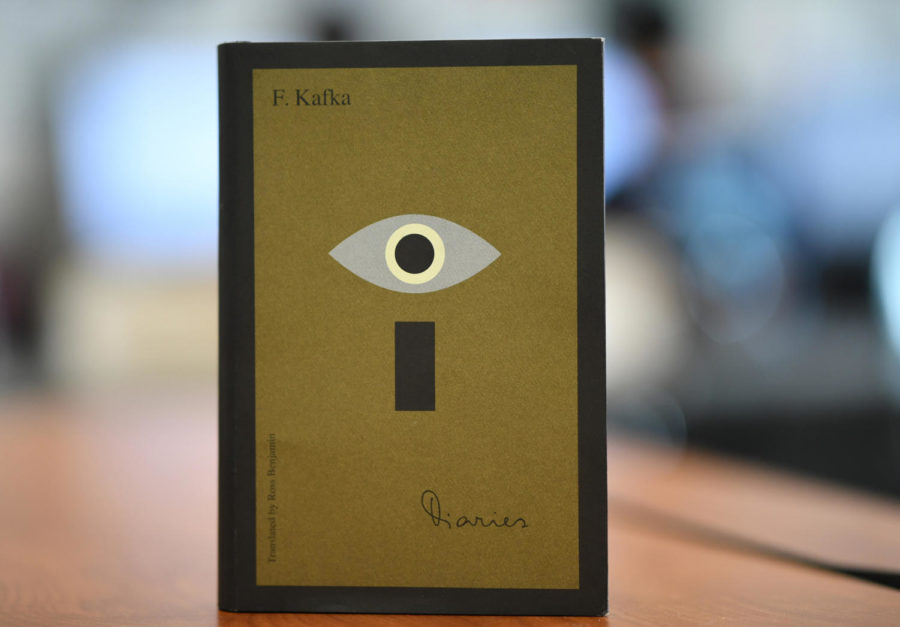

A Review of the New Translation of ‘The Diaries of Franz Kafka’ by Ross Benjamin

Ross Benjamin adds an essential new chapter to the story of a writer whose legacy is largely defined by acts of translation.

It took Ross Benjamin over a decade to complete his new translation of Franz’s Kafka’s complete, unabridged diaries, which was published by Schocken Books earlier this year.

“Traduttori, traditori” goes the old Italian proverb. Ironically meaning “Translator, traitor,” it’s a bold claim with some obvious truth to it. Anyone who’s taken a foreign language class or seen a disappointing movie adaptation of their favorite book knows that there are pitfalls to translating words and ideas across languages and artistic mediums. Nuances are lost, and we end up with Baz Luhrmann Great Gatsby or a heavily Google translated song from Frozen where Elsa sings about discrimination law and tells the listener to “Give up” instead of “Let it Go.” Failed translations like these are sometimes frustrating and dejecting, sometimes funny, and never as potent an artistic statement as the source material.

Not so of Ross Benjamin’s new translation of The Diaries of Franz Kafka, which is very good. It is so very good as to be an essential companion to Franz Kafka’s (1883-1924) fiction for anyone who wants to understand Kafka as a writer or as a person.

Kafka, the German-speaking, Jewish Pražan who wrote “Die Verwandlung” (“The Metamorphosis”), and “Der Process” (“The Trial”) is one of the central figures of modern world literature. His peculiar fiction juxtaposes the blasé with the bizarre, blends familiarity with estrangement, and uniquely illuminates the absurdity of a society obsessed with imposing order upon a disorderly world. His work has crept into the literary canon as the many-legged tour-guide of the industrial age, guiding readers through a world that suddenly seems far away from itself. Kafka is staggeringly complex, and his journals are an especially tricky part of his literary oeuvre.

Luckily, (or perhaps necessarily) Ross Benjamin’s qualifications for translating them extend beyond simply knowing German or being a distinguished academic. He’s also a lifelong Kafka fan.

In a guest essay for The New York Times, Benjamin tells the story of reading Kafka aloud with his friends as a teenager and “laughing out loud” at what he heard. Reading that reminded me of my own Kafka origin story, which is different from Benjamin’s in a few key ways.

I first read Kafka in my sophomore year of high school, when I heard that during his time at Bronx Science, novelist E.L. Doctorow ’48 published a short story called ‘The Beetle in the school’s literary magazine Dynamo, because Doctorow was in a self-described “Kafka phase.” I wanted to be Doctorow, so I set about entering a Kafka phase of my own, with vague intentions of eventually publishing a story in Dynamo called ‘The Insect’ or something similarly original. That story never materialized, but I did write an article for this publication about Kafka wherein I argued that his work will reach its peak social relevance sometime in future, after the ongoing digital revolution has run its course.

My Kafka phase lingered, and he soon became the patron saint of the adolescent isolation I felt (and still sometimes feel) as an aspiring writer attending one of the most competitive STEM high schools in the country. Doctorow was closer to my time and place, but the things I learned about Kafka — his crippling self-doubt, his years of unfulfilling work as an insurance clerk, and the fact that he was virtually unknown as a writer until after his death — bridged the almost-century-wide gulf between us. He was my literary idol, and the person I saw staring back at me from his stories was my close friend. Unlike Benjamin, my Kafka was not laugh-out-loud funny, nor was he the kind of social creature I could bring around my family or real-life friends. My Kafka was bleak, somber, and fiercely alone. Two years later, I am closer to Kafka’s fiction than I ever was, but Benjamin’s translation of Kafka’s Diaries raises doubts about how well I (or anyone) really knew him.

Benjamin’s version of The Diaries succeeds on several fronts. Benjamin makes the first two achievements explicitly stated goals in his thoughtful translator’s preface, but there are also implicit features that are just as (if not more) notable. These successes overlap a lot, but for the sake of organization I’ll handle them one at a time.

First, and most often reported, is the fact that this translation is a major correction of the record on The Diaries of Franz Kafka. Kafka died young of tuberculosis, and in his will, he ordered his friend and fellow writer Max Brod to burn all his unfinished work, including his choppy, in-progress diaries and several manuscripts for novels that have since become classics. Spoiler alert, Brod did not do as Kafka requested, and by the 1960s Kafka was regarded worldwide as one of the greatest writers of all time. However, Brod did not just send the unaltered manuscripts to publishers with a sterling letter of recommendation; he gave them an edit that Benjamin claims censored the spirit of the original text.

“The Brod edition … shied away from … linguistic fidelity for the sake of a more polished impression that might seem less unfamiliar or even jarring in places,” writes Benjamin in his translator’s preface. “Brod’s editorial interventions reflect his commitment to minimizing the fragmentary nature of the diaries and effacing the peculiarity of Kafka’s language in favor of a more formal, perfected, and supposedly pure High German.”

By changing Kafka’s language, Brod effectively censored his dead friend even as he gave his writing to the world. Brod also did even less savory things, like removing entries that hinted at Kafka’s sexual life or painted Brod in a bad light.

So instead of translating from Brod’s edited version of the Diaries, Benjamin used an unabridged German critical edition of the manuscript published in 1990. Benjamin argues that this makes all the difference, and I’m inclined to agree.

Brod’s polishing of Kafka’s work didn’t just sand down some of the edgier entries, it surgically removed the improvised, fragmentary quality that is now the essence of Benjamin’s version. The preface compares them to studio outtakes, but I think the brisk, often unfinished, sometimes outright nonsensical diary entries are more like newspaper clippings or shreds of torn up plane tickets. Out of the context of Kafka’s mind, they take on a life of their own, and the reader can easily imagine how each one could have blossomed into something greater.

Take for example the following entry:

“What do you want then? Come — We don’t want to. Let us be! –”

Is this a quote from someone in Kafka’s life? A piece of a story? An errant thought? A prisoner talking to a warden on behalf of his fellows? A mouse protecting her family from a predator? Throughout the book Benjamin’s subtle but deft hand preserves all those possibilities and more, lending the book a Rorschach test-like quality that forces interpretation out of the reader. It’s very engaging.

Benjamin’s second major success is his humanizing of Kafka as a man. This translation shatters the illusion that Kafka was — as I myself, Brod, and many others believed — a “saintly martyr to literature,” full of nothing but gloomy loneliness in the face of the absurd. The diaries present a complex person who felt joy and pain in equal measure, and often at the same time. Kafka has moments of strength (“For a moment I felt encased in armor”) and moments where he laments his apparent separation from the world (“Who will confirm for me the truth or probability of the notion that it is only due to my literary calling that I am otherwise uninterested and hence heartless.”)

Interestingly, The Diaries capture much more than Kafka’s perception of himself. Entries cover a wide range of activities Kafka participated in, from long reviews of plays he saw to accounts of interactions with his friends and family. Kafka comes across as far from a reclusive genius. At times, he seems almost like a man about town.

Benjamin insists that he doesn’t have the power to deliver a comprehensive picture of Kafka the man to his readers, but he fills in enough of the gaps in popular knowledge to take him down from the lonely pedestal that Brod and others placed him on.

Finally, Benjamin’s translation of the Diaries shares the quality of all great translations, namely, that it justifies itself by implicitly acknowledging that translation is ubiquitous and thus immeasurably valuable.

Throughout my reading of this book, it became clear to me that German to English is not the only, or even the most important type of translation that must occur for readers to read Kafka, or anything else for that matter.

I’ve already touched on Brod’s bad faith translation of Kafka, but there’s also the reader’s translation of the fragments Kafka leaves on the page. In choosing one of the possible interpretations of Kafka’s incomplete diary entries, readers are translating what they read even as they read it, filling in the blanks that Kafka left and Benjamin lovingly preserved.

Even Kafka himself, by putting pen to paper in (as Benjamin describes it in his guest essay) the “[loose], less formalized” style of his diaries, was performing an act of pure translation, taking his complex thoughts and feeling about the world around him and turning them into something that could make the fifteen year old Ross Benjamin laugh out loud over half a century later.

One cannot help but notice these ripples of translation when reading the Diaries, and they illuminate a universal truth, that every written word, in one way or another, is translated. So to once and for all put to bed the accusatory Italian proverb, while some translators can abuse and distort their source material, faithful translation across languages is as beautiful and creative as writing, or reading. And even more importantly, without these explicit acts of translation across language barriers, we wouldn’t be able to identify the subtler cases of translation that occur in our own minds.

Kafka has been betrayed, but without Brod’s initial choice to go against his friend’s wishes, the world would have been robbed of some of its greatest works of literature. Without the initial appeal of an angsty role model, I would never have been drawn to Kafka in the meaningful way that I was. Though Benjamin gives us a clearer picture of Kafka and his work, he is not just correcting the record. Benjamin gives readers the tools to interpret Kafka responsibly, to become translators ourselves. A different proverb proves true: the truth sets Kafka free.

This, of course, means that any attempt to impose objective truth onto Kafka’s work is ultimately futile, and fundamentally absurd. And even if we can’t know for sure if that notion would have made Kafka laugh, at least we now know that it was a possibility.

To purchase a copy of Ross Benjamin’s new translation of The Diaries of Franz Kafka , click HERE.

Ross Benjamin’s qualifications for translating them extend beyond simply knowing German or being a distinguished academic. He’s also a lifelong Kafka fan.

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...