Smells Like Zine Spirit

Zines are not just small magazines; they’re a culture for teens, misfits and ostracized communities.

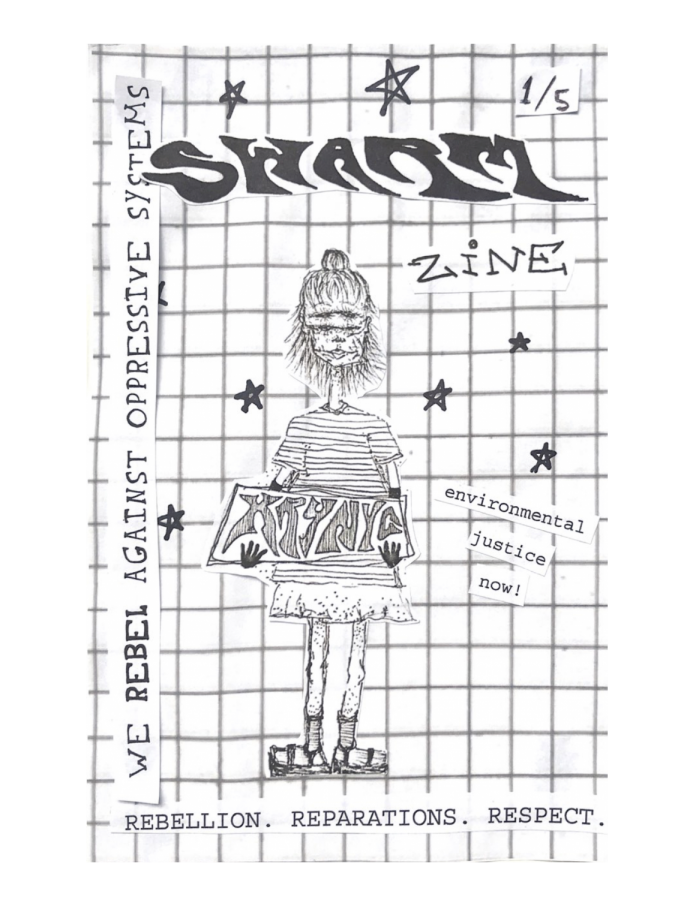

XRYNYC’s Swarm Zine was distributed all over New York City. It was used as a tool to educate communities on environmental racism.

Tucked into crevices of park benches, taped to a lamp-post with a radical sticker, or stuck in between the pages of a book at the Strand Bookstore, you might find a small, collage-style, black and white mini-magazine—Swarm Zine. In true guerrilla fashion, the small publication is DIY, black and white, and distributed so that everyone — especially those who would be less likely to seek it out — may see it. Swarm is a new initiative by Extinction Rebellion Youth NYC (XRYNYC) to educate the city about environmental racism, knowing that art is vital to engage the masses.

XRYNYC has long understood that art, and zines, are an important tool of change. “Through XR’s exploration of tactics and through our discourse and discussions on movement theory, we’ve found that art is an extremely powerful tool of radical change in that it goes against the capitalist grain of hyper-productivity,” said Sophie Anderson, XRYNYC’s coordinator. “Art is about slowing the pace and critically analyzing issues and emotions through a slowed pace. It is also, obviously, quite eye-catching. It draws more people into the movement, inviting them to learn more about something they might initially feel intimidated by.”

XRYNYC is among thousands of other collectives and individuals expressing their art, anger, perspectives, emotions, and anything else through the do-it-yourself style publication tagged “zines” — which, like the name, are smaller, more DIY versions of magazines. The members of the climate justice collective immediately flocked to zines as a way to invite the city into the discourse on environmental racism and the systemically oppressive root causes of the climate crisis. They added themselves to a long and robust history of zine-making, gleaning from, and adding into the zine culture and community.

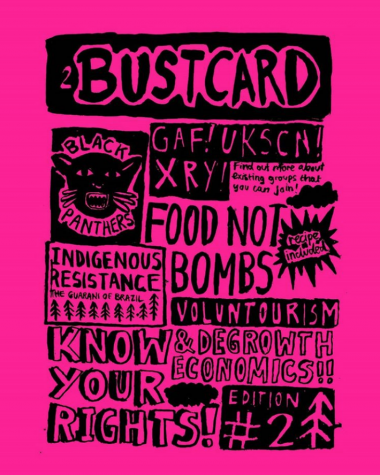

This history of zines is nonlinear, but it paints a picture of what the subculture means to different generations. Zines are not just confined to a single definition; different individuals and collectives define their meaning of zine for themselves. While this definition is makeshift, the most important aspect that constitutes a zine is that the publication identifies as one. Part of the culture of zines is that they are multitudinous and vast in their content and intention. Simply put, though, “zines have the potential to interrupt the bubble. In a time when our worlds are curated to affirm our existing individual or societal beliefs, this physical item disrupts and challenges existing dominant narratives,” said the team at Bustcard zine, an ecological and anti-authoritarian zine based in the UK.

Even the process of creating a zine can be considered radical. Often, zines conform to (most of) these standards: small circulation, self-published, low-cost, and DIY. At Bustcard zine, their decentralized process defines who they are. “No one has more power than anyone else,” said Freya, one of the team members. “What is very central to Bustcard’s identity is that we don’t censor people’s ideas. We are uncompromisingly anarchist and radical in the way we write our articles. We don’t want to be more liberal or watered down to try to appeal to certain people, though we still want to be accessible to these people. that’s why we have the glossary, to break things down and make sure we’re using accessible language to people who aren’t necessarily in the movement — but we still want to be as honest as possible about our ideas.”

Zines create their own space when the media is largely usurped by mainstream voices and topics. They make room to talk about those things we rarely see on screens, in editorial magazines, or in books. Mainstream media often distorts or ignores systemic issues — like environmental racism. “One main difference between mainstream publications and zines is money. The fact that capitalism has such a stronghold over magazines, and magazines can’t really exist without advertising show that they are a capitalist product created to be sold.” Zines reject that toxicity and embrace a more pure, unadulterated form of communication. Generally, zines are most popular among ostracized communities, those that are either marginalized from the mainstream or those that reject it. Typically, zine movements are forefronted by youth, communities of color, radical activists, feminists, and oddball artists: those whom the people that conventional media often ignores.

The history of zines is deeply rooted in using the medium as a way to advocate for change and give voice to the silenced. Self-published pamphlets had their places in radical historical movements during moments of monumental change in the United States. In fact, “guerrilla” style homemade pamphlets helped to advance the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. The Black Panther party also handed out small publications to disseminate their ideologies. Zines have also been central to the queer community for quite a long time as a method of expressing parts of the culture that were frowned upon (or criminalized) in the latter half of the 20th century. The riot grrrl feminist movement of the 90s relied on zines to spread their message and create an alternative space in contrast to the male-dominated punk scene of the past.

It is no surprise that these communities might be attracted to zines to express their messages or art. They provide a perfect, uncensored, no authority alternative to mass media to distribute their ideas. “What is most ‘radical’ about the zine process,” Anderson said, “is that it’s typically self-published. The utility of zines is that they allow minorities and youth to create their own spaces that are not restricted or censored by mainstream standards. Zines reject the notion that we have to be reliant on exclusive, often oppressive mainstream industries in order to disseminate our ideas and anger. Zines are anti-establishment.”

Clearly, these demands are timeless. While zines have always been popular among radical youth, they are especially hot right now. No coincidence there — as many youth communities are experiencing a rapid radicalization amidst perpetuated social injustices, and as the mainstream media seems at its pinnacle of lacking plurality and representation, youth and minority communities are looking for ways to express their anger, love, joy, grief in a method through which they know they will be heard. “Zines create your own mode of transportation for your message rather than relying on others to spread your message for you,” said Helen Stone ’23, one of the co-creators of Bronx Science’s new intersectional feminist zine.

So, if you happen to come across one of XRYNYC’s Swarm Zines, or otherwise encounter a physical zine, know that you are engaging a rich lineage of artists and changemakers trading ideas, history, and anger. “Zines, being a physical object, can interrupt your reality,” said Freya. “Zines subvert the algorithms of social media that determine what we see and that appeal to our opinions. Zines break down those barriers. They open you up to someone else’s world.”

“Zines reject the notion that we have to be reliant on exclusive, often oppressive mainstream industries in order to disseminate our ideas and anger. Zines are anti-establishment,” said Sophie Anderson, coordinator of Extinction Rebellion Youth NYC.

Edie Fine (she/they), an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey,’ is thrilled to be on the journalism staff for a second year. She loves telling stories,...