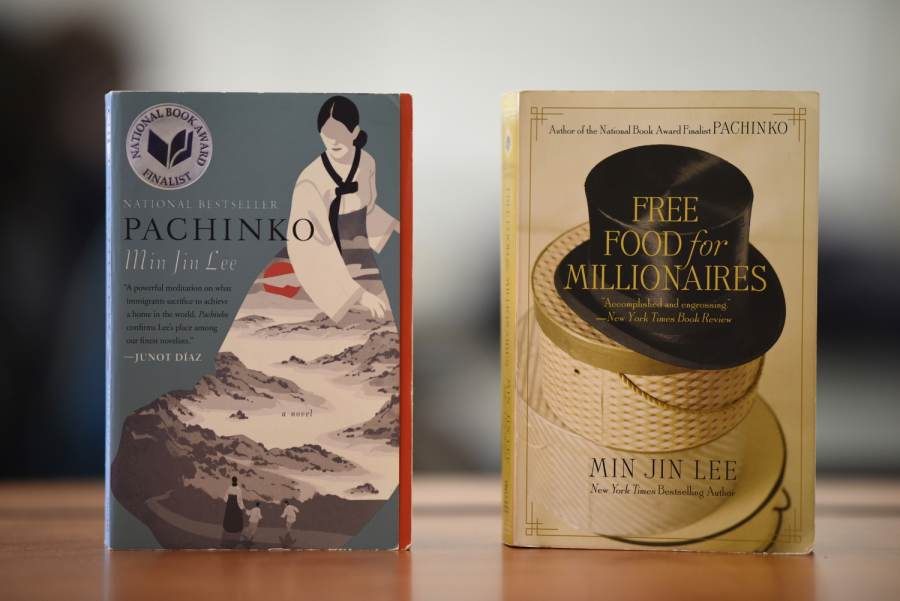

‘Free Food For Millionaires’ and ‘Pachinko’

Min Jin Lee’s Powerful Novels on the Korean Diaspora

Min Jin Lee’s best-selling novels, ‘Pachinko’ and ‘Free Food for Millionaires.’

In literature, we seek to understand ourselves and learn something new. And that is exactly what Min Jin Lee’s novels, Free Food for Millionaires and Pachinko, allow readers to do. Lee, a Yale and Georgetown graduate, author, former lawyer, and our Keynote Speaker at this year’s graduation ceremony, has written about culture, politics, and travel for various publications including ‘The New Yorker’ and ‘The Guardian.’ Her two novels, both national bestsellers, have garnered places on over seventy-five “best books of the year” lists. Her most recent novel Pachinko, published in 2017, was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. Both of Lee’s novels make up the first two parts of a trilogy she is writing about Korean diaspora.

Free Food for Millionaires, Lee’s debut novel published in 2007, tells the story of the indelible Casey Han, the Ivy-League graduate daughter of Korean immigrants, as she navigates life after college. A first-generation student thrown into a privileged world full of riches that she eventually grows far too accustomed to, Casey is forced to deal with her desire for a lifestyle that she cannot afford after she graduates from Princeton University without a job. Free Food for Millionaires follows Casey as she struggles with her personal, romantic, and professional endeavors in her post-graduate life.

“It could be a lens through which to understand what it means to grow up in a community characterized by sacrifice and cultural anxiety and a powerful way to explore the significance of class and immigration.”

The beauty of this book resides in the way that Lee captures how love manifests and expresses itself, particularly within the Asian-American immigrant community. With a strong ensemble of characters, Lee weaves an intricate picture of the relationships that hold a community together and the ideas and beliefs that can drive it apart. Lee also presents different types of love, giving readers a more holistic understanding of the community.

As many East Asian immigrants and children of immigrants can tell you, love, particularly between parents and their children, is often not expressed through physical affection or explicit verbal sentiments, but rather through acts of service. Free Food for Millionaires illustrates this dynamic beautifully. Love blooms in the care that Leah, Casey’s mother, puts into preparing dinner for her husband and children every night, the long hours both parents work at a dry cleaning store to finance their children’s education, and the high expectations for success. Without an intimate understanding of East Asian culture, it may be difficult to understand the love that exists between Casey’s parents or between Casey and her parents. However, Lee captures the nuances of each interaction so carefully and gracefully that even readers who aren’t East Asian immigrants can come to understand the nature of and expectations in Asian-American relationships. The result is a stunning story that crosses cultural boundaries.

*Beware: minor spoiler in the next paragraph.*

In Casey, I see myself: a young woman struggling to reconcile her ethnic roots with her American upbringing and balance the expectations of her parents and other adults around her with her own desires. In her counter-intuitive actions, from refusing help from her wealthy friend and mentor Sabine, to get into a top business school, to cheating on her boyfriend with her flirty coworker whom she doesn’t even like, I gained a better understanding of my own desires and actions—or more accurately, I better understood how I didn’t want to act, because quite frankly, Casey’s actions annoyed me. But it is in the way her story is set against the backdrop of her community that I could see the effects of that community on her, and consequently understand how my own community shapes me as a person. Reading Casey’s story was like having a therapist from Barnes & Noble that only cost $14.99 to sort through my problems.

For me, Free Food for Millionaires was the mirror in which I saw my own life as the daughter of Chinese immigrants. For others, it could be a lens through which to understand what it means to grow up in a community characterized by sacrifice and cultural anxiety and a powerful way to explore the significance of class and immigration.

Min Jin Lee’s second novel, Pachinko—named after the Japanese pinball-like slot machine game—is a remarkable historical exploration of the effects of war, poverty, and the accumulation of wealth on the survival of the Korean-Japanese, an immigrant community that has been treated with contempt for decades. The story focuses on one such family over four generations. It begins with Hoonie, the only surviving son of an aging fisherman and his wife. Hoonie eventually marries the daughter of a poor farmer whose land was taken from him after Japan annexed Korea. The pair have a daughter, Sunja, who becomes pregnant at sixteen from a rich mobster from the Korean mainland, Koh Hansu. Refusing to become his mistress, she marries a young tubercular minister passing through her small town of Yeongdo in Korea and moves to Japan with him where her first son Noa is born. Despite Sunja’s refusal for any help from Hansu, he remains a central character in her life for decades, paying for her son’s university education and sheltering Sunja’s family when Japan enters World War II. Soon Sunja has a second son, Mozasu, who grows up to be a wealthy pachinko parlor owner and have his own family.

“History has failed us, but no matter,” begins this poignant novel. Through the Japanese annexation of Korea, World War II, and the Korean War, we see how the trauma of these events changes the other characters as much as they change each other. We see how they overcome the obstacles in their lives in their fight for a better future. Lee argues that history has failed marginalized groups, such as the Korean-Japanese of her story, by stripping them of their humanity. This is a particularly important lesson to internalize and understand in the context of the socio-political atmosphere of America at the moment where we have a president who has taken a hard-line stance against immigration. Lee infuses each character with a humanity and depth of emotion that compels readers to root for them, to celebrate with them, and to cry for them, making Pachinko an empathetic commentary on the abilities of people to survive and maintain their identity in the face of forces that act to strip them of it.

Pachinko was an evocative read and a profound learning experience. When I first picked up the book from Barnes & Noble, I did not know what to expect. Yet three days later, I found myself in bed at 3 a.m. with tears in my eyes, mourning the characters I was now leaving behind after such a trying journey. Prior to reading Pachinko, I knew few details about the discrimination faced by ethnic Koreans in Japan because their voices and stories are not represented in media and literature. As an immigrant, I understood some of the trials that accompany being part of a marginalized group, but as a Chinese-American, I did not face the same issues or tribulations as the Korean-Japanese. Pachinko gave me extraordinary insight into this complex history and helped me become a more empathetic person.

In Lee’s novels, there is a community in the characters who accept you willingly into their stories. You become part of their lives and in that magical opportunity, you learn a great deal about what it means to be human.

Yanny Liang is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey’ and a Student Life Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ She finds journalistic writing incredibly...