Hans Holbein as a Humanist Hero in an Exhibition at the Morgan Library

Renaissance art, characterized by its striking realism and secular scenes, sharply contrasts the darkness of the Baroque works that followed. Despite such distinctions, the Morgan Library’s Hans Holbein exhibition transitions seamlessly between the two.

Simon George poses with a lucious, bright red carnation (Simon George).

Amidst a whirlwind of divine divisions, Martin Luther’s “The Ninety-five Theses” catalyzed growing discontent within the Christian church. It set off a robust religious movement, owing to the radical writings of the theological treatise. The emergent Protestant faith encouraged, most notably, a turn against iconography. Though tumultuous, the resulting strife yielded a cornucopia of artistic potential.

The cornucopia’s sweetest fruit was, arguably, Hans Holbein. Born in 1497, the German artist was raised by a family of painters who exposed him to a climate of creativity from a young age. His father, Hans Holbein the Elder, was acclaimed for his depictions of Gothic motifs. Ambrosius Holbein, older brother to Hans, opted for a similar path.

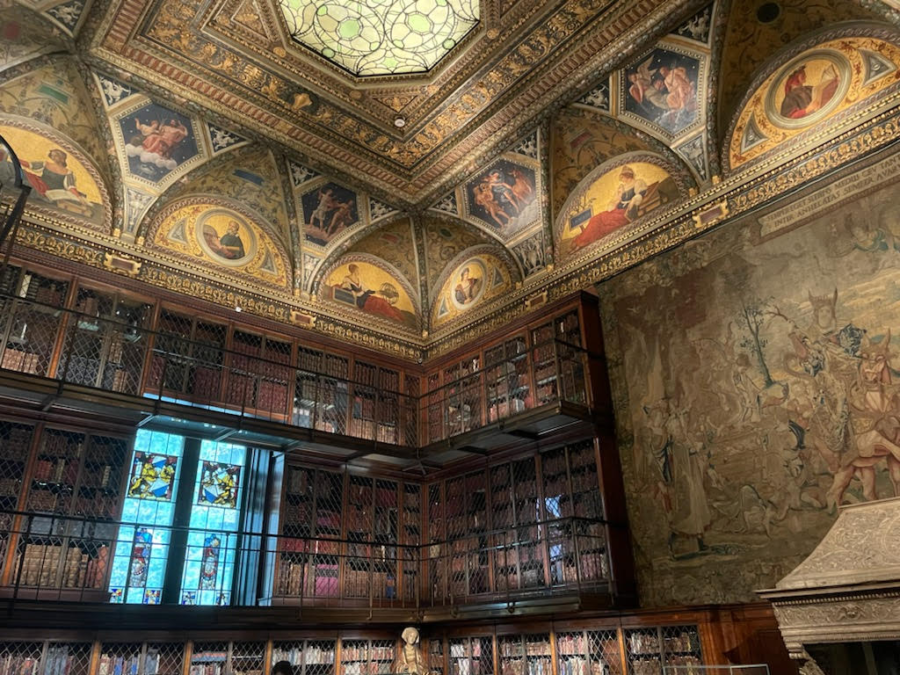

Holbein’s work can be viewed currently in the ‘Holbein: Capturing Character’ exhibition, which is open at the Morgan Library (225 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016), through May 15th, 2022.

Beyond his familial influence, the painter utilized those before him as muses, soon reaching pictorial perfection. Hans Holbein looked to Albrecht Dürer and Jan van Eyck, for example, as aesthetic inspiration. The former pioneered the self-portrait, utilizing lighting to underscore a realist style, in turn paving the way for Holbein’s prized portraiture.

The latter employed a strategy of oil paints on wood and ubiquitous symbolism just as Holbein would, incorporating camouflaged memoranda into pieces including the famed Arnolfini Portrait. “To a certain extent,” said Katia Anastas ’23, “artistic originality is a myth. Every artist, no matter the time period, is influenced by the works of previous artists and by their external circumstances.”

Holbein then embarked on a journey westward, working out of Switzerland for some time. Through his work, he would encounter Dutch philosopher Desiderius Erasmus, by means of which Holbein cultivated a myriad of connections to wealthy English officials.

The thinker’s influence proved widespread; Erasmus was the first celebrity scholar, widely recognized throughout Europe. The then recently invented printing press enabled a vast distribution of Erasmus’s theological writings, with opuses such as Praise of Folly and Moriae Encomium read by constituents of all social classes.

Erasmus transitively provided Holbein with ample publicity, setting the artist’s career into coursing motion. He chose to follow the demand for his artistic genius, traveling through Antwerp, Belgium to permanently station himself in England. This endorsement, however, was not a one-way street. Erasmus used trademark insignias and portraits alongside his writing in order to further his influence.

He developed a personal symbol: Terminus, the Roman god of boundaries. Renowned for resisting Jupiter, the king of gods, association with Terminus gave Erasmus an element of strength and credibility to his name.

The “emblems were chosen to reflect some aspect of the sitter’s character or personality…no different than today when we choose a specific piece of clothing or background to say something about ourselves in a selfie,” said John McQuillen, curator at the Morgan Library. Holbein therefore depicted Terminus and Erasmus as a pair in his work, illustrating his sitter with a stoic expression akin to that in sculptures of the Roman deity.

Further mirroring Roman tradition, Holbein strays from idealism — as found in ancient Greece — and retains a potent element of realism in Erasmus of Rotterdam. The small, round portrait was fabricated in 1523 as a gift to the scholar’s godson. He is portrayed as elderly, with sunken cheeks and wrinkled skin.

Such features are not prized today, but they were seen as signs of wisdom in ancient Rome. Erasmus’s erudition is further denoted within his attire. He dons a modest black hat and robe, which contribute to the portrait’s dark, solemn tone.

Device of Erasmus, crafted in the same year, amalgamates the man with his signature symbol. Holbein draws Terminus with the facial features of Erasmus, morphing their appearances into one visage. Viewers observe the scene through a stone opening, avoiding eye contact with the painting’s subject as the now holy Erasmus gazes across an unadorned landscape.

Behind his head lies a golden disk, symbolic of divine radiance. It underscores the Christian virtues within Erasmus’s emblem: steadfast character and faith. This generous representation is rare for its time, indicating that it was meant to please viewers as opposed to Erasmus.

The scholar eventually passed away in 1536, a solemn event commemorated by the portrait Erasmus of Rotterdam (im Gehäus). Incongruous with Holbein’s previous paintings, this work is a full body portrait in which Erasmus dons long robes. He stands before a sumptuously decorated arch, adorned with wreaths and baskets which allude to his prolific wisdom.

The intellect is shown with one hand on a herm (stone sculpture of a head and torso) of Terminus, who casts a shrewd glance at onlookers. Underneath the lavish image is a Latin inscription, which reads “If you have not seen Erasmus in life, then this image, executed from life, will show you how he looked.”

Prior to his passing, Erasmus introduced Holbein to a second loyal patron: his printer, Johann Froben. The publisher hailed from Basel, Switzerland, and merited a portrait of his own. Holbein painted Johann Froben around 1528, initially encasing the piece with a lid and engraved frame. The work represents one of the first known depictions of a book printer, rendering Froben a linchpin for the intersection of art and print.

Apart from portraiture, Holbein worked in partnership with Froben to design woodcut illustrations for a plethora of publications, including Hieroglyphica by Horapollo, originally written in the fourth century.

Pharaonic scribes narrate the world’s natural and moral evolution through allegorical symbols in the work, which couple concurrently with Holbein’s imagery, crafted to appear classically cultured. While his contributions are denoted by the minuscule letters “HH” along the book’s left border, Froben is commemorated by his printer’s mark: the caduceus of Mercury, the Roman god of commerce.

The pair continued their collaboration in the publication of the rather succinctly named Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Martin Lutherum (Assertion of the seven sacraments in opposition to Martin Luther). Though neither Froben nor Holbein wrote the piece, it involved them in the civic animosity of their time.

Bronx Science history teacher Mr. Frederic Schorr considers this piece to be part of a larger trend, where political climates influence art “significantly. But,” he said, “it all depends on the individual artist. To what degree are they thinking politically?” To Holbein, this degree was great.

Perhaps the greatest induction of Holbein’s governmental interconnection was King Henry VIII. Holbein acquired a wealthy clientele at the royal court, among which were the king’s personnel. He painted the pair of Portrait of a Court Official of Henry VIII and Portrait of a Woman in the service of Henry VIII in 1534, traditional to Holbein’s style in their minimal size and meticulous detail.

The man dons a royal, red livery, with initials HR for Henricus Rex (King Henry VIII) etched into the fabric, while his female counterpart wears unassuming clothing. Holbein uses this to underscore the intricacies of the image’s various textures, from the fur trimmings of her velvet dress to the wool of her bonnet.

A second woman under the king warranted a portrait: one hypothesized to be Anne Lovell, whose husband served Henry VIII. A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, painted in roughly 1526, utilizes motifs of flora and fauna to reference the noblewoman’s relatives. The work features a red squirrel, found thrice throughout the Lovell family crest.

Behind the woman lies a starling, a reference to East Harling (spelled Estharlyng in the Tudor epoch), her residency in Norfolk, England. The creatures were not added until after Holbein finished the portrait, indicating their significance to those who commissioned the painting.

Symbolism plays a further decisive role in Mary, Lady Guildford, dated 1527. The piece is unique in its portrayal of Mary, who stares directly at the viewer as opposed to the majority of Holbein’s sitters who gaze obliquely to the side. John McQuillen explains that it is “unusual for a woman to be so direct. She really grabs, almost demands, your attention.”

The oeuvre is rife with symbolism, communicating a religious undertone. Mary holds a rosary in one hand, as if caught mid-prayer, and wears a sprig of rosemary on her dress. The herb is emblematic of remembrance, depicting Mary, Lady Guildford as demure and devout.

Her piety and virtue are further emphasized by the sophistication of the portrait’s background. Holbein paints both Mary’s dress and the intricate column behind her with gold highlights, an evident indication of stature.

The most prominent reference to religion, however, lies within the book Mary is holding. The Myrroure of the Blessyd Lyf of Jhesu Cryste, written by Johann de Caulibus in 1376, evokes thoughts of mortality, prompting reflection just as a “myrroure” (mirror) would. In Mary, Lady Guildford, Holbein labels the opus using its Latin name: Vita Christi, or Life of Christ. The book indicated “that [Mary] was literate,” said McQuillen, “which was also not common for women in the period.”

Though the pious elements of select pieces were, quite literally, spelled out, Holbein disguises many other motifs. In his piece Sir Thomas More (1527), for one, More sports an elaborate chain of gold “S’s,” which stand for the French phrase “souvent me souvient” (remember me often). The letters are joined by a Tudor rose at the necklace’s center, presenting a heraldic, English symbol of More’s status.

Such illustration of rank was an essential facet of the portrait, as it was painted at the crest of More’s political career. The work was commissioned just before he was promoted to the highest position of power in Tudor England: lord chancellor, a political shift which greatly influenced the way Holbein portrayed the official. Consequently, he forsook More’s identity as a skillful scholar, instead painting him as an authoritative politician.

Behind More is a lustrous, green curtain, which reappears a decade later in Derick Berck of Cologne, finished in 1536. Berck is a Hanseatic merchant, participating in a league whose goal was to promote the defense and commercial interests of market towns in the medieval era. Both his name and personalized merchant mark are displayed on a paper in his left hand.

A second paper lies just next to Berck, on which is a passage from the ancient Roman poet Virgil. The writing encourages the merchant, his descendants, and viewers alike to maintain courage in business and in life.

Holbein’s An Allegory of Passion further inspires courage through the lens of romance. Crafted in 1536, the oeuvre discusses the theme of love via a seemingly unrelated horse. The animal strides along the untraditionally lozenge-shaped canvas, symbolic of a lover’s quest which its rider embarks on. His romantic journey is written plainly in Latin: “E cosi desio me mena,” meaning “And so desire carries me along.”

Just as Holbein was able to clearly convey motion and liveliness through the gallop of a horse, he utilizes facial asymmetry to do the same. The painting of A Member of the Wedigh Family (1533) illustrates the sitter with ample realism, highlighting a natural lack of symmetry in his appearance.

“The two sides of the man’s faces do not match,” said Morgan Library curator Austėja Mackelaitė. “The eyes, the eyebrows, even the nostrils are different in terms of size and placement.” The purposeful shunning of idealism is characteristic of Holbein, in turn “imbuing the otherwise inert, motionless likenesses with a sense of animation and presence.”

Nearly a decade later, the artist produced Simon George in 1540. George’s identity remains largely unknown; merely his name and place of origin (Cornwall, England) are understood. The exhibition, however, deduced that he was “a poet conversant in the symbolic language of love,” owing to the sophisticated web of symbols which Holbein spun in the portrait.

George holds a red carnation in his right hand, whose color stipulates its analogous relationship to both Christ’s crucifixion and betrothal. Flowers appear for a second time in his hat, where the pansies which decorate it are comparable to decease.

Though Holbein paid scrupulous attention to these minute details in the predominance of his works, certain sitters wished to remain anonymous and thus requested a lack of identifying attributes.

Portrait of a Hanseatic Merchant, dated 1538, limns the trader in sober clothing, whose black, monochrome nature reveals his membership in the Hanseatic League. Despite its ambiguity, the piece is commemorative of the merchant’s thirty-third birthday — an important date, as it is the age at which Christ was crucified.

Akin in divine significance is the philosophically macabre Dance of Death (1538) series. Throughout the collection, skeletons dance with the living as a reminder of their inescapable, impending end. The pernicious theme was not regarded as such in the Middle Ages; rather, it was appreciated as preparation for a proper Christian passing.

“The series illustrates the ubiquity of death: no one, no matter your social position, is immune,” remarked McQuillen. “The religious nature of the series teaches that you must be constantly ready for death, meaning that one must always be spiritually prepared.” The dance was thus painted onto church walls, funerary murals, and prayer-book illustrations alike.

The practice became increasingly common, prompting Holbein to translate it into a book, The Images of Death, in partnership with Swiss blockcutter Hans Lützelburger. Their creation was revolutionary, catalyzing a shift away from flat, two-dimensional scenes (as commonly found in medieval art) and towards lively, contemporary stills.

In his ritualistic fashion, Holbein used distinct symbols in Dance of Death in order to highlight varying undertones in his series, Images of Death. He depicted individuals in the midst of their quotidian routine, drawing the same skeleton with professions from the clergy to a commoner. The works within the sequence were titled quite redundantly; among them are Death and the Monk, Death and the Priest, and Death and the Doctor.

Though the religious tradition protected the souls of those who are long gone, Holbein’s art ensures that its cultural value is not long gone. His portraits preserve stories of the Middle Ages, hailing Holbein as the hero of humanism.

“To a certain extent,” said Katia Anastas ’23, “artistic originality is a myth. Every artist, no matter the time period, is influenced by the works of previous artists and by their external circumstances.”

Sela Emery is a Copy Chief for 'The Science Survey.' She focuses on art history, covering relevant art pieces and exhibitions with each issue. In addition...