Balletcore: A Curtsy to the Intersections of Ballet and Fashion

The rise of ‘balletcore’ sheds light on the close ties between the spheres of ballet and fashion.

Edgar Degas, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Romantic ideas seen in ballet reflected many traditionally female qualities; women were portrayed as virginal, ethereal, and as part of a fantastical world.

With the rise and fall of fashion subgenres in the age of ‘fast fashion,’ it is no surprise balletcore has gained considerable popularity. Characterized by leotards, wrap tie skirts, flared leggings, and ballet flats in a variety of pastel hues, the aesthetic is a form of escapism to the life of an off-duty Parisian ballerina.

Ballet was born during the Italian Renaissance, the introductory phase of the greater European Renaissance. The Renaissance period represented the transition from medieval to early modern Europe – the ‘rebirth’ marked a renewed fervor in classical antiquity following the Dark Ages. Peace and economic prosperity on the European continent beckoned a flourishing humanities and arts scene, which was facilitated by patrons such as the Medici family.

The movement of ballet from its home in Italy to France is attributed to Catherine de Medici, an Italian noblewoman. Following her marriage to King Henry II of France, Catherine de Medici funded ballet in the French court. Her extravagant festivals promoted the growth of ballet de cour (court ballet), which were aristocratic spectacles that included dance, costumes, decor, music, and poetry. The ballet de cour was directed by a dancing master who taught the court the ballet step; ergo, the nobility were members of both the cast and audience of the event.

Ballet de cour reached its apotheosis under the absolute monarch Louis XIV of France. Almost a century after Catherine de Medici, Louis XIV would popularize the aristocratic pastime in his own court. In his grandeur Palace of Versailles, King Louis would wholly embrace ballet de cour by performing many of the roles himself. The dancing monarch was famously coined ‘The Sun King’ following his performance in Le Ballet de la Nuit (1653), an event that ran from sunset to sunrise. His dance master, Pierre Beauchamp, choreographed many of the dances performed at Versailles and is often credited with codifying ballet as a system of movement. Louis XIV later founded the Academie d’Opera in 1669 which developed ballet as a profession and served as a forerunner to the Paris Opera Ballet.

Prior to the nineteenth century, ballet was largely performed by aristocratic men. Women only became the majority of ballet dancers following the Romantic movement which embraced individuality, imagination and beauty over reason. The Romantic ideas seen in ballet reflected many traditionally female qualities; women were portrayed as virginal, ethereal, and part of a fantastical world, while men were tethered to reality. At this time, it became socially unacceptable for men to participate in dance, so they remained behind the scenes as playwrights and dance masters.

Thus, ballet dancers became the pinnacle of femininity, grace, and elegance – a reputation that was only emphasized by their attire.

The most venerated ballerina of the Romantic period was Marie Taglioni, whose femininity and talent earned her droves of fans. Her performance in the play La Sylphide in 1832 at the Paris Opera House was a seminal performance not only in ballet but also fashion. Taglioni’s costume consisted of a white fitted bodice and a translucent, feathery, calf-length tulle skirt. Her feet bore white satin pumps laced around the calf, which was reflective of fashionable evening wear of the time period.

(Eduard Kaiser (1820-1895), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Taglioni’s costume would become the conventional standard for other Romantic ballerinas of her time with minor adjustments. One can trace the influence of La Sylphide in modern dramatic wedding gowns. Major couture powerhouses such as Valentino and Giambattista Valli are well known for their feminine, feathery silk gowns in pastel shades that similarly emphasize the waist.

During World War II, American designer Claire McCardell popularized the classical ballet look among the general public. As materials were scarce from war overseas, McCardell highlighted the versatility of the ballet flat as public street wear. This trend is promoted today by domineering brands in the balletcore community like Repetto, who sell luxury ballet foot wear to both dancers and ordinary people alike.

The twentieth century would diverge from what was known to be classical ballet.

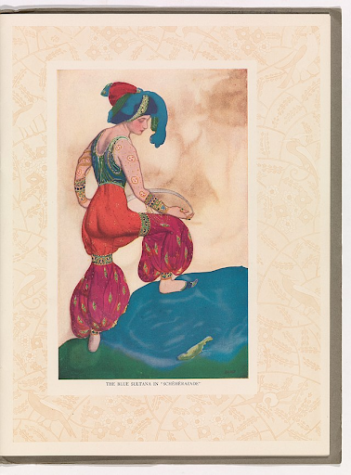

Sergei Diaghilev’s establishment of the Ballet Russes dance company in 1909 fueled the love affair between ballet and fashion. The success of the ballet troupe is closely intertwined with its revolutionary fashion collaborations: Paul Poiret, Leon Bakst, Coco Chanel, and Giorgio de Chirico. The Russian ballet dancers offered Parisian couturiers a taste of Eastern European culture – pre-war designers such as Paul Poiret curated harem skirts and trousers embedded with bold, jewel-like colors.

(Metropolitan Museum of Art / Léon Bakst, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The restaging of ballet classics such as Diaghilev’s The Sleeping Beauty (1920) would revitalize couture’s interest in the aesthetic of ballet. In fact, Vogue’s 1932 issue featured eight pages worth of coverage on the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo’s production of Cotillon that highlighted the costume designs of French artist Christian Berard. Berard was a major figure in the realm of fashion; he was a mentor to designer Christian Dior, who is renowned for his classical-ballet-inspired fashion that dominated French couture in the fifties and sixties.

Christian Dior was yet another familiar face in both fashion and ballet. His ballet-inspired “New Look” reintroduced luxury fashion to women following World War II. After years of championing industrial work at the warfront in functional clothing, women were undoubtedly drawn to Dior’s new portrait of the female silhouette. The “New Look” included hand-span waistlines and bouffant Romantic-length skirts, which paid homage to bodices of the ballet Renaissance courts and Romantic-era tutus.

Popular ballerinas flocked to Christian Dior as he bridged the small chasm between couture and ballet. Margot Fonteyn, an English ballerina most often credited for placing British ballet on the international stage, was one of the many ballerinas who remained loyal to Dior’s elegant, Romantic Era creations.

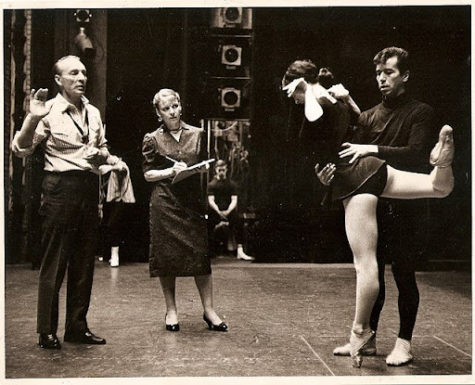

In New York City, ballet choreographer George Balanchine pioneered the shift from extravagance to costumes that prioritized movement. In his “Black and White” ballets, Balanchine embraced minimalism with black belts that emphasized the waist, and slim fitting, diaphanous dresses.

Leotards would become a staple in minimalistic ballet fashion. In the 1970s and 80s popular designers such as Calvin Klein and Donna Karan popularized leotards as acceptable everyday wear for the larger populace.

Today, a multitude of diverse fashion designers indulge in ballet-inspired fashion. Christian Lacroix, Vivenne Westwood, and Viktor and Rolf have contributed their own unique styles to the years of ballet fashion established by their couture predecessors. Since 2012, the New York City Ballet has teamed choreographers with fashion designers for their annual autumn gala.

(CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

TikTok’s balletcore aesthetic is a curtsy to the enduring relationship between fashion and ballet.

American stylist Madeline Jones sees balletcore as “the natural evolution from athleisure.” The athleisure movement, as popularized by brands like Lululemon and Patagonia, receives a feminine makeover from balletcore. It’s the idea of being comfortable in a fashionable, feminine way that has placed balletcore in the spotlight of fashion.

Kanae Funabiki ’23, a ballet dancer with fourteen years of experience under her belt, has nothing but positive impressions about balletcore. “I think it’s really interesting seeing people implement clothing styles used in ballet into fashion,” said Funabiki.

In her ballet form, you can find Funabiki wearing balletcore staples such as leotards, tights, and leggings. For her, these pieces are only worn when she is to dance. “I personally would never mix in my ballet styles because it would just simply feel strange, but I love the creativity of some outfits that people pull off with the balletcore aesthetic.”

While some people in the ballet community find the aestheticization of ballet to be degrading, Funabiki embraces it. “I learned to take it as a compliment since a ballerina’s goal is to make themselves look elegant on stage.” However, it was not always this way. When Funabiki was younger, she found herself disillusioned with the lack of appreciation of ballet as a strenuous sport. “I didn’t believe people understood the amount of intensity, pain, stress, and struggle ballet dancers were put through from a young age.” Critics of the appropriation of ballet fashion in the hands of uninformed consumers include ballet dancer, choreographer, and dance historian Judith Chazin-Bennhum: “Wearing a tutu [signifies] that the dancer had trained vigorously and seriously in order to perform the romantic and classical repertoire.” Debate as to whether placing a tutu on children is depreciating towards ballet as a serious artform continues even today.

With the rise of balletcore, people flock to the aesthetics of ballet and neglect the skill and training required of real ballet dancers. The over aestheticization of ballet is even more concerning as it revolves around the notorious slim female silhouette. Funabiki finds the emphasis on the way one must look as a ballet dancer to be detrimental to their health. “Because there is an ‘ideal body type’ and an ideal way for your body to look on stage, dancers tend to push their bodies to the max and end up constantly injuring themselves. It also contributes to severe body dysmorphia and eating disorders for many ballerinas at a young age.”

Despite this, Funabiki encourages those from the balletcore community to pursue ballet for both its physical benefits and for a tight knit community. “Because dancers are put through such strenuous lessons together, it leads to strong bonds and a sense of family with one another. Other ballet dancers become your best friends and the dance teacher becomes your second mother.”

“I think it’s really interesting seeing people implement clothing styles used in ballet into fashion,” said ballerina Kanae Funabiki ’23.

Karishma Ramkarran is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. She appreciates journalistic...