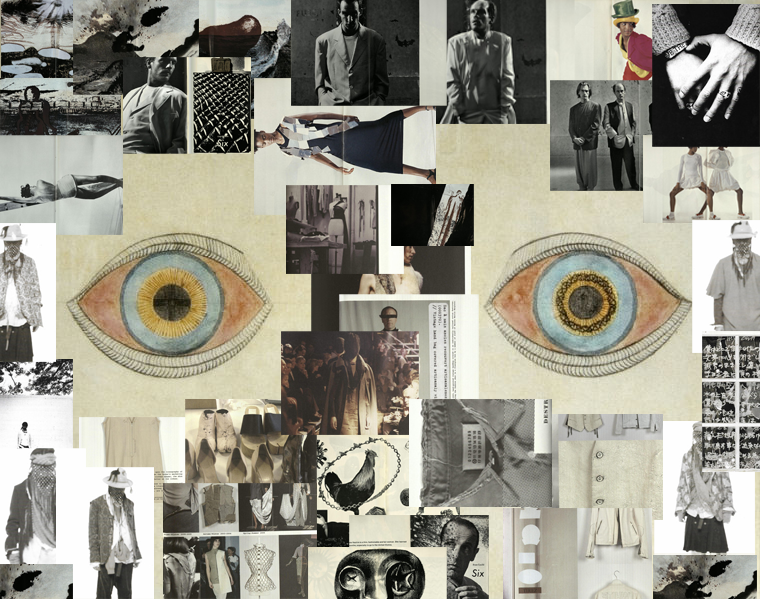

The Slow Cancellation of Fashion

Fashion under late-stage capitalism has become unrecognizable as an artistic form but rather exists in subservience to the mode of production.

{{PD-US}} , archivepdf, Rahib Taher

“Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie maker; but the living flesh it converts into dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us.” – Mark Fisher

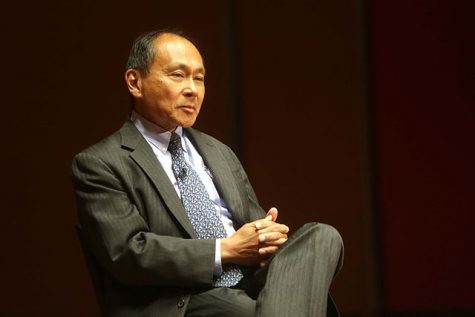

The fall of the Berlin Wall marked what political scientist Francis Fukuyama called ‘The End of History.’ People could no longer dream or think about progressing past neoliberal capitalism and the systems that came with it. Simply, speaking, we had reached our ideological peak. Challengers of this system would be left in the dust, eradicating the existence of the opposition. What we have now, liberal democracy, is the only viable system, and we cannot try anything else due to the looming risk of failure.

A Hauntological Introduction

For Marxists like Frederic Jameson, Slavoj Žižek, and Mark Fisher, this idea is instrumental to their analysis of late stage capitalism. Mark Fisher uses Fukuyama’s ideas as a basis for his own understanding of the era in which we live. He calls it capitalist realism, which stems from Fukuyama’s notion of society’s belief that capitalism is the only feasible economic system and adds that it is not possible for society to imagine an alternative. Fisher believes that there is a way for us to accelerate past capitalism, but he sees capitalist realism as our biggest obstacle.

Mark Fisher’s most interesting criticism is that of the cultural logic of this capitalist realist era. Fisher accredits the development of capitalist realism to the widespread effects that neoliberalism has had on society, including its influence on popular culture, work-life relationships, mental health, and the environment.

In formulating this critique, Fisher draws from the ideas in Jacques Derrida’s book Specters of Marx. Derrida disagrees with Fukuyama in that he does not believe that we have reached the end of history or that Marxism is finished. Instead, Derrida believes that the entity of Marx lives on as a specter, one that is divorced from the past of Marxism yet still echoes its ideas. Derrida defines this as hauntology: the specters of something can still find its place in contemporary society past the point that it has been deemed to be over. It exists in a state of limbo, both existing and not existing at the same time, not unlike the life of Schrodinger’s cat.

Hauntology has become the basis for Fisher’s cultural critiques, which focuses on the evolution of music. Fisher argues that we have approached the end of history, we have been in a constant state of cultural rehash, and the specters of the music from the past haunt today’s music. Fisher cites bands like the Arctic Monkeys as culprits of the influence of the specter. Not only do we find this influence in music but also in all other forms of popular media. In movies, it has been the trend to reboot every single franchise from the past, such as Ghostbusters or Star Wars. The same is true in comics and TV shows, given that rehashes have been the dominant trend of our times.

It is important to mention that Fisher does not believe that every single modern work of music follows the trend of hauntology. In fact, he viewed artists such as Kanye West as able to push the envelope and accelerate culture. He believed, however, that this was what popular culture had truly become and that capitalism had reinforced such a structural trend. Subsequently, it also did the same in other aspects of the world we live in including that of politics.

The cultural and political worlds of our era are interconnected and follow the pessimism of Fukuyama’s words. In politics, we have been stuck in a deadlock. The quarrels between the two parties in the United States can be best described as a game of tug of war where both sides are pulling, yet the rope remains in the same place. There is no definite leftward or rightward turn from neoliberalism that we can see or even imagine from a system. The same idea applies to the way the future of culture is in a deadlock, where popular culture is dominated by the specters of the past. This is an idea that Fisher refers to as the cancellation of the future. Everything that we envision in the present is in some way tied to the past. The new, if ever conceived, is small in comparison to the rest of the haunted subjects. A future, which I would define as a drastic change from the past, cannot actually exist because of the grand influence of the past that creates the repetitive structures of the present.

It is not to say that any of the art that has been haunted by the past is necessarily bad, as there are lots of haunted works that are enjoyable. Rather, Fisher is asking what it says about our society that we cannot imagine a future and must rely on past cultural forms to construct our present. We are intoxicated with the past cultural forms, to the point that we are only interested in consumption in the present and are not worried about the consequences that such a consumption may have on our future. In this case there does not seem to be any cultural future or the cultural future is clouded by our current interests.

Popular Fashion and Conformity

But what if anything does this have to do with fashion? Fashion is yet another cultural medium that has become haunted. In both the contemporary popular fashion and the high fashion spheres, we are able to observe a rehashing of old forms.

Understanding the state of popular fashion involves understanding the nature of consumption. Consumption in today’s world is dominated by the principles of instant gratification, and the current composition of the contemporary fashion industry caters to this principle. Fast fashion, including but not limited to Forever 21, Shein and Fashion Nova, are all culprits of such behavior and even beyond that, there are options that are a little more expensive yet still perpetuate the same type of consumption.

Our need to consume in such a manner relates both to the way in which neoliberalism as an economic system promotes the growth of fast fashion firms as well as the prestige or the conformity that commodities afford us. The latter idea is known as the sign value and is an extension of Marx’s theories on value as formulated by the sociologist Jean Baudrillard.

The sign value is the value extracted from a commodity like a piece of clothing based on its ability to provide the owner with some social value. Our desire to conform to the social standards of the time we live in is the driving force in the trends of consumption. Overconsumption thus in turn reinforces the hauntological trends observed in fashion today because it is the social standard or that to which we should conform.

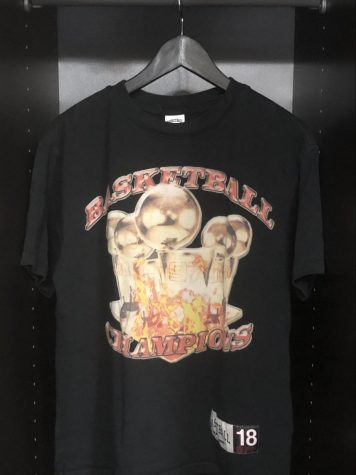

Popular fashion is obsessed with the vintage and with the old eras of fashion, times that the youth of today have not experienced but yet still make up much of their current reality. From old faded vintage t-shirts that are printed with the images of brands and icons from long ago to trends that existed in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, fashion is obsessed with the hauntological.

Trends of consumption such as fast fashion and the concept of sign value work in a feedback loop to maintain popular fashion culture, a fashion culture that is haunted.

Let us look at a contemporary case for an easier understanding. For example, you cannot go to an H&M or a Forever 21 store without seeing a fake vintage item that they have created. What is meant by fake vintage is a piece of clothing that they have created which reflects the cultural trends of a time from the past. These items are usually less than ten dollars, and they are made to be affordable so that more can be purchased. They are purchased because they help the wearer feel some social validation rather than blatant self expression. Due to these factors, they continue to be consumed and also continue to grow as the standard for conformity which causes even more consumption. Haunted clothing, then becomes the image for popular fashion culture.

Raf Simons and the Commodified Riot

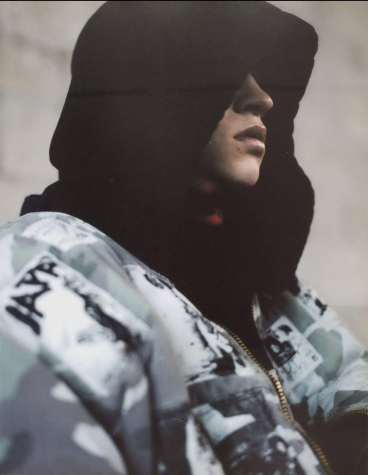

This trend does not only manifest itself in popular fashion but also in high fashion. Raf Simons, whose popularity has drastically increased in recent times because of his label’s association with popular rappers like A$AP Rocky, is another symptom of hauntology. The sign value surrounding his work has been significantly boosted through its association with hip hop culture, now being sold for tens of thousands per piece.

His most iconic collection is probably 2001’s “RIOT! RIOT! RIOT!”, where a particular bomber jacket ended up selling for $47,000 on the clothing auction website grailed. What’s interesting about “RIOT! RIOT! RIOT!” in particular is that it was a collection based around documenting the cultural aesthetics of the period right after the fall of the Soviet Union. Specifically, it focused on the youth counterculture that appeared during a decade filled with military intervention and political instability as well as an awkward transition into neoliberalism that manifested itself into the riot of the youth.

Raf also hid references to bands like Joy Division and Sonic Youth in the patches attached to the militaristic clothing. He wanted to highlight the suffering that often went into creating art or performing art in this case. Raf wanted to capture the spirit of riot in every single way that he could, in the cries of the Eastern European youth. You can view the original recording of the show here.

Today however, the meaning behind Raf’s pieces from this collection are merely reduced to spectacle. For the most part, those who purchase them are doing so for the sign value that they bring — everyone from Kanye West to Travis Scott to Drake has been seen wearing the jacket — the prestige that it awards is beyond comprehension. Raf recently re-released many pieces from this particular collection in a collection of all of his greatest hit pieces called Raf Simons Archive Redux. What is most depressing about the hauntological re-emergence of these pieces into the world of today is that their original meanings of unfiltered riot is erased by the new meaning placed upon them by the obsession with their sign value. The riot of yesteryear is recycled into the present but does not accomplish anything in creating a vision of the future; rather it contributes to its distortion and cancellation. The lookbook for the Redux collection can be viewed here.

While stories like Raf’s may be a bit dispiriting, there are other means in which hauntology manifests itself into high fashion. The hauntology of Raf was based on a popular re-emergence and hyper commodification of his work, while the hauntology in the work of someone like Jun Takahashi of Undercover manifests into design. One of my favorite works of Takahashi is his Spring Summer 2011 collection entitled “UNDERMAN.”

Jun Takahashi and the Lost Future

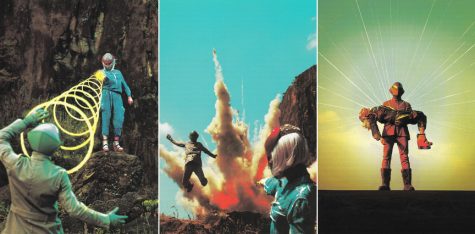

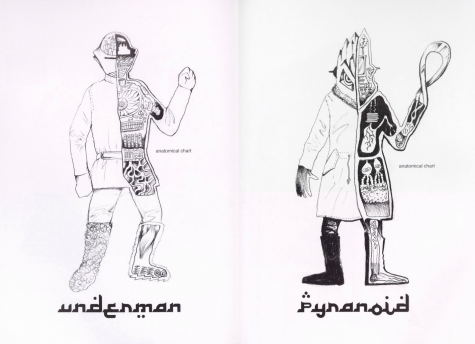

“UNDERMAN” does something that Fisher describes is present in a lot of today’s new media and that is its recycling of the past’s vision of the future. It embraces a retro-futuristic aesthetic and takes inspiration from Japanese television shows like Ultraman as well as Kamen Rider in order to weave a narrative about Takahashi’s own original character Underman. The lookbook conveys a story concerning the titular character attempting to save the world from soul stealing monsters.

In “UNDERMAN” we find a vision of a future from the past. The people in the past envisioned our future to look something like this, high-tech almost alien equipment and clothing composed of synthetic materials with minimalist designs made for functionality. What is strange about this futuristic aesthetic is that the times for which people have envisioned such a future have passed. By 2020, it was probably assumed by those in our past that we would have flying cars, yet today resembles nothing of what the people in our past thought it would. Yet this vision for the future still persists in our media today.

In the lookbook for this collection, there is an associated text that is meant to go along with the picture and explain what is happening. One of them reads “The year is 20XX. The world in which the souls of the people have been incapacitated by the forces of evil, is empty.” The text demonstrates the persevering notion of our only vision of the future coming from decades before where 20XX is the near but unknown future.

The modern era is a confusing time because even though we have gotten to the fabled era that the past believed would be different, we continue to subscribe to their notion of the future. You would think that since we made it here and we have seen how differently it played out, we would be able to envision a more clear and realistic future, and yet we still allow the past to have such a large influence on our conception of it. In this way we uphold the cancellation of the future, because we allow such ideas of the future to be our prevailing understanding of it.

Regardless, Takahashi’s work on this particular collection is fantastic, the pictures taken for the lookbook are expertly photographed and edited, and they contribute incredibly to the flow of the narrative. The inspiration for the characters can be seen quite plainly, but Takahashi takes this inspiration and turns it into something completely of his own. One of the stories about how a particular photo was taken is quite interesting. There is a video wherein Takahashi and his team are seen in the rocky locations where the whole collection was photographed, and they set off a carefully controlled explosion which creates one of the most iconic images of the collection. You can view the entire lookbook here.

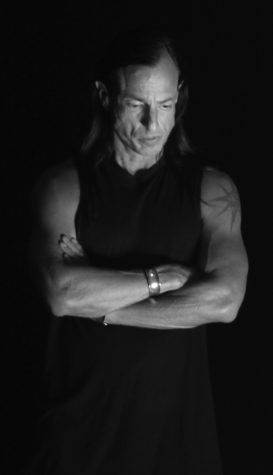

Rick Owens and Subversion

In terms of current architects of the new, Rick Owens stands out among the contemporary designers. He is like a modern Leonardo Da Vinci; he works in fashion, furniture, and sculpture, like a true Renaissance man. What is so groundbreaking about Owens’ work are the cuts and fits of his clothing designs. To the untrained eye, they seem odd and dysfunctional. While much of his work does stray away from the standard fits and designs with which people are comfortable, his choice to do so defines his work. In Rick Owens’ oeuvre, we are much less focused on print and instead we are interested to see what he can do with materials, where he can implement them, how he will cut them, and what he sees as the ideal way on which they rest on the human form.

All of his models are carefully picked to suit his vision of the garment, and the garments themselves are designed to augment the body in every way possible. This process brings out some of the most unusual and beautiful garments of this century. Accentuated shoulder fits that look awkward on regular clothing become integral parts of the garments in the context of Rick Owens.

Even though his designs are avant-garde, Rick Owens has made a profound impact on popular culture and has skyrocketed in popularity because of it. Unlike Raf’s work, Rick Owens has less of a susceptibility to become corrupted. With Owens, you cannot just put on a popular piece and gain social recognition. Instead, to put together something with Owens, you have to have a genuine understanding of his work or you will end up looking foolish.

Owen’s entrance into popular culture may do a lot to inspire others to conceive of new culture. Rick Owens cannot be easily accepted by the mainstream because of how far he goes from it. As his work becomes exposed to more people, they may be able to understand it and delve into the same abstract that he does. This will completely shift the fashion standard towards the new.

Rick Owens is a part of the new future that drives past the one that is cancelled by the hauntological mainstream culture. Whether or not this new future comes to fruition or not is dependent on whether enough new culture can be generated, a culture that is divorced entirely from neoliberal influences and pushes it to its breaking point. The future of tomorrow is either a cancelled apocalypse or an abstract new.

We are intoxicated with the past cultural forms, to the point that we are only interested in consumption in the present and are not worried about the consequences that such a consumption may have on our future.

Rahib Taher is a Copy Chief for 'The Science Survey.' He enjoys journalistic writing as it gives him the liberty to write about topics that interest him....