keep their standard building facades, adding ecocentric meaning to their work. These structures incorporated flora into their presentation or blended in with their surrounding areas, urging passer-by to look for deeper interpretation than their brick and mortar.

Through green poetics, Emilio Ambasz’s Prefectural International Hall in Fukuoka, Japan defines the trend. The institute at the MoMA being the namesake of Ambasz, it seems rational that the architect would have some prominent work in environmental architecture. This building in particular represents a step stool, and each roof is lined with public parks and an abundance of plant life.

Being that the building replaced a park, the Prefectural Hall is a gleaming example of how care for the environment and meeting the needs of the public can be balanced.

The exhibit at the Emilio Ambasz Institute is labeled as “emerging,” yet it doesn’t place center focus on the modern-day inquiries into environmental architecture. Simply put, the exhibit aims to provide historical examples of what is possible within the realm of architecture. Understanding the warnings of the past can pave the way for future progress.

If one wishes to seek out a modern opinion, pulling back a curtain reveals the exhibit’s contemporary opinions. The exhibition showcases present-day architects – Mae-ling Lokko, Jeanne Gang, Meredith Gaglio, Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, Amy Chester, Carolyn Dry, and Emilio Ambasz – and their thoughts on what needs to be done moving forward. The exhibit utilizes headphones as a useful resource to eavesdrop on the recorded conversations of these contemporaries.

The sum of these parts of the exhibit aim to propel future preservation movements. As climate change continues to influence all around the world, there is renewed pressure to regulate energy consumption and efficiency when building. The exhibit provides a lens through which architects could look back on and learn from.

In times where architecture is increasingly focused on conservation and ecological logistics, ‘Emerging Ecologies’ looks back on all that humanity has accomplished or experimented within environmental architecture.

Understanding that humanity’s existence means the destruction of the environment, architects have been designing with conservation in mind since as early as the 1930s.