The Painting of Humanity: The Ways in Which Art Defines Points in Time

Even before the documentation of written language, art was used as a method of storytelling. Today, we tell the stories of those artists.

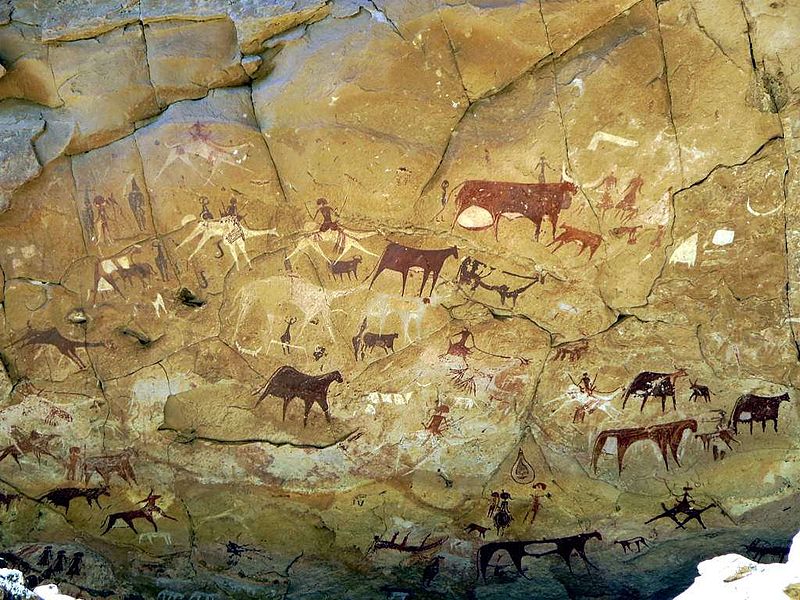

David Stanley from Nanaimo, Canada, CC BY 2.0

Early cave paintings focused on subjects such as humans and animals. Artists used their fingers as brushes or made tools from stone, animal bones, and blow pipes.

Art history is a term often associated with memories of museums filled with silence, broken only by the occasional cough or meandering footsteps of onlookers. But in reality, it is a complex field that allows historians to piece together the story of humanity. Art contains valuable clues to the past, all of which better inform the narrative of history and evolution.

Art is a creative field that continues to evolve and grow, while simultaneously reaching into the past. With technological advancements, our understanding of early art becomes more complete. Nevertheless, artists are constantly changing what defines art. The ‘starving artists’ who struggled to make a name for themselves now have the last laugh, as much of the modern art world revolves around their work.

EARLY CIVILIZATION

Roughly 45,000 years ago, the ancient art of cave painting was born. In 2018, archaeologists identifed a painting of three wild pigs, native to the Indonesian island Sulawesi, as the oldest known form of representative artwork. Representative and non-representative artwork are two categories of art classification. The former, as exemplified by the Sulawesi pigs, refers to art that portrays something realistically, whereas non-representative art is more abstract. Although two of the pigs have been damaged and faded by time, the third stands in remarkable condition. Upon further examination, archeologists found that its creator used ochre, a reddish-brown pigment. Ochre is one of the world’s first paints along with charcoal and calcite. Painter’s tools such as stone grinders and hollow-bone brushes date even further back than this painting.

The simplistic nature of early art often reveals the objects of societal value and core beliefs during its time. In early civilizations, tools and evolution of art style was limited. Nonetheless, artists used natural pigments to the best of their ability in order to cover their rock canvases with stories of hunters, often alongside animals. Even though the drawings are simple, historians found an important connection to humanity’s history in every stroke. Before the introduction of multicolor factory-produced paint, pulverized plants and even substances such as animal blood were used for their intense pigmentation. The concentrate would later be mixed with animal fat, which created a texture resembling paint.

Commonly used pigments included the clay-like substance ochre for red, calcite and kaolin for white, and blazed charcoal for black. These paints were used to record information through hieroglyphics, and even appeared in the first calendars. Although early painters were entirely unaware of the historical significance of their artistic expression, their paintings always had a purpose. Many historians cited possible reasons such as a positive influence on the hunt, or purely for the aesthetic appreciation of nature. The latter argument, which is often coined “art for art’s sake,” indicates the human desire to express creativity. While art has many purposes and benefits to society, it is still important to recognize the existence of work that exists to be art and art alone.

THE EUROPEAN RENAISSANCE

One of the most well-known periods in art history is the European Renaissance, a time of classical revitalization for literature, art, and music. It was lively, joyful, and came in the wake of the most devastating pandemic known to mankind: the Black Death, a 500-year plague that swept through Europe during the Middle Ages. Spread by infected rats exacerbated by an intense period of commerce and trade, the chaos left behind was unheard of. Society became grief-stricken and without order.

And yet, historians remain at a loss for how the plague itself subsided. What is known is that eventually, the gripping terror that had taken Europe by storm was replaced by a desire to make radical changes to society. Enter humanism, a philosophy that encouraged the exploration of the individual rather than the reliance upon a religious deity. Such ideals paved the road for the Renaissance, which led to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment.

At its core, European society experienced a great shift. First came the “rebirth” of art appreciation and education. The most important difference between Renaissance art and that of earlier time periods was the change in attitudes toward religion. Renaissance art strayed from traditional iconographic styles. Though religious stories were often featured, they were painted with less reverence. Earlier medieval art had incorporated architecture into mosaics and paintings, enhancing the worship of “larger-than-life” religious figures and symbols. Renaissance art chose to feature society’s interactions with such symbols, as seen in pieces such as The Wedding at Cana. Paolo Veronese captures a moment from the wedding where Jesus allegedly turned water into wine. What is unusual about Veronese’s work is the distribution of focus. Jesus sits in the middle of the frame, and yet is painted with the same proportions, color palette, and detail as the rest of the wedding attendees. The only indication of Jesus’ elevated status comes from an aureole around his head. Here we have a societal harmony without the ritualistic worship of religion, perfectly explained by a work of art.

The scientific equivalent would later appear with Galileo and his ongoing struggle to promote scientific thought without the banishment of religion. To many during his time, the idea of a true coexistence between religious belief and scientific knowledge was revolutionary. And yet, artists were able to convey the same message years before scholars and their word.

CONTEMPORARY STORIES

Contemporary art, which refers to a large majority of the art practiced today, is a perfect example of a societal snapshot. For example, digital art represents the desire to improve technology and expand its capabilities. Digital art addresses the issue of travel because it allows artists to use computers, phones, tablets and more, in order to experiment with different tools and mediums. In contrast to traditional art supplies such as canvases and expensive paints, many art applications are free or only require a one-time-purchase. Furthermore, the introduction of content creation and social media platforms allows artists to gain recognition and exposure around the world.

As humanity has evolved, a desire to use art as a form of self-expression has become more prevalent. Although there is no single reason that humans create art, its purpose varies with its time period. Ancient Greeks and Romans worshipped gods and believed they often assumed human forms. In order to display their loyalty, sculptors created statues in meticulous detail in order to fill temples. In a post World-War society, artists expressed chaos and the irrationality colored by that era. Surrealism, characterized by organic shapes that warped reality, rejected the norms of traditional art.

Recently, artists have taken it upon themselves to metaphorically rock the boat, often utilizing elements of comedy, satire, and shock to send a worldwide message.

Take the famed performance by Jens Haaning, a well-known Danish artist. Haaning was commissioned by Kunsten Museum director Laase Andersson to recreate two of his previous works. The works, titled An Average Austrian Year Income and An Average Danish Year Income, feature sums of money presented on a canvas. Andersson asked Haaning to recreate the two works as parts of a larger exhibit, Work It Out, which was intended to showcase pieces with a focus on the workforce.

Provided with two blank canvases and partial funding for both recreations, Haaning was struck by a new idea. When museum staff opened the packages sent by Haaning, they discovered two blank canvases. Frustrated and amused, Andersson placed Haaning’s empty canvases on display, under Haaning’s revised name: Take the Money and Run. Jens Haaning, who made it out with the equivalent of $84,000, has no qualms about his decision. “The work is that I have taken their money,” Haaning said to the Danish radio station P1 Morgen. Haaning went on to explain that even with the funding provided, he would have been forced to cover the remaining cost with his own money, nullifying any profit he would have received from his contribution.

Another such example comes from the famed street artist Banksy. In 2018, his piece Girl With Balloon had just sold for a bid of $1.4 million, when suddenly the unexpected struck. Auctioneers whispered in shock as the frame whirred to life and began to shred the painting. Banksy, as it was later revealed, had placed the painting inside a special frame. The event caused quite a stir, and the price leaped to a staggering $25.3 million. Unfortunately, the incident was unable to get the artist’s intended message across. Banksy, an English artist who has managed to maintain anonymity for nearly 30 years, enjoys making street art available to the public. In fact, the mere act of auctioning one of his paintings can be considered a betrayal of his ideals.

Art can tell brilliant stories about society or the artist themself. Time and time again, artists strive to break the mold and create a place within the tapestry of humankind. With the right materials, dedication, and time, artists will undoubtedly continue to tell their stories and use their passion to speak for many. Banksy’s Girl With Balloon may go down in history as a failure, as the artwork sold for a higher price due to its unique half-shredded quality, but the original intent is undisguisable. Literature can be censored, and photographs can be edited or captioned to tell a different story. Art dances on the line in between, presenting narratives that permits a sense of interpretative mystery. It is no wonder that art can be preserved and studied from nearly 50,000 years ago.

Jens Haaning, who made it out with the equivalent of $84,000, has no qualms about his decision. “The work is that I have taken their money,” Haaning said to the Danish radio station P1 Morgen.

Sam Chin is an Editor-in-Chief and Chief Graphic Designer for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. In...