“What is worth more, art or life?”

“Are you more concerned about the protection of a painting or the protection of our planet and people?” a protester from Just Stop Oil yelled at a mass of journalists and museum-goers as security officers pulled them away from Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers.’

Paintings and sculptures have a certain allure to them. Humans have always been drawn to the creation or replication of beauty, from cavemen’s etched narratives to picture-perfect portraits of kings and queens to more modern multimedia artwork. And, for as long as art has existed, it’s been political.

As Palestinian poet Marwan Makhoul wrote, “In order for me to write poetry that isn’t political / I must listen to the birds / and in order to hear the birds / the warplanes must be silent.”

Of course, not every work of art is political at first glance, and here we see the dilemma facing Just Stop Oil protesters and environmentalists worldwide. Is it justifiable to turn seemingly apolitical artwork into a bargaining chip for a larger movement?

Like many others, I first learned about Just Stop Oil on TikTok. Videos of young protesters splashing tomato soup across Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ went viral in October and November of 2023. The comments sections were brutal – some commenters called them hypocritical for throwing soup while railing against food waste, and many asked, “What did Van Gogh ever do to you?”

I was intrigued. I started looking into the organization, and protest-art-vandalism as a whole. Unsurprisingly, the issue wasn’t as black and white as social media made it seem.

Just Stop Oil is the British section of the A22 network, a coalition of environmental organizations around the world protesting climate change through direct action. The network has branches in eleven countries so far, each with different goals and methods.

The videos I saw on TikTok showcased one type of protest by Just Stop Oil – what they call their “art actions.” In most of these actions, activists glue their hands to a painting or its frame, and sometimes they throw soup, paint, or ink at the painting. The paintings they choose have two things in common – they’re all famous, and they’re all behind glass.

So far, JSO protestors have never caused direct damage to a painting. They’ve thrown soup at the painting’s protective glass, broken that glass, or glued their hands to the painting’s frame, but they haven’t destroyed anything.

And, even though the vast majority of their news coverage centers around their art actions, the organization’s work does not stop there. Just this year, they have blocked highways, disrupted Labour party fundraisers, interrupted major sports games, and protested against specific MPs (members of the British parliament). Just Stop Oil’s goal is straightforward – stop all new oil production by any means necessary.

On November 6th, 2023, two Just Stop Oil protestors smashed the glass casing on Diego Velázquez’s iconic ‘The Rokeby Venus’ at the National Gallery in London, England. I was particularly interested in this action – not just because it represented an escalation from throwing soup, but because on March 10th, 1914, a British Suffragist named Mary Richardson took a knife to that same painting.

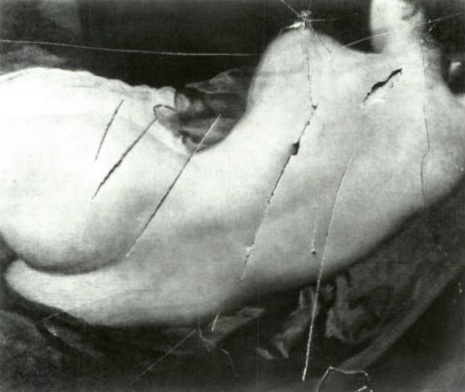

‘The Rokeby Venus’ is a nude portrait of the Roman goddess of love and beauty, painted in the mid-sixteenth century. Even back in 1914, the painting was displayed behind glass in London’s National Gallery. Richardson stepped up to the painting, pulled a meat chopper from her sleeve, smashed the glass, and quickly made what she called her “lovely slashes.” The very next day, she was sentenced to six months in prison for “malicious damage.”

The day prior on March 9th, 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union, had been arrested. The WSPU focused on direct action and are described as one of the more militant suffrage groups. They were often arrested, and Pankhurst saw that as a means to publicize the movement, but the violence of her arrest sparked outrage.

Richardson explained her attack on the painting while in custody. “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history,” she said, “as a protest against the Government destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history.”

The painting was soon restored after the 1914 incident and has been back on display in London’s National Gallery until the recent Just Stop Oil action.

Much like the modern climate action movement, the British suffragist movement took part in its fair share of vandalism. The previous year, two suffragists had taken hammers to the glass casing of thirteen renowned artworks at the Manchester Art Gallery. Richardson’s action alone inspired 14 more painting slashings around England, including Giovanni Bellini’s ‘The Agony in the Garden’ and John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Henry James.

Watching a video of JSO’s Rokeby action online, I was struck by how calm it seemed. The protestors, Hanan Ameur and Harrison Donnelly stepped over the rope sectioning off the painting. They took out small, orange hammers and began smashing the glass covering ‘The Rokeby Venus.’ After getting in a few hits, they turned around and spoke.

“Women did not get the vote by voting,” Ameur shouted. “It is time for deeds and not words. It is time to Just Stop Oil!”

The two protestors then stepped back over the rope, knelt on the ground, and grasped hands. They were arrested and kept in holding overnight but were released on bail the next day. Ameur and Donnelly are currently awaiting trial for criminal damage over 5,000 pounds, which has a maximum sentence of 10 years.

I reached out to A22 a few weeks ago and set up a Zoom meeting with Hanan Ameur and Harrison Donnelly. I had a lot of questions.

ACADIA BOST: How did you first get involved with climate activism?

HARRISON DONNELLY: As a kid, growing up, we’re taught about climate change in school, but nobody’s doing anything. It’s an apocalyptic level event, and I just needed to do something, because, you know, ‘if not me, then who, and if not now then when.’

AB: How did you decide to work with Just Stop Oil as opposed to another organization?

HANAN AMEUR: Other organizations were a little too… ditsy, I think is the word. They were like, “Think of the polar bears!” I mean, we’re going to see billions of people displaced from their homes. It’s bigger than that. [Just Stop Oil] was focused on giving power back to the people. It’s like a revolution. It was obvious that’s what needed to be done, and Just Stop Oil was the only organization doing that.

AB: What are your personal goals, and what are Just Stop Oil’s goals?

HA: From my perspective, I just want a hint of change. I mean, people always say we’ve cut emissions, but we haven’t, we’ve snuck around reporting our emissions, and there are loopholes. We’re not irrational, we’ll compromise, but I want the government to see that we’re in an emergency and make some changes.

HA: What does Just Stop Oil want? It’s in the name! No new gas and oil from the North Sea and phasing out the [oil rigs] that do exist. We’d like to stop by 2030; that’s the goal.

AB: Do you feel like you’ve seen any of the progress you’re looking for in the time you’ve been working with Just Stop Oil?

HA: I think that many more people are paying attention. I’ll give you an example — I have a friend whose mom lives in India, and she’d heard about my action before [my friend] had even met me. She’s seen the climate, and she was like, ‘This is great.’ The Rokeby action went viral in the Dominican Republic, and I had a lot of Dominican friends who loved it. They’re seeing the flooding, they’re seeing the climate get worse, and they were like, “Yes, we need this.”

AB: What’s the main goal right now, is it awareness, fundraising, political candidates?

HA: The goal right now is to see real political change. We’ve got an election year coming up… The key thing is independence; we’re not with Tory or Labour. We’ve got citizen assemblies — in Ireland that’s how they legalized abortion, that’s how they legalized gay marriage, so it’s about giving political power back to ordinary people.

HB: I’m a normal guy. I’m not here to get involved in Labour, or Conservative, or politics, I’m your average guy. And I think everybody, from your top Tory politician to the people living on the streets, knows that the climate is getting bad.

AB: Pivoting slightly, do either of you have a very personal connection to art?

HA: I have a level three in performance art, I love musical theater, and I sing. I’m surrounded by creatives; I’m only in creative spaces – art is very dear to me.

HD: I’m a philosophy student, and philosophy is art to me – everything is art to me. I love drawing, I loved drawing growing up. We didn’t destroy the art — we destroyed a pane of glass, and I feel like that’s the part people are missing out on.

AB: What were the consequences of smashing the glass?

HA: The charge is criminal damage over 5,000 [British pounds], initially it was [criminal damage] under 5,000, but they bumped it up. It was just the pane of glass — that’s the only thing that was damaged — so when we first got arrested, they said it would take about 600 pounds to fix it, but a few months later, they racked the bill up to 6 grand. The prosecutor said there was little to no damage to the painting itself, so my lawyer’s trying to figure out how exactly the bill got that high.

AB: Do you think jail time is something that would be productive to your cause, is that part of it?

HA: I mean we pleaded Not Guilty. We’ve got people doing [time in prison], who I admire greatly. Its amazing work, but I don’t feel we’re getting jailed for this.

HD: I’ve had to waste a night in a holding cell. I’ve had to waste my childhood learning about the climate crisis… my future’s been sold to Shell and BP, so if I go to jail for 6 months or 3 months, so be it. The government’s stolen everything from me; they can steal another 6 months.

AB: Was there a lot of discussion about Mary Richardson when you were planning the Rokeby action?

HA: We focused more on the Suffragette movement than on Mary herself. We were thinking, this is what the Suffragettes were doing. This is civil resistance. This is how change happens. I always think of the freedom fighters, when they went down on the bus every day and got beaten up, and the next day the bus would come.

HD: The suffragettes are proof that these methods work, and that’s why we emulate these methods. The suffragettes slashed that very painting, and they changed the world massively. If only we could do the same.

Mary Richardson didn’t win British women the right to vote by slashing a painting, but actions like hers undeniably helped. Her dedication to her cause, and her willingness to spend time in jail for it, meant something. It sent a message that women were powerful and that women were mad.

A movement using just one tactic to affect change cannot get too far. Time will tell the real-world impacts of Just Stop Oil’s targeted protest vandalism, but maybe this, together with marches, lobby groups, climate researchers, and policymakers, could make a change.

And maybe it won’t. But we’re too close to disaster not to try.

A movement using just one tactic to affect change cannot get too far. Time will tell the real-world impacts of Just Stop Oil’s targeted protest vandalism, but maybe this, together with marches, lobby groups, climate researchers, and policymakers, could make a change.