Tracing Terruño, Muriel Hasbun’s exhibit of her photography, located on the second floor of the International Center of Photography, is lacking in color. Throughout the three-room showing, a first for Hasbun, there are few bursts of light or pigment. One of the few comes right at the entrance in a mixed-media projection of Hasbun’s videography from her most recent trip to El Salvador, her birthplace. The video follows her and her ailing grandmother as she narrates the history of the country. A particular vignette focuses on her grandmother’s breathing tube as it fogs up from her warm breath. It’s a little strange and quite beautiful.

In the show’s selections, there is a rejection of the traditional conventions of photography — or at least a rejection of the ones that I know. As you make your way through the open space rooms, you are confronted with bizarre and intimately crafted work. In the limited space given to her, Hasbun creates an intensely personal and often disarming story.

Born in El Salvador to a Salvadoran-Palestinian father and a French-Jewish mother, Hasbun has made a name for herself by sharing her uniquely eclectic background with the art world. Within her career, there is a breadth dedicated to her mother, Janine Janowski, a young woman forced out of Nazi-occupied France into Poland as a child. She moved back to a liberated France quickly after the Germans’ defeat but eventually moved to El Salvador to explore her own artistic inclination.

While in El Salvador, Janowski set up a massively successful underground gallery, “El Laberinto,” as the nation fell to civil conflict and eventually war. While there, she also met Hasbun’s father and had Hasbun herself. It’s here where a large collection of Hasbun’s work emerges and springs from. Hasbun summed up the relation between her photography and her native land well in Instruments Of Memory magazine: “One of the ways that I began to know and understand my history was to ask family members to share their family photos with me. The process was a non threatening way of starting a conversation which could at the very least give me factual, straightforward, biographical information about the family members pictured (such as birth and death dates, places of residence, names of spouses and children, etc.), to then be able to discuss more difficult events in their lives (such as migrations, separations, losses, etc.), or the nature and quality of their relationships.”

In Tracing Terruño, Hasbun makes good on that thesis, positioning herself at the precipice of personal photographic storytelling. The collection has amassed an impressive collection of work from Hasbun’s projects, including Santos y Sombras (Saints and Shadows), X post facto, and Pulso: Nuevos registros culturales (Pulse: New Cultural Registers). Ranging from 1988 to ideas just being revealed to the public now, the IFC has lived up to the pressure of opening Hasbun’s first real exhibition in the New York area.

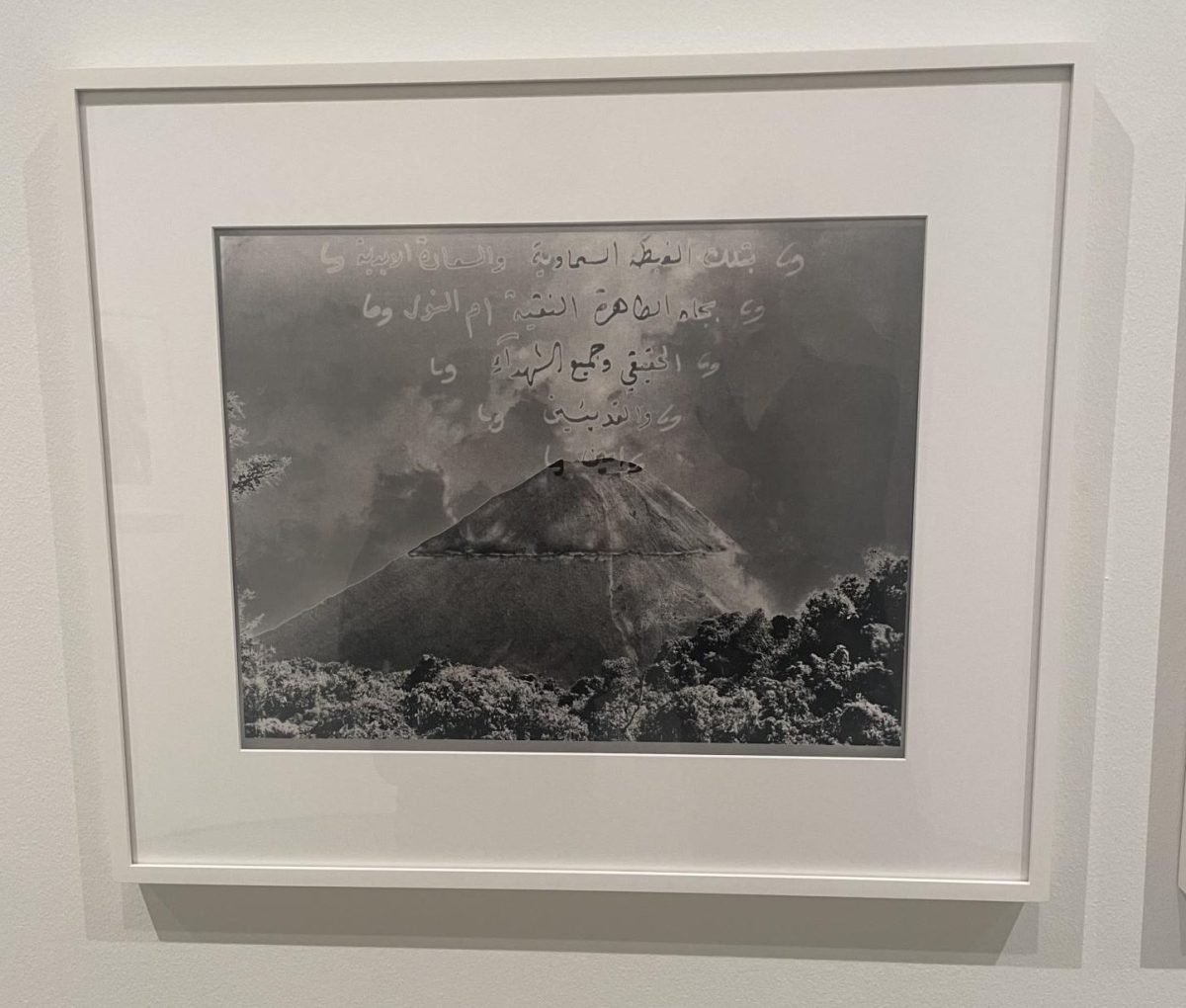

Immediately opening the exhibition are some of Hasbun’s newest pieces from Pulso: Nuevos registros culturales. The collection, featuring works from 2019 to 2021, focuses largely on depicting El Salvador in flux through the 80’s and 90’s. Pieces are often imprinted with two images: a seismograph printing of the land’s movement and development through time and rescued prints from her mother’s photography gallery: El Laberinto.

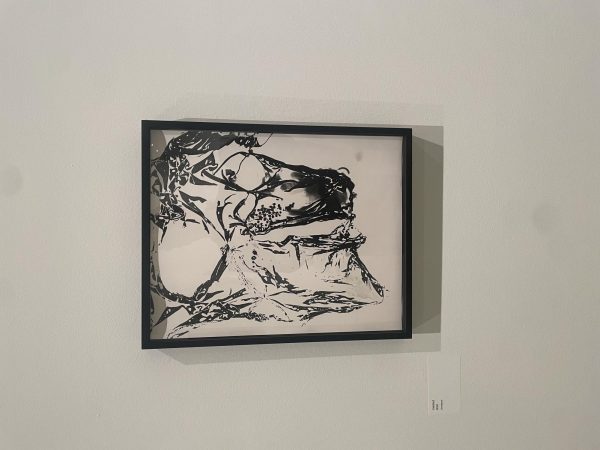

The decision creates a ghostly effect; the art is raw and often unpolished. Images are dark and washed with intensely jagged lines showing off the grand movement of the dirt. White scratches from the seismogram give shape to an undefined and unending human figure in Pulse: Seismic Register 2020.02.28. Hasbun masterfully creates ghosts out of images, physically showcasing movement through her mother’s colossal collection of work.

Over ten years earlier, Hasbun showcased the same willingness to explore the paranormal in her art in X Post Facto, an intimate examination of her father’s dental practice, with real images of the teeth he operated on. The idea on its face is “in-your–face” craftsmanship, almost a statement of creativity more than anything else. But in application, the photos are powerful statements of existence and visibility for a group too often ignored.

Hasbun meticulously reprinted original x-rays of patients’ teeth on their original negatives from her father’s original practice. The system was long and tedious but when put all together in the high-ceiling white room to the left of the IFC staircase, the teeth grab you. Images of roots, nails in teeth, and cavities all lend themselves to the Salvadorians that Hasbun is attempting to dig out of a forced collective un-memory.

In an interview with The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Hasbun said “…I asked members of the public to write or draw their own stories of trauma occasioned by war onto one of my photos of X Post Facto. Through these different strategies of engagement, I’m assembling a collective archive that sheds light on the interconnections and shared experiences that exist between us, regardless of which nation’s passport we might happen to carry.”

The collection consists only of what Hasbun calls “documents signed with an X” but goes far beyond a simple X-ray. In gathering her father’s dental records from his time as a practitioner, Hasbun gathers people. The intimate photo record of their presence is displayed not independently, but rather in a grouping; Hasbun has collectivized teeth. One particular image stands out among the crowd; a nailed-in scaffold not immediately recognizable within the milky white tooth. Centered by a ghostly gray, the contrasting negative of the nail seems extra-violent. This is a very real invasion taking place right before us. Hasbun is simply reminding us of the situation at hand with her deeply unique gift.

Finally, as you step around the final corner of the exhibit, a final series greets you: Saints and Shadows, or Santos y Sombras. According to Hasbun, it’s a reckoning for the artist. She wrote in Revista Magazine in 2016 that, “Since 1990, I have committed my creative energy to developing a body of work that explores my family history and sense of identity. Santos y sombras is a refuge against silence and forgetting.”

The series of black and white reprints is made up of double prints; portraits of family members, friends, and strangers are superimposed over land-scapes of towering mountains, wide fields, and intimate living spaces. The photographs sum up Hasbun’s thesis well, the idea that land is people and people are land. El Salvador is a living and breathing entity made up of shadows who, thanks to Hasbun, have been able to leave their own unique mark on the expanse they inhabit. The work rounds out the exhibit for a reason, it’s beautiful and concisely Hasbun.

Hasbun has made the emphatically generous gift of sharing her connections few and far between with long-gone generations of family at the ICP. If this is all she has left to give, we should still consider ourselves very lucky.

The exhibit closes on Monday, January 8th, 2024, so see it over the next few weeks before it is gone.

Hasbun has made the emphatically generous gift of sharing her connections few and far between with long-gone generations of family at the ICP. If this is all she has left to give, we should still consider ourselves very lucky.