Toni Morrison’s Musings on Motherhood: A Review of the Short Story ‘Recitatif’

In ‘Recitatif,’ Toni Morrison investigates the ailments of society, motherhood, and friendship.

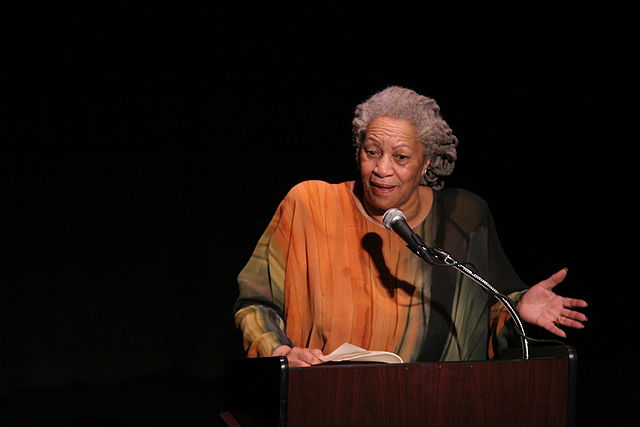

Angela Radulescu, CC BY-SA 2.0

Toni Morrison passed away nearly three years ago and released her last novel seven years ago. However, her work continues to inspire and influence an entire generation, including myself, who gain a different understanding of Blackness, human nature, and power structures, with every re-read of her novels.

Toni Morrison’s novels have explored an impressive array of topics in unique and unprecedented ways. While these topics are extremely vast and nuanced, it may be safe to say that the recurring themes in her writing explore the intersection of two subjects: race and motherhood.

Many of Morrison’s characters could rightfully be considered “bad” mothers. In Beloved, Sethe apparently murders her daughter and tries to kill her other children; in The Bluest Eye, Polly Breedlove continually tolerates her husband’s abusive nature and permits an unsafe and tumultuous environment for her children; in Sula, Hannah and Eva Peace bequeath a dangerous desire to their daughters, producing a cycle that threatens never to break.

While many authors, especially female authors, feel obligated to uphold the narrative of a robotic, flawless and undemanding mother, Morrison wrote about the most horrendous and complicated aspects of motherhood with delicate recognition. These mothers were often consumed by their desires and wanted or took more than what they gave their children. Her examination of race and motherhood is evident in her only short story ‘Recitatif,’ which was originally published in 1983 but recently republished as a standalone novel in February 2022.

Morrison was never afraid to address racism publicly — she constantly challenged her interviewers when they claimed that she wrote “only” about Black characters — and in her fiction writing. Not only did she address race, but she also explored how it exists alongside — and can clash with — gender, poverty, and religion.

One of the most fascinating aspects of ‘Recitatif’ is Morrison’s withdrawal of the characters’ racial identities, including the two main characters: Twyla and Roberta, two girls who meet in an orphanage named St. Bonaventure, after the Italian philosopher who overcame illness as a child and became a religious scholar. The girls bond over being the only two pupils in the orphanage whose parents are still alive. Twyla takes pride in this, momentarily believing that “A pretty mother on earth is better than a beautiful dead one in the sky even if she did leave you all alone to go dancing.”

There is one place the reader will believe that they have found the answer to which character is which race — by comparing the behaviors of Twyla’s mother to Roberta’s mother and, eventually, the mothering practices of Twyla and Roberta.

We are introduced to the characters by their descriptions of their mothers. The story begins with Twyla narrating, “My mother danced all night and Roberta’s was sick.” The first statement she makes is, “My mother wouldn’t like you putting me here” when Mrs. Itkin, whom the characters call “Big Bozo,” rooms her with Roberta. She cites the reason for her mother’s potential disapproval to be that Roberta is of a different race than her. Roberta is oblivious to Twyla’s decree and attempts to converse with her, asking “Is your mother sick too?”

Their mothers’ distinct personalities are on full display during an afternoon visit. Twyla’s mother, Mary, whom Twyla calls by her first name, arrives glamorously, whereas Roberta’s mother is modest and reserved, refusing to shake Mary’s hand. Twyla is embarrassed by Mary and her behavior during the sermon. From the narration, we can see that Twyla has been forced into independence and maturity because of Mary’s irresponsible nature. But Roberta also has that same mature nature despite having a relatively responsible mother.

As grown women, both characters are immensely imperfect, especially in their mothering. In the middle of ‘Recitatif,’ we are reintroduced to Twyla and Roberta as mothers, Twyla with her teenage son and Roberta with her four step-children. The two mothers have a fierce and mostly non-verbal argument regarding school integration. Continuing with her mission to seal the races of the characters, Morrison never explicitly stated who supports integration and who supports segregation.

Both mothers “protest.” However, they are trying to compete with one another rather than passionately taking a stance. The posters that they make are practically incoherent as they are responding to one another instead of addressing integration. Twyla narrates, “Actually my sign didn’t make sense without Roberta’s. ‘And so do children what?’ one of the women on my side asked me. Have rights, I said, as though it was obvious.” Twyla decides the best way to target Roberta is by mentioning her mother, so she creates “a painted sign in queenly red with huge black letters that said, IS YOUR MOTHER WELL?” referencing that Roberta was placed in the orphanage because her mother was too ill to care for her.

The women reunite once again at the conclusion of the story. During this unplanned reunion the paranoia surrounding the desire to know one’s race is reflected in the characters’ battle to determine the race of Maggie, the nonverbal and disabled cleaning lady at the orphanage. When she was a child, Twyla believed Maggie was white. In the midst of the integration dispute, Roberta claims that Maggie was a Black woman. The integrity of this revelation is unclear but it still haunts Twyla, who begins to question her entire childhood and even wonders if Maggie was her mother.

‘Recitatif’ offers a deep reflection on how we assign certain features to a race and why that process of assignment is detrimental. Some Americans would believe that this reflection is unnecessary, under the belief that America is an uncorrupt post-racial society that has reckoned with centuries of legalized anti-Blackness.

With the short story’s omission of race, Morrison wasn’t trying to assert that “kids don’t see race” or fuel race-blind attitudes. Morrison had always vocalized that race is central to a child’s perception of their world and themselves. Most notably in her novels, God Help the Child and The Bluest Eye, she investigates how societal preferences for white or light-skinned children cause dark-skinned children to feel an intense and relentless level of alienation. This goes on to shape the way they interact — or don’t interact — with the racialized world around them. In these novels and in the real world, the adoration of pale skin is upheld across all races.

There is a lot for which to thank Toni Morrison. She established an environment that encouraged artists to depict the concealed and dismissed aspects of society with integrity and courage. Writers including Ocean Vuong, Tarell Alvin McCraney, and Zadie Smith have all been stimulated by this environment. Smith, the Jamaican-British novelist of White Teeth and Swing Time wrote the introduction for ‘Recitatif.’ In her introduction she wrote, “That people live and die within a specific history — within deeply embedded cultural, racial, and class codes — is a reality that cannot be denied, and often a beautiful one.”

Morrison lived within a history that wanted to sanitize Black art, and it would have been easy to let the pressures of the predominantly white literary world transform her writing. But she conquered those pressures and, in the process, changed history.

While many authors, especially female authors, feel obligated to uphold the narrative of a robotic, flawless and undemanding mother, Morrison wrote about the most horrendous and complicated aspects of motherhood with delicate recognition.

Aissata Barry is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She believes that journalism is appealing because it creates a fascinating connection between...