Can Lebanon’s Use of Media Save Its Revolution?

Despite Lebanon’s sixteen major religious sects, the Lebanese people stand united in the current revolution.

From viral Instagram movements to popular Netflix originals, media has quickly become an important part of international activism. In countries with high censorship and propaganda, creative use of media has become a common route for self-expression and political dissent among the people.

In Iran in the late 1960s, the activist movement known as the “Iranian New Wave” took to film in order to criticize the government. Faced with many restrictions and bans, “directors began to create films under the pretense of documentaries or entertainment films so that they could be viewed legally,” said Zhi Zheng ’21, the secretary of Film Production Club. When Iranian film director Jafar Panahi was banned from making movies, he posed as a taxi driver and produced “Taxi,” a docufiction film that reveals the social challenges of living in Iran. “This idea of combining films with reality is called pseudo-realism; activist movies like ‘Taxi’ are products of film and reality, where the director isn’t directing the vision or film, but rather becoming the vision and becoming the film,” said Zheng.

More recently in the Middle East, Lebanon has seen a shift towards film and media to correct misconceptions of Lebanon abroad. In 2017, “The Insult” was nominated for an Academy Award for its reflection on the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War twenty-eight years later. The film was praised for exposing the status quo in Lebanon to an international audience. More recently in 2019, Nadine Labaki’s “Capernaum” was also nominated for an Academy Award for shedding light on the slums of Beirut, an issue that has been largely invisible to the country’s middle and upper class.

Despite this, misrepresentation in the news has been a common theme in Lebanon’s history, especially regarding the current Lebanese revolution. “News reports and media have a big effect on the revolution because they portray it so differently from the truth. For example, the news made it look like the revolution was started because of a WhatsApp tax, but it was so much more than that. They don’t show all of the corruption in Lebanon,” said Megan Kazan, a student at Broumana High School in Lebanon. While news reports may not always cover the full story, Kazan believes that “Instagram movements and the Lebanese film industry raise a lot of awareness, especially since social media is accessible to everyone. Unlike the news, with social media those in power can’t choose what gets covered.” Amal Masri, another student in Lebanon, agrees with Kazan’s claims. “International news outlets are trying to discourage the people by spreading a wrong image about what is currently happening. After thirty years, Lebanese citizens are finally demanding the rights they’ve always deserved,” said Masri.

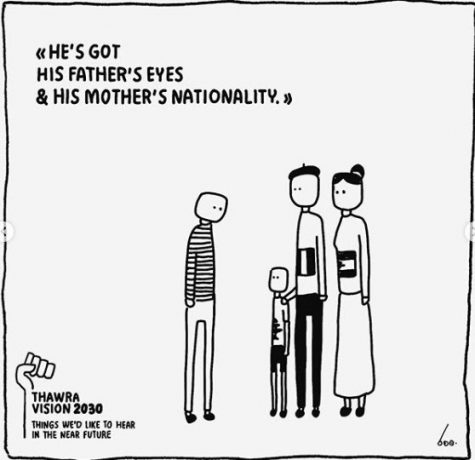

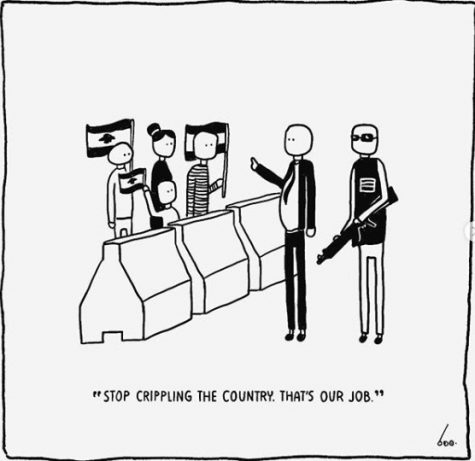

Today, activism in Lebanon takes the form of social media, film, art, and more. The Instagram account @the.art.of.boo is a prime example. The account posts satirical cartoons that shed light on the absurdities of Lebanese politics and society. One of their most popular cartoons portrays a family with a French father and Lebanese mother with subtext over their son stating, “he’s got his father’s eyes & his mother’s nationality.” The catch is that Lebanese women can not pass their Lebanese nationality to their children — that right is reserved exclusively for men. The account posted the cartoon as a goal for 2030 with many other cartoons that reveal the lack of basic rights and resources in Lebanon right now. The revolutionist art movement is also captured by the instagram account @art_of_thawra, which uses the Lebanese term thawra, or revolution, to categorize works by various artists that convey the protests.

Lebanon’s use of social media in its current revolution is nothing new to the international community. The 2016 Paris terrorist attacks sparked the “Pray for Paris” and “Je Suis Charlie” movements in which people from around the world used their social media accounts to resonate with the victims of the attacks, including the cartoon company Charlie Hebdo. More recently, the #BlueforSudan movement went viral in the Summer of 2019, creating a wave of blue profile pictures across Instagram and Facebook in solidarity with the Sudanese revolution.

While social media seems to have become our go-to method of expression and awareness, for people in nations facing censorship and global misinformation, it is a last resort plan to be heard. “Past events have proved that media will always be important for activism, whether it’s the anti-war music from the Vietnam era, sci-fi stories such as Fahrenheit 451 which serve to critique society, or a movie or T.V. show simply including a more diverse cast,” said Davide Hallac ’20, the president of Film Production Club. “Film and media will continue to be important for activism in the future, as long as people still have messages they need to deliver and causes they need to fight for.”

Today, activism in Lebanon takes the form of social media, film, art, and more.

The Lebanese people unite under one flag as they take to the streets to protest corruption in the government.

Lebanese flags wash the sky in red and white as protestors flood the streets of downtown Beirut.

A Lebanese woman passes her nationality down to her son, an impossibility given current Lebanese laws.

Politicians blame protestors for crippling Lebanon’s economy in a satire meant to expose the economic corruption that exists in the Lebanese government.

Celeste Abourjeili is the Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.’ She has a passion for journalistic writing because it gives voice to all groups...