New York’s New Gilder Center: A Transcendent Fusion of the Arts and Sciences

The American Museum of Natural History’s new building opened on May 4th, 2023, welcoming visitors from across New York City and the world.

New York City’s blocks of buildings are admired by any who consider themselves to be architectural connoisseurs. The centuries of populations that have resided in the ‘City that Never Sleeps’ have left a lasting mark, seen through the city’s buildings. One block may present to a passerby a Gothic style church, with its pointed arches and stained glass windows, but as you continue the walk, a skyscraper of the International style may catch your eye. The use of steel and reinforced concrete, enveloped by long strips of glass windows, cause an onlooker to wonder in awe about the edifice.

Throughout the city, different architectural eras seem, to a certain extent, to be geographically spread out – sleek modern buildings soar into the skies of midtown echoing the hectic nature of the neighborhood, and the Beaux-Arts buildings of Greenwich Village reflect the neighborhood’s tranquil atmosphere. Either way, this rule does not seem to apply to the four square blocks of the Upper West Side that make up the American Museum of Natural History.

Walking the park perimeter of New York’s natural history museum gives one the sense that it is not just a building, but an assemblage of architectural extensions added throughout the years. The east entrance to the museum holds a collection of Corinthian columns, adorned with a triumphal arch, creating a monumental entrance that embodies the intellectual and political power of the natural sciences. To the south, a Romanesque revivalist facade protects a secondary entrance of treasures within, while the northern glass cubed planetarium encases the otherworldly sciences, commonly associated with themes of futurism and modernism, particularly prevalent at the year of the building’s construction in 2000 at the beginning of a new digital age.

Over the years, the building’s original 1877 structure has evolved in part to allow space to hold the growing numbers of museum collections that AMNH scientists have collected over the years. Along with this, it has also transformed to project continued messages that the museum hopes to represent as a scientific institution. Science explores the unknown, experiments with the uncertain, and offers hope and answers to the endless mysteries of the world.

With the opening of the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation on May 4, 2023, the museum has exhibited a new message regarding the intertwined, yet seemingly contradictory nature of both the arts and sciences.

The new building’s architectural structure represents this idea most directly. The complex is designed by the Chicago-based Studio Gang, an acclaimed architectural and urban design firm led by architect Jeanne Gang. Through her past projects, Gang has created a clear style — a seamless integration of the natural arts. The architectural interventions often emphasize the use of natural materials, light, and space in order to evoke a sense of harmony and tranquility, which is an approach rooted in the belief that incorporating allegedly contradictory elements can enhance human experience, as well as promote a sustainable future in the world of architecture.

This natural, yet modern theme in Gang’s work is clear in the new Gilder Center’s structure. The $465 million building had an operative idea, stated by Jeanne Gang herself: “How can space contribute to human’s natural desire to know more and learn more?” The building is inspired most directly by a canyon — at first glance, a carving through stone by wind and water. Yet the more one looks at it, the shapes transform as they do over millennia, forming a curvaceous and complex final product. With a primary building material of shotcrete, Gang was able to “carve” curves in the structure without any unattractive sharp edges or cladding joints.

The material makes up both the exterior and the interior of the Gilder Center, making the building look much more appealing and uniform. Yet while it may be pretty to the eye, the bumps are certainly uncomfortable for any viewers leaning over the edge of one of the many balconies in the building. In this sense, instead of smoothing out the material to make a more comfortable and naturally accurate space — as the slot canyons the building is inspired by are actually quite smooth in reality — the building is a bit of a white elephant.

Yet it is clear why the museum administrators wanted a building with a different look. As a visitor, it does not take long to get the sense that the complex, at least in regard to its appearance, is a tad dated. While the pink granite exterior of the Gilder Center is the same stone used for the Museum’s entrance on Central Park West, this seems to be the extent of the similarities between the new and the old. The darkened exhibition halls of the museum’s older buildings are mostly made up of vast displays, from life-size dioramas narrating a story of the natural world to glass cases, to others that show the most minute details of microscopic beings, yet they all share one similar aspect. They are, at most, displays. This idea, which is present in some of the other buildings in the complex that makes up the American Museum of Natural History, the ones devoted to exhibitions, is far from present in the new Gilder Center. Here, dynamic themes of immersion are what make up the building. The light-filled space gives the Gilder Center a less stuffy feel compared to the rest of the museum. The sleek, lines made from shotcrete give one a sense of satisfaction immediately upon walking into the building.

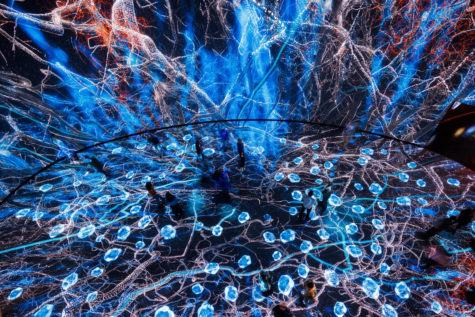

Themes of interactivity and immersion are extremely important in the makeup of the Gilder Center. The building’s Davis Family Butterfly Vivarium allows visitors to be face-to-face with the beautiful insects. An exhibit one floor below, in the Solomon Family Insectarium, hosts one of the world’s largest displays of live Leafcutter ants; they are shown inches away from viewers through clear cases. Along with this, Gilder’s 360-degree Invisible Worlds experience gives the feel of the other immersive experiences arising in the art world, such as the Van Gogh Experience, yet with more of a scientific twist.

Nonetheless, it does seem fitting that American Museum of Natural History has decided to shift their take on exhibitions as time proceeds. 21st-century museum-going is constantly battling attention spans that are much more intrigued by headphones and screens. Rather than simply showcasing ancient artifacts in a mausoleum, the Gilder Center suggests that we, too, are part of a living, breathing zoo that is certainly not unwelcome.

With its undoubtedly reverential appearance, many cannot help but wonder if some of the reason for the construction of the new building was to create a new event space, adding an alternative to the beautiful, yet slightly tired, Milstein Hall of Ocean Life. While it is probable that Gilder’s main atrium will be used for galas and other events, the Center does something much more than that for the rest of the museum complex: it links to parts of the museum that were once dead ends.

If you have ever visited the American Museum of Natural History, you know that at moments, it can be difficult to navigate. As the museum continued to construct new buildings to hold its growing collection of artifacts, the original courtyard in the center of the complex also filled with buildings, creating a somewhat frantic and crowded space.

While the museum team may never be able to completely squeeze new buildings into a complex that simply does not quite fit into its original form, the Gilder Center does help. Its addition connects to several surrounding halls of the museum that were originally cut off, replacing them as ongoing loops.

When it comes to the building itself, the myriad of exhibitions, while possibly less in-depth than the exhibitions established in the other buildings of the museum, the Gilder Center’s attractions are undoubtedly intriguing, engaging, and altogether inspiring.

Upon entering the building, instead of being surrounded by cases of artifacts, one looks to their right to see an entire wall of the main hall made up of glass, with the other side showing a typical collection’s storage room. Here, drawer after drawer line the room, filled with ancient fossils. From this first “behind the scenes” look, it is clear to any visitor that the Gilder Center is taking a unique position on how a typical “museum visit” should go.

Up the rounded, canyon-inspired stairs, the visitor is taken from the main hall to the second level, where more exhibitions are found. Aside from the gaping holes in the wall, most likely meant to symbolize looking to natural inspiration for the structure, the Davis Family Butterfly Vivarium, originally a seasonal experience for visitors in one of the museum’s older buildings, is found here, now open year round, along with the Solomon Family Insectarium found near the entrance of the building, both designed by Ralph Appelbaum Associates.

While both of these attractions will be sure to entice visitors, for me, the most revolutionary exhibit is the Invisible Worlds experience. Upon initially hearing of it, for me, the attraction sounded like it might be redundant and uninspired. In 2023, the idea of a new immersive experience is close to being tired out – we have all seen 360-degree video experiences, and while the first one may have seemed cool, at this point they have become repetitive. However, the Invisible World exhibit, designed by German group Tamschick Media+Space, takes a new twist on the idea of an immersive, visual experience, incorporating scientific thought into a field that is typically art-dominated.

Marc Tamschick, the company’s CEO and creative lead, began working with audio/visual immersive art in 1994, when the art technique was actually referred to as “inverted mapping,” since the artist is projecting something into a room in an inverted sense. From here, Tamschick established the Media+Space team, exploring many projects on both human and natural behavior, as well as how the two interact with each other.

The group typically works with science museums, and they have a main goal of assimilating the divergent fields of the arts and sciences, both of which seemingly oppose one another. However, according to Tamschick, the Invisible Worlds exhibit took over ten years, making it the biggest project that the team has taken on so far. Tamschick said, “Doing something of this size and dimension, it is our first time, but we have done many projects that show different aspects of both art and science, all that culminate into this one.”

While the theme of the exhibition was always meant to reflect the idea of “invisibility,” the story it was meant to tell has developed quite a bit over the years of its creation. The initial plan was to create a show that told a story through the perspective of a microscope, giving the audience the point of view of a museum scientist (a continuation of the see-through walls of the main hall, giving insight into the work and storage rooms of the curators at the American Museum of Natural History).

However, this idea eventually became incorporated into another, meant to integrate viewers into the dioramas held in the museum’s older buildings, creating the experience of simply observing a diorama or exhibition into something much more interactive. Working with many of AMNH’s own scientists, Tamschick was able to construct a scientific narrative through his art form, stating, “The space eventually became a piece about everything; about how really everything is connected, because that is the one thing that any scientist will tell you.”

The final product of the Invisible Worlds exhibition explores various networks of life at all scales, including those that are too fast, too small, or even too slow for the human eye to observe. In the Tamschick group’s eyes, the beauty of audio-visual art forms, like those they focus on, is that they can appeal to all ages and all intellects. Particularly for a museum that has viewers from all over the world, it is crucial that the American Museum of Natural History has a more immersive strategy, in at least some of their exhibitions, ones that appeal to everyone. Tamschick described this idea as he said, “My goal is to create work that is a heart-opener. For younger kids, the hope is that it will help them understand that all of these galleries are something that they could be interested in. For the older audience, maybe they will learn something new to help them gain a better understanding of the world later in life.”

Regardless of whether the experimental nature of the Gilder Center should be viewed with celebration or skepticism, it is clear that a new era of science’s presentation is emerging. There is no doubt that the American Museum of Natural History’s most recognizable attractions – the iconic Irma and Paul Millstein Family Hall of Ocean Life (more commonly known by its famous Blue Whale model), the Hayden Planetarium, and even Lucy, one of the world’s oldest human fossils – will remain iconic. Yet the Gilder Center adds a new chapter to how the stories of science can be told. It fits into contemporary time much more than the museum’s current buildings, and it undoubtedly ushers in a new creative perspective on the narratives of the sciences.

For those who grew up visiting the American Museum of Natural History, seeing a clear break away from the dioramic nature of museum exhibitions present in the rest of the museum complex might have created a nostalgic sense of uncertainty as the Gilder Center first opened. However, the Gilder Center’s opening has also created a sense of hope that the museum will be able to thrive, regardless of the technological and artistic advancements that are happening in the world around it. In fact, modern growth can even help the museum to thrive.

“The space eventually became a piece about everything; about how really everything is connected, because that is the one thing that any scientist will tell you,” said Marc Tamschick, the CEO and creative lead of Tamschick Media+Space.

Claire Elkin serves as an Editor-in-Chief of The Science Survey, where she not only oversees the editing and writing of articles but also brings her passion...