A Journey of Great Ups-and-Downs: Carl Jung’s Visionary Insight From ‘The Red Book’

In a time where modernity stifles passionate minds, Carl Jung reminds us of the human soul in his leather-bound manuscript, ‘The Red Book.’

The original uploader was Ekabhishek at English Wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

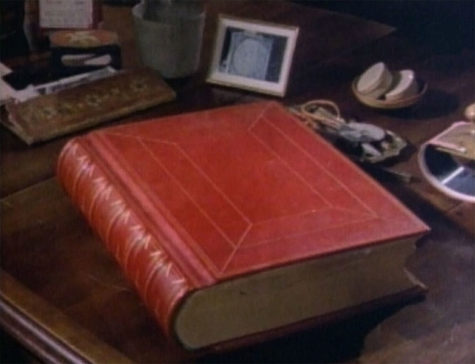

Bounded by an elegant leather frame, the words ‘Liber Novus,’ Latin for ‘New Book,’ stand out on the front cover of Carl Jung’s ‘The Red Book.’

“My soul, where are you? Do you hear me? I speak, I call you – are you there? I have returned, I am here again. I have shaken the dust of all the lands from my feet, and I have come to you, I am with you.” In these fateful words lies the central premise behind The Red Book. Swiss psychologist Carl Jung recalls the deep, murky waters he landed upon in his first crack at making contact with the unknown, his ‘soul.’

Though a rambling dialogue with oneself is not the typical image of a psychologist at work, Jung breaks convention in his most prized work. The Red Book’s prose meshes two fields that are seemingly in constant opposition with each other: art and science.

You see, The Red Book is the product of a long, deliberate experiment, one unlike anything done before. In 1913, Jung began employing a technique he called active imagination — a method of creating dialogue with the different parts of the psyche (or mind). It is similar to dreaming, except one is fully awake and conscious during the experience.

In fact, this gives active imagination its distinctive quality — it is a discussion between conscious (known) and unconscious (unknown) elements. Jung believed that an understanding of the ‘inner-world’ (what is inside of us) is vital to the quest for achieving individuation (psychological wholeness), from which one may attain a truer sense of their own personal identity.

However, what happened next to Carl Jung in The Red Book has become the topic of lasting controversy among psychologists and Jungians. In the crucial years from 1913 to 1917, Jung’s mind would be bombarded by haunted visions and chilling inner voices. He recounts having had to “cling to the table so as not to fall apart.” He worried that he was “menaced by a psychosis” or “doing a schizophrenia.” Still, Jung recorded it all, calling this period of his life the “confrontation with the unconscious.”

What Jung experienced was neither psychosis, nor an episode of schizophrenia. The Red Book is so controversial because it touches upon an age-old relic of human life — the soul. Its story is one of great ups-and-downs, one which is told outside of its pages as much as it is told within them. The book is a hefty reflection on Jung’s crisis during his most trying times.

Experiencing Liber Novus

Taken for a moment, The Red Book makes an outstanding presence. Its red, leathery frame beams onto the golden letters of its cover “Liber Novus,” Latin for “New Book.” Opening its thick, oversized parchment, pages are sodden in husky German calligraphy. The characters encountered in this story are strange, always taking place over an ill-defined, peculiar backdrop. A plethora of richly-colored paintings dot the interior, depicting scenes ranging from an enshrined mandala in a deep, cerulean landscape to a black snake rising from the fiery depths. It’s easy to gape at their staggering details.

The Red Book thus presents an unabashedly mind-boggling journey into Jung’s mind, an epic, circular voyage that will send the reader flying from the modest to the absurd, from the dawn of The Bible to an earnest look at Germany during the First World War. The book is by all means a difficult journey, and like many things with Jung, a creative oddity.

Jung continued to write and paint The Red Book between 1913 and 1932 across five small black journals he called The Black Books, and later analyzed them in a magnificent tone between two faces of creamy, red leather. Though its pages abruptly end for unknown reasons, the book would be the muse for a torrent of psychological theories later in Jung’s life. The thick spine of dream-fantasies and otherworldly imaginations excavate the far-reaching depths of the human psyche on live paper.

And yet, for the greater part of the twentieth century, very little was known about The Red Book. When Jung passed away in 1961, it was left unclear what his intentions were for his works. Jung’s oldest son, Franz, kept it where it was in a locked cupboard in his house in the suburbs of Zürich, Switzerland. In 1984, the book would be stowed away in a bank vault, where it lay by a corner since. For the longest time, the Jung household had little idea what to do about the man who became a legend in his own family.

Gated from realizing its own myth, The Red Book harbored adoration and perplexion from miles away. Of the two-dozen people who got ahold of a draft, thoughts and opinions are two-cliffs-and-a-valley-in-between: one Englishwoman insisted it held infinite wisdom, stating “There are people in my country who would read it from cover to cover without stopping to breathe scarcely,” and another, more academic type saw the work of a psychotic.

It was only until the book had been miraculously dug up from the cacophony of papers at Yale University’s Beinecke Library and published in 2009 that it would be called “The most influential unpublished work in the history of psychology” (W.W. Norton & Company). It took nearly a century for The Red Book to take the public stage, but its roots lie even deeper.

The Journey’s Unfolding

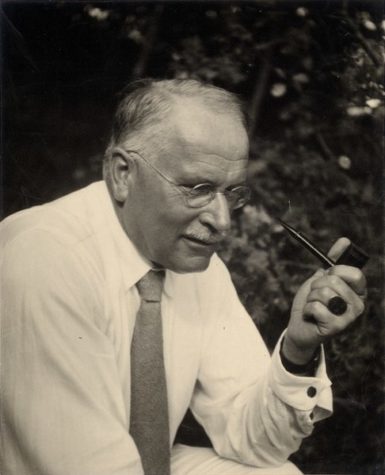

The story begins with the story of its author. Carl Gustav Jung was born in 1875 along the shores of Lake Constance in Kesswil, Switzerland.

Jung grew up as a unique, but lonely child. From time-to-time the boy Carl Jung would present scrolls of a secret language he developed to a mannequin in his attic. He’d also sit on a rock in his garden and begin playing mind games, “Am I the one who is sitting on the stone, or am I the stone on which he is sitting?” Here, Jung dabbled himself into psychological projection, in which somebody mistakes their inner thoughts for the outer objects around them. Jung would continue along this path of intense curiosity into his adulthood.

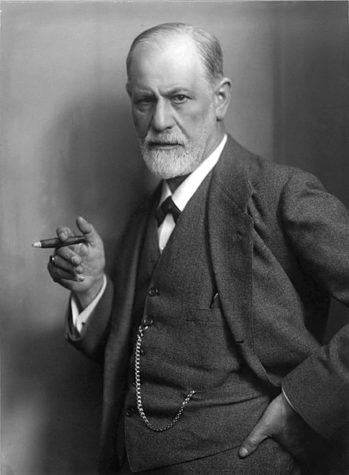

In 1907, Jung, now a professional psychiatrist in clinical practice in Vienna, became acquainted with Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis and soon-to-be face of modern psychology. Jung and Freud’s subsequent friendship took off — it is said that upon their first meeting, Jung and Freud talked for over thirteen hours straight.

First student-mentor, then rivals and collaborators, the two are credited with “popularizing the idea that a person’s interior life merited not just attention but dedicated exploration,” as Sara Corbett discusses in her New York Times article ‘The Holy Grail of the Unconscious.’ With the successes of Jung and Freud, mental health became a recognized part of the individual’s wellbeing in society.

But as time went on, Jung’s and Freud’s theories would go their separate ways. Soon, an idea would be as deadly as poison to their friendship.

Disputes began with Freud’s theory of the Oedipal complex, a condition which correlated the Greek mythological story of Oedipus — who is known to have killed his father and then slept with his mother — to a subdued incestuous desire present within humans. Jung found this outrageous, instead contending that sexuality is not always the motive of the unconscious.

The two sparred back and forth for months, but what their friction ultimately reveals is the disparity molded between two different notions of what the unconscious is.

Freud saw the unconscious side of humanity as a morass of repressed desires accumulated through the course of life — an empty dustbin to be filled from birth. He firmly believed that the mind can only be understood through definite, scientific means. Notably, Freud denied the notion of the psyche having its own free-will or direction. According to him, the mind begins as a tabula rasa, Latin for ‘blank slate.’

This contrasts with Jung, whose bohemian studies into the ramblings of schizophrenic patients, séances, spirits and anomalies, into culture, religion, philosophy and mythology inspired a unique perspective. What Jung ended up with in the soup of his work was an unconscious that is far more of a fluid, spiritual place.

To Jung, dreams and imaginations offer a rich and symbolic narrative coming from the depths of the psyche. He believed that the unconscious mind is a teeming hotbed for all the potentialities within a person. As such, the unconscious takes on colossal proportions. Jung compares the conscious world — including everything that we can see, feel, or understand on a day-to-day basis — to that of a needle-in-a-haystack, “The sea is the favorite symbol for the unconscious, the mother of all that lives.”

However, Jung’s newfound enthusiasm for the unexplainable did not sit well with the skeptical Freud, and neither did Freud’s limited and overly negative view of the unconscious sit well with the ambitious Jung; things came to a head when their differences became the bane of their friendship.

Taking On The Deep-End

The tragic result of their split was Jung’s swift descent into terror. He remembers having experienced visions of a Europe beneath “rivers of blood” in his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections. All of a sudden, the unconscious mingled with the conscious. The world had become strange.

At the same time, Jung found the jargon of his psychiatrist peers particularly distressing — the formulaic language of symptom, diagnosis and quick treatment spoken in the chambers of Germany’s asylum wards. Jung no longer considered the Western Enlightenment ideals, which rationalized every condition to a cause-and-effect relationship, to be sufficient.

Rather, Jung felt that it had become deeply inhuman — people were becoming stuck in their logical minds, leaving the worlds of emotion and body to take the pitfall. Modernity had taught the populace that the past was fraught with superstition and backwardness. The dreams, myths and legends which had once sprawled in ancient minds were now subject to doubt and indifference.

The troubling times were slabbed in cement when World War broke out just a year later in 1914. With this, Jung saw a prophetic significance brimming in the unconscious.

At this point in his life, Jung was outwardly a keen and successful man with a cheerful family, a thriving career and a large, elegant house along the shores of Lake Zürich. Despite this, on the inside, his machinations were someplace else — they were calling for his great mission. Sonu Shamdasani, the editor of The Red Book, explains that detachment in an interview, “In 1912 and 1913, Jung went through a moment of deep personal crisis. Looking back on his life, he finds that he has lost the meaning of it.”

As his convictions materialized, Jung realized the long road ahead of him. Though he had been elected president of the International Psychoanalytic Society in 1911, in 1914, Jung resigned.

Still, there was a niche in the field that would accommodate Jung. Psychology in the early twentieth century was in its infantile stages and just learning to stand on its own two feet. Inquiry from curious writers into the research of psychologists resolved to depict the dream-world in novel form.

A cultural movement of intense exploration sprung forth — writers, psychologists, and artists all collaborated and borrowed from each other’s work. The lines between psychology and literature became blurred. German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche warns of the ‘death of God’ in a secularized world in his book Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883); French writer André Breton read the works of numerous psychologists to soon lay the foundations for the 1920s Surrealist art movement, which sought to paint a bridge between the subconscious and reality. Change was on the horizon.

It was this band of flexible thinkers who spurred Jung, in his midlife crisis, to take on the deep-end. At a moment of intimate cultural renewal, Jung entered his ‘afternoon of life’ by writing The Red Book.

“It was a toasty time for psychological thinking,” Lucas Melendez ’23 said. “What we see is that The Red Book predated our common notions of modern psychology, but when you read it, you can see how it all comes together. The language just wasn’t there yet.”

A telltale example of this is found in Jung’s concepts of extraversion and introversion: the former for external-world energy, the latter for inner-world energy. While the words are synonyms for social mobility today, a century ago they expressed something uniquely Jungian.

Nowadays, whether he would have wanted it this way, Jung — who saw himself as a scientist — has become something of a countercultural icon for artists and dreamers far-and-wide, an important guru for those seeking spirituality outside religion. As such, he has met both wide esteem and wide criticism.

Jung’s work has also seeped its way into pop culture and become a motif behind some of the most captivating psychological novels and films, sometimes even unintentionally — Tolkien’s deeply imaginative Lord of the Rings (1954/55), McTeigue’s ideological revolution in the film V for Vendetta (2005), and more recently, Tatsuki Fujimoto’s collective fears of the devils in the manga series Chainsaw Man (2018), to name a few.

Jung stands today somewhere at the fringes of mainstream psychology, though in the decades since his death in 1961, he has been designated a special seat in just about every facet of society — a sentiment that he may stand the test of time.

The Red Book As Magnum Opus

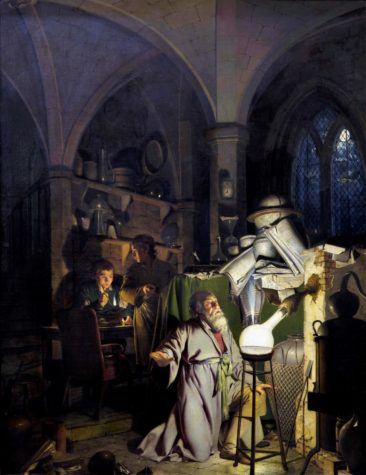

There is no better word for The Red Book as Jung’s focal point in a mandala-esque series of works than magnum opus. Magnum opus — literally meaning ‘Great Work’ — is a Latin alchemical term referring to the process of creating the lapis philosophorum, or Philosopher’s Stone.

To the alchemists, the Philosopher’s Stone was the primary subject of alchemy, believed to enable its wielder the ability to obtain immortality by drinking the Elixir of Life. Over the course of about 2,500 years, the alchemists continually sought after these prizes through concentrated experimentation into the mind and soul. The candle-lit image of a tinkering apprentice at work, fiddling with tinctures, buried beneath piles of paper and grimoires, sketching figures and scribbling notes, performing the enchanted art form of their studies is strong here.

Whether or not the Philosopher’s Stone was ever achieved may never be known. Alchemical practice tragically fell into obscurity with the rise of the modern sciences in the eighteenth century.

However, this does not discredit the alchemists as unsuccessful or a hoax. One of Jung’s great insights was a rejuvenation of the old alchemists from the back of dusty library shelves. He noticed that many of the alchemical symbols in The Secret of the Golden Flower (a Chinese Taoist alchemical book written in the 1690s) were tackling the very same psychological issues he grappled with in The Red Book.

As it turns out, the alchemists were not crazed lunatics in a bunker, but rather the loyal practitioners of an abundance of spiritual-psychological possibilities. The benefits of alchemy were not material gain, but rather psychological gain. It makes us think twice about where we uncover our motives.

Jung’s unfolding curiosity with alchemy would lead him down a lifelong rabbit-hole, studying such areas as the Christian sect of Gnosticism, a mystical take on the orthodox Christian message.

After The Red Book, Jung cultivated a new sense of self, devoting the remainder of his life to the path he forged. Those years spent cooped up in his mind would go on to inspire his most prominent ideas. Soon, Jung would derive the process of individuation — a long development of coming to terms with the conscious and unconscious sides of oneself, in whatever form they might take.

For Jung, his individuation was seen in The Red Book, but for someone else, it will take their unique shape. To those who wish to follow the path of individuation, Jung says to them, “There is only one way and that is your way.”

That isn’t to say that coming to fruition of oneself is by any means a unique idea, as everybody experiences individuation in their own right. Jung was also no stranger to seeing same ideas unravel wherever he went. For him, those inexplicable feelings of connection he felt throughout his life originated in the mind. He called it synchronicity – the occurrence of events that almost seem to open up the world as if it were speaking directly to you.

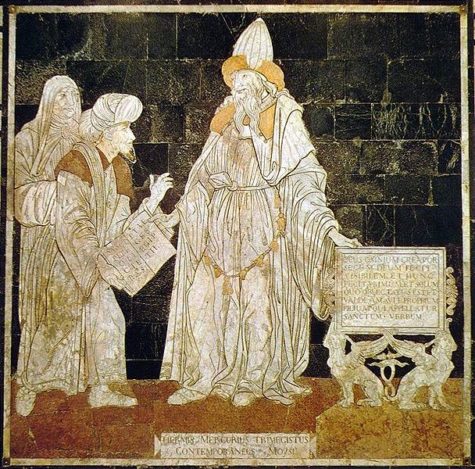

Take, for example, Hermes Trismegistus, an ancient Hellenistic figure of a combination between the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian deity Thoth who laid the foundation for the alchemists and Jungian individuation some two-and-a-half millennia ago: “As above, so below.”

The inner world and the outer world are none without the other; the eternal realm of the inner parallels the bodily realm of the outer. When we transform, we transform the world, we transform ourselves. We see that our waters have expanded and embraced the great tide. The cosmic Moon which hangs over us beckons for us, too. As above, so below.

The Red Book is so controversial because it touches upon an age-old relic of human life — the soul. Its story is one of great ups-and-downs, one which is told outside of its pages as much as it is told within them. The book is a hefty reflection on Jung’s crisis during his most trying times.

Rajin Tahsan is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ Rajin enjoys journalistic writing because it enables him to explore fascinating intersections...