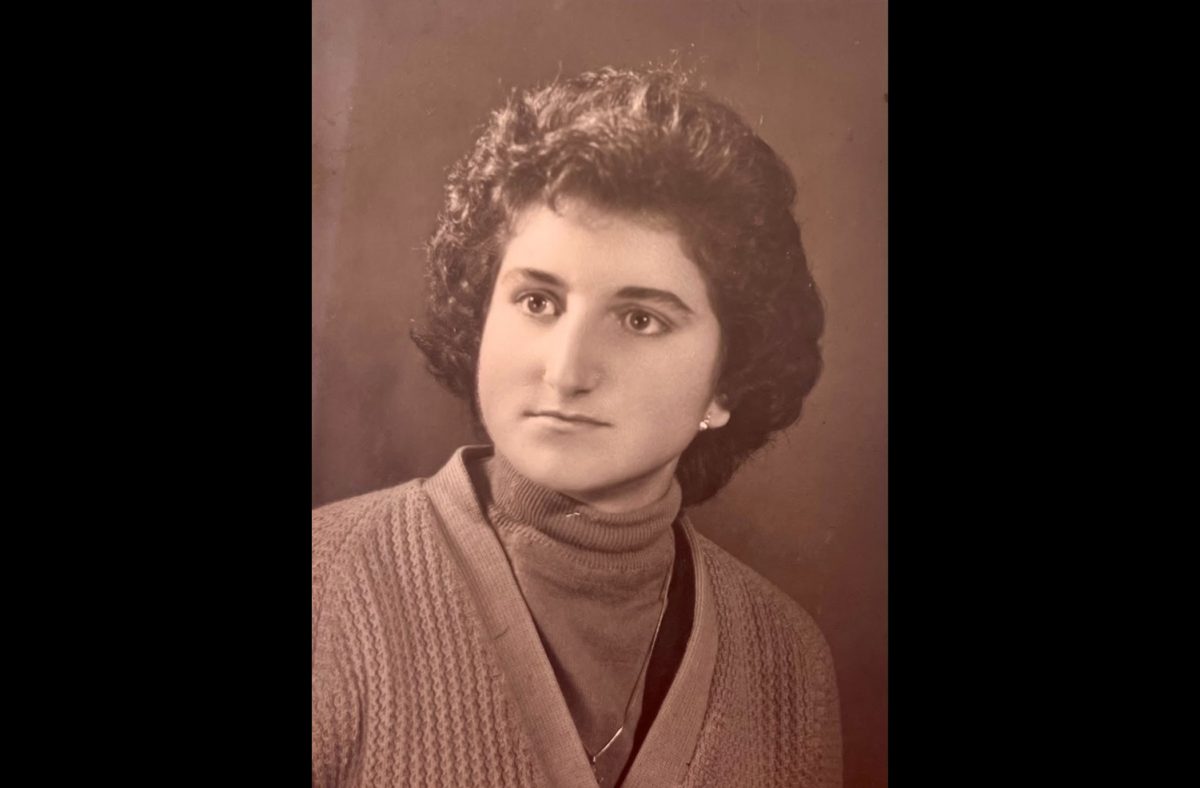

It was 1937, when Dina was born. Home was a mountainous region known as La Provincia di Frosinone, and life was the plants grown and the livestock’s supply. It was not long before the clear skies were clouded with bombs, and the land was scouted by soldiers who wanted to remove the citizens from the area. Hiding from these dangers, Dina and her family scrambled to get basic life necessities. This woman is my grandmother, whose story I was lucky enough to hear firsthand.

Early Years and War

A cool autumn wind whistled through the orange-red trees, hugging the steep mountains and the farmland. In Italy, tucked in a valley, was a beautiful farm, full of healthy vegetables, grazing animals, and a quaint stone house. Days were filled with laughter and labored breaths, as living on a farm was hard, winters were cold, yet work was rewarding and Dina’s family was comfortable.

In a distant place were whispers of war, but life went on. Suddenly, on January 17th, 1944, that whisper became a desperate cry. Dina lived only miles away from Monte Cassino, in La Provincia di Frosinone. As the Allied Powers and Nazi Germany arrived, the sky buzzed with overhead aircraft carriers, the soil rumbled as troops marched forth, and even the deepest parts of the land were demolished by explosives.

To the south, the hum of combat grew. Dina, at five years old, along with her family, abandoned their house and went further up the mountain to where there were scattered caves.

“I used to say, ‘Mama, why are they throwing bottles at Monte Cassino?’ And she said, ‘They are not bottles, they are bombs,’” Dina told me.

“We were eleven people…in these deep caves, from five o’clock in the morning to seven-thirty at night,” Dina said. Her family put a tree and dirt above the cave so that it was camouflaged with the landscape. Yet their hidden presence was hard to maintain. “You couldn’t even cough because the soldiers knew that people were hidden in these caves.”

It was only in the dark hours of the night when they would run back to a nearby house, owned by relatives, to get any bit of food.

“We had to kill the cow, and we brought meat into the cave… we did not have any bread, nothing.”

If caught, “you would go to the concentration camp. If they heard your voice [during the day], they would put us in the truck, like cows, and bring us to the concentration camp, who knows where.”

One of these nights, Dina’s grandmother, Giulia, was hurrying to the house. Hungry, cold, and scared, Dina and the rest of her family knew there was never a guarantee that they would all survive the war. Yet when Giulia never returned that night, it was a stark reminder. Later, Dina found out that she had been sent to a concentration camp in Central Italy.

“She died there… that’s what they told me,” Dina explained.

Between the bombs and fear, Dina’s father would tell her, “Don’t worry, we will survive.”

Residual War

The Battle of Monte Cassino ended in the spring of 1944, as blossoms bloomed and promise wafted through the air. The war ended soon after. Perhaps life could heal itself back to how it had been.

But the wind didn’t only blow promise; it blew ashes. “Only half a roof was left… It was cold. At that time we had no electricity, nothing. We made a fire to keep warm with the wood we found, [but] the smoke was so bad, so bad, we had red eyes.”

“When I hear the pistol noise or anything about war in the dark, I am traumatized. After the war, we were not allowed to have lights. If they see the light they would come and shoot you.”

When all felt peaceful, there were unexploded bombs scattered through the land – and thus that constant fear lived on.

At eight-and-a-half, Dina was put into the first grade. Dina said, “I loved school. I wanted school so badly, because there was no work… I had to sweep, clean the stable of the cows…wash my sister’s diapers.”

Every day she wore her ragged floral dress, one jacket she shared with her family, and a pair of shoes that her father made out of bicycle tires. That winter it rained nonstop, and as Dina said, “my feet were always wet.” She caught tonsillitis, a painful inflammatory virus in the throat. “The doctor said if the tonsils would not come out, they were cancerous, and they would choke me… [so] the doctor cut my tonsils with no anesthesia.”

In the two years following the war “we got better, and better, and better.” She finally had a dry pair of shoes, and her family was able to make some money off the land again. She was able to go to a special school for three years, “up the steep, steep mountain.” Rather than having to worry about constant threats to her life during the war, Dina could sigh a breath of relief as her life mostly recovered to what it had been before the war. She could be a child again, playing make-pretend games in the open air. But winter hit hard and cold, and Dina got double pneumonia. Her body was shutting down after long hours in the cold, but sweat beaded her forehead, and even breathing was hard.

“Everybody thought I was dying. The doctor said, ‘leave the girl alone. If she wakes up, she will survive. If not, prepare yourself.’ I never saw my father cry. Until that night.”

Surrounded by sweat-soaked blankets and loneliness, Dina finally fell asleep, thinking, would the morning come?

As Dina reminisced happily, “I slept the whole night. When I woke up, I said, ‘Ho fame!’ or ‘I’m hungry!’”

Dina again set out to school, and stayed there until she was thirteen. She was teased by boys in her class, but there was more food on the table. Her mind became immersed in pluses, minuses, and letters.

At that time, Dina recalled, “My father had cultivated a lot of land, we sold the pigs, chicken, grain… the economy was flourishing.”

Seeking a more challenging schooling, she then moved in with a family closer to Cassino, who hosted her for seven years. Dina kept herself focused, “I was a good student.”

Dina recalled, “In the summer time … I saw the sun going down. I said, ‘one day, I want to see the other side of the world.’

When the sun was halfway down, I said, ‘I wish I was somewhere else.’

I said, ‘I don’t like this life. I want to explore’… [but] I didn’t want to come to the United States.

I did not want to come.”

Leaving Italy

What is the American dream?

Dina certainly did not know, nor did she want to. She dreamed of going to business school, but her grandfather living in America wanted her to live with him and his wife. Dina recalls that he had come to Italy, in which “he saw how efficient I was, very patient, very lovable.” Perhaps in America, Dina could reach her high potential. She could live the American dream.

In a newspaper was a classified ad – a photograph and a caption, reading that a young Sicilian man was looking for a wife who he could marry and settle down with. Her grandparents took the photo, seeing marriage as a way for Dina to get to America. Settle down, and she was one step closer to the American dream.

Dina recounted:

“They showed me the picture. I told my mother, ‘I don’t like him.’”

Two people put together.

For a month, I did not agree… thinking, ‘I wanna work, I wanna study, when I’m in my thirties I could get married.’

Then, at one point, I agreed.”

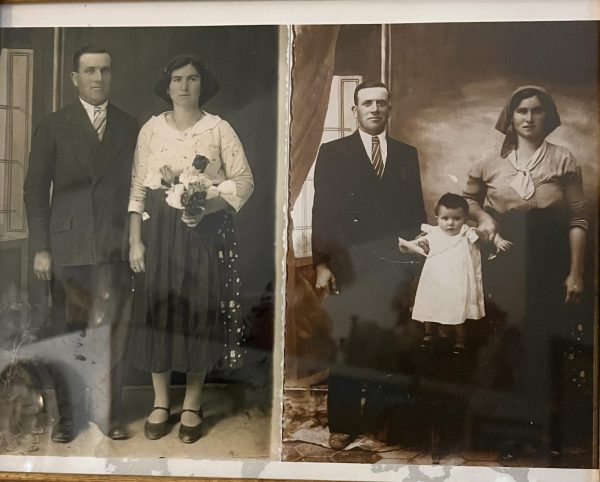

Mario visited Dina in June, to see if he liked her. They got married in July.

Dina confided, “I wanted to run away that day of the wedding… [but] I fell asleep and woke up at seven o’clock. The people were already coming to the house to wish good luck to the bride. So, I could not run away.”

Metal welded in a circular band, brought two foreign people together, for what they vowed would be forever.

The Italy Dina knew faded over the months she spent with Mario in his home in Sicily. Where Mario came from, “people live in huts, there was no bathroom… a hole behind the door… for everybody. [There was poverty] like when the war was on.” As tough as it was, she was able to start to learn Italian, and not dialect.

When Dina’s passport finally arrived, they left Sicily to the promising, glowing, and hopeful America. “They” was not just her and Mario… she was pregnant with a boy.

American Dream?

If you drive far enough into the industrial area of New Jersey, you will pass monotone rowhouses, filled with exhausted working-class people. Dina arrived at one of these houses, it was where her grandparents lived.

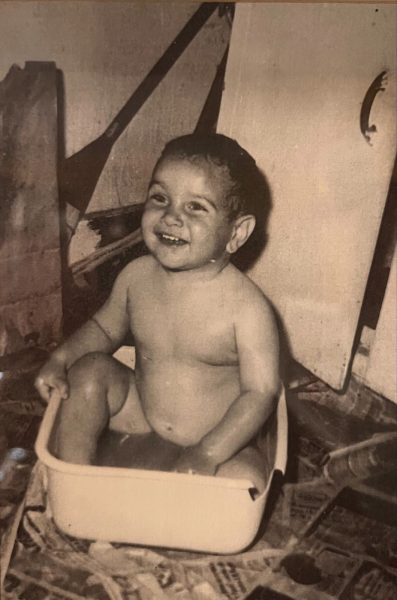

It was in the spring when her first son, Fiore, was born. “In the streets, people would stop me to tell me he was so beautiful,” Dina fondly recalled.

At home, her grandparents helped Dina care for Fiore. But, “There were fights every night [between my grandmother and Mario]. It was a nightmare. When Fiore was about three months old, we moved away.”

After moving to another part of New Jersey, jobs were too hard to come by, so they picked themselves up again to Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York.

In Coney Island, things were “a little bit better. Mario loved the baby… [but] we lived very poorly… we lived in the bungalow, and he was a dishwasher.”

Even though they lived together, Dina felt like she was in a bubble, as “he spoke Sicilian and I spoke my language… he was distant.”

One day, Mario told Dina, “You and Fiore go back to Italy.”

Dina told me, “You could name it an unwanted adventure.” But sure enough, when September rolled around, Dina found herself on a boat again. Instead of Mario by her side, it was Fiore. And instead of being pregnant with Fiore, it was with her second son Enzo.

The boat reeked of cramped bodies, and Dina kept Fiore by her side. Her legs ached. As the whole ground rose and fell to the rhythm of the water, it felt like a symbol of her life. Would there ever be still water?

“I cannot live here. I have nothing to eat. He does not send money,” Dina thought to herself as she gazed at her tough life in Palermo.

After several weeks, Dina heard someone calling her name. Her face was strong yet kind, and she welcomed Dina into her open arms. Her mother.

“Dina, we better go home,” her mother told her.

And so they did, and after her tumultuous year in America, Dina reunited with her roots. The land was healthy, money was sufficient, and she was no longer lost in a sea of unknown.

As the sweet smell of blossoms wafted through the crisp air, Mario visited Dina. Enzo, her second son was tottering around, five months into a new and hopeful life.

Dina was told by immigration people, “Your son, he is an Italian citizen. If he is going to complete two years in Italy, you’ve got to leave him behind.”

“I am the mother, I do not leave my children,” Dina had responded sternly. No matter what, she vowed to stick by their side.

Dina told me, “I had experienced a nice life in America with my grandfather. I wanted to better myself.” Perhaps the American Dream truly was possible – and she had seen a glimpse of it through her grandfather’s success.

“I had to make this decision,” Dina said.

Stay in Italy, or take a leap towards the American Dream?

Thread

Chiga-chiga-chiga-chiga

The needle broke the fabric, weaved the thin thread through, and pulled it out. A stitch! And it went on and on…

Dina loved it. She was living back with her grandparents now, making good money, and eating well. She met a kind woman, slim and well-dressed, who helped Dina learn more English. “Everybody was helping me,” Dina cherishingly recalled from her time in the sewing factory making coats.

Ever since she was back in America, she had not seen Mario.

“My husband found out [where I was]. [He said], I’ll change, I want to work, I want to support my family, the kids need a father,” Dina said.

“You [ever] not happy? Take a bus and come back [to New Jersey],” her grandparents had told her.

“But I was ashamed,” Dina told me.

“I love to help people… but I remembered a saying in my country– ‘Chi pensa per sé, pensa per tre.’ If you think for yourself first, then you help everyone else, you live much happier. It is nice to help people… but [unlike then] I learned to take care of myself first,” Dina now tells herself.

In the Woods

Alone and not speaking much English, Dina and Mario moved into the basement apartment of a 36-unit brick apartment building in the middle of Brooklyn, where they were the superintendents. Living in the super’s residence, they were able to get a cheaper rent. During the day, Mario went to work as an apartment painter, and the smell of turpentine filled the air at night when he washed the brushes in the shared bathroom sink. Fiore could go to school nearby, and Enzo was still too little. Everyone’s stomach was growling; the fridge had very little.

“But after two years, the owner said, ‘Mario, you got to move because you are not doing the job,’” Dina said. She herself had done some work, but the owner wanted them out. And so once again, they picked themselves up – now with two young boys.

“We had acquired a house in Upstate New York. We moved there in September, and I stayed there until March,” Dina recalled.

The house was a large, drafty, broken-down wooden colonial house, the type that could be beautiful if only there was time and money to fix it. They had gotten it all for a very low price.

Dina started to work in a dress factory. “[Mario] left and went to live in New York City because he said he could find a job. In the meantime, my father found a job washing dishes in a bakery at night. My mother did not like it up there…one day she left, and she went to Italy. So we were left there – my father, Enzo, and Fiore.”

Fiore walked a mile every morning to go to school and back home with his grandfather, where they walked a mile down the road at night to a sewing factory to sweep for a dollar a day. Even though they lived poorly, and their living conditions were unstable, education was incredibly important.

Dina recalled, “He used to come once a month. I got pregnant with Gia; I got sick for a month, I lost my job because the lady of the factory gave her cousin my machine.”

Dina stayed in the factory, now working part-time assisting a woman cut threads by the sewing machine. Dina tried her best, but this woman was reluctant to help.

“There is always jealousy when you work. But you work for you, not for them. My mom used to say, ‘you talk behind my back, that’s where you stay.’”

One bitter day she told Dina, “We do not have a job for you.”

The trees were bare, the wind felt like a slap in the face, and the house felt eerie as the windows shook and the cold could not leave anyone’s core. A blanket wrapped tightly around her body, she sat by the oven to try and warm herself. She was sick, pregnant, and lost her job. Next to her sat her two boys, their faces ashen and fingertips and toes as cold as ice.

Cold.

Dina told me that for moments like this, “First of all, You got to love who you are, really. Then, you got to love God. He keeps you going. My faith brought me places I never expected to be. A very good place.”

When Mario came to visit, Dina told him, “That’s it. The kids are getting sick because it’s cold over here; they don’t have proper shoes. Either you let me come to New York or I’ll tell the police you abandoned us, because you don’t give us money. Make up your mind, because I’m not going to stay over here.”

Beginnings and Endings

The waves grew, beautiful and thrilling, then surrendered to the whitecaps, crashing down onto the sand. The waves won again, pulling back and taking some sand with it into the ocean. The sound of children, car horns, and people shouting disrupted the tranquility. If you looked down the beach, there, boldly against the sun, stood Luna Park, a landmark of Coney Island. A few blocks away, lived Dina, Mario, Enzo, and Fiore.

“We lived in the back of the building…[it] was so cold. In the meantime my dad had to quit his job and come to New York. My father and the kids slept in the kitchen.”

After years of living in dangerous neighborhoods, cold winters, never-ending beans and boiled greens, and many, many jobs, the family had saved enough money. One day her father told Dina, “We can not live in this little room.”

Dina told me, “[my father] saved 2,000 dollars… at that time [that] was a lot of money. We found a house, and we lived there for fifteen years. The lady left the table, the chair, the china closet… the house was huge. Three stories, four apartments…We lived really nice and comfortably downstairs.”

School was out now, and the sun baked the squished gum on the streets. The tune of ice cream trucks mingled with the humid air and danced in the smell of salty water. Dina was blessed with a baby girl, Gia.

Between the good moments came the worse ones, where Dina feared, “If I have almost nothing to eat, how am I going to make milk?” The formula powder dissolving into the foggy water was perhaps another reminder of what she had lost growing up in the war.

Every day Dina put on her uniform for the Federal Reserve Bank. Maybe this job could stay, it brought in $78 a week.

“In the Federal Reserve Bank I had a tough time. The manager could see how well I worked. I minded my business, I kept the table very clean. I put everything together. This lady she said to me:

‘Huh you Italian, huh?’

I said, ‘Yea I’m Italian, I’m proud of being Italian.’

‘You should not work here!’

I said, ‘Why, what did I do?’

‘You belong to the Mafia, you should not work in the Federal Reserve Bank.’

I said, ‘Can you prove it? Go find out, go to the FBI and see where I belong. I belong here, at the Federal Reserve Bank. I work for my family and my pension.’

She left me alone.”

Little did she know, Dina would stay for the next 18 years. It was here that she was able to get her GED through long and tiring night classes, an ocean and decades away from when Dina had once envisioned.

Her parents returned to Italy to take care of their land.

Dina and Mario got divorced, and he passed away a few years later. As my dad tells me, “My father tried really hard to be a good man, and even though he didn’t quite become one, he tried, and that’s worth a lot. A couple years before he died, I went to visit him, he was still trying to learn, to grow, and he apologized.”

There was sadness, grief, confusion, and pain. Her family went home with what it now was, and what it is still today – Enzo, Gia, and Fiore. Yet now she has grandchildren, and a partner she has been with for almost 15 years.

I looked across the table at Dina. After our long conversation about her hardships and life she told me, “But anyhow, I am still here.”

The Florida humid air had a sweet-smell, and the evening light cast through the windows to the patio. In the house, I could hear my sister and cousin playing music in the background, my aunt and uncle and parents’ warm laughter, and smells of Italian food danced through the house.

I hugged Dina, and said what I will forever believe –

“Thank you Nonna, I love you.”

I looked across the table at Dina. After our long conversation about her hardships and life she told me, “But anyhow, I am still here.”