What is the first thing that comes into your mind when you hear the word ‘bird’? Is it a fierce eagle soaring through the sky? Do you think of the sea where albatrosses and seagulls thrive? What about the birds that survive in the coldest and driest of conditions? Or does the mind immediately picture a common bird that we often see?

Pigeons are in every major city, yet no one seems to particularly notice them. They are so common that various species and families of these birds that aren’t closely related are still considered pigeons.

Rock pigeons, carrier pigeons, passenger pigeons, and even doves are part of the Columbidae family. However, one of these pigeons doesn’t exactly fit in with the rest. Which of these is the odd one out? The answer: passenger pigeons.

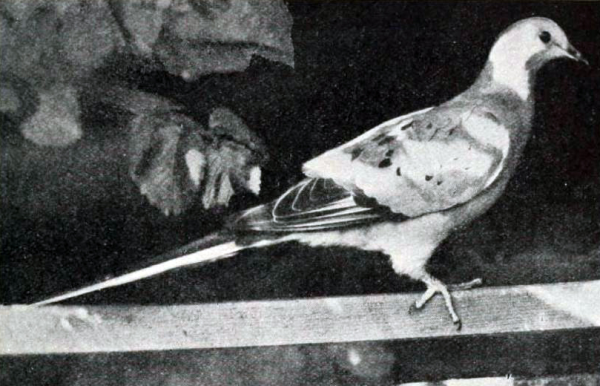

How are passenger pigeons different? Well, when you look outside, you won’t be able to find one. No matter how far or how carefully you search, you’ll never find one because passenger pigeons are extinct. They have been gone for over a century, with the last dying on September 1st, 1914, in the Cincinnati Zoo.

How is it possible for a member of the Columbidae family to go extinct? Aren’t these birds so common? Well in fact, yes, they were.

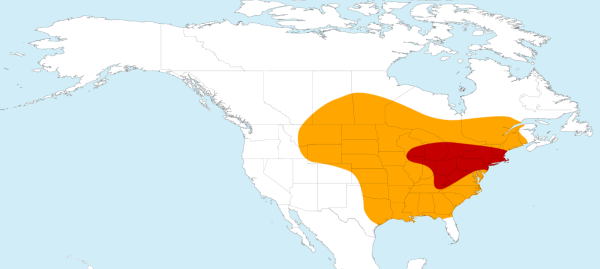

Passenger pigeons were once the most prominent birds found in North America, with an estimated population size of three to five billion. In comparison, one of the most common pigeons today, the rock pigeon, reaches an estimated 120 million birds worldwide; the passenger pigeon only inhabited North America.

Today, the conservation status of rock pigeons is listed as “least concerned”– implying they won’t be going anywhere anytime soon. However, considering that rock pigeons have a smaller population size, it is surprising that passenger pigeons, with a much larger population, were first to face extinction.

To understand this discrepancy, it is important to set the context in which passenger pigeon populations started to decline.

As the population of the United States continued to expand and traveled westward during the 1800’s, many pioneers of the time followed migratory routes of the passenger pigeon. Passenger pigeons were reported to travel in huge numbers – flocks ranged from a mile wide to 300 miles long, taking 14 hours to pass. The pigeons were abundant around the Great Lakes Region in the summer and traveled south (around Georgia and Florida) in the winter.

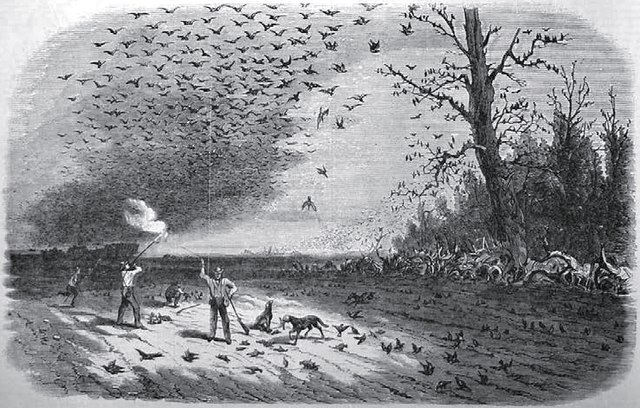

The travelers often related the huge flocks to thunder because the sounds of thousands of birds boomed in the sky. It was common for these early pioneers to see a storm of brown-spotted feathers, which darkened the sky. These flights often continued from morning until night and lasted for several days.

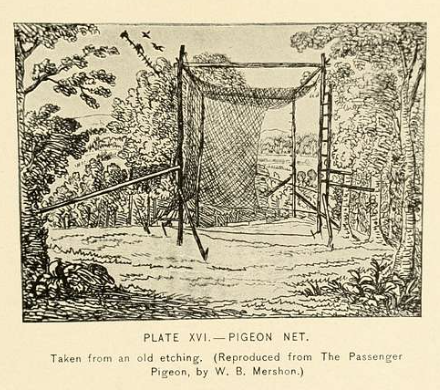

As the pioneers continued to travel westward in search of land, many had to live off of natural resources as they traveled, like food. Food was vital to the survival of families as they travelled. The easiest game? The passenger pigeons. Pioneers could easily aim their guns at the huge flocks of pigeons as they travelled by, and shoot the birds with ease.

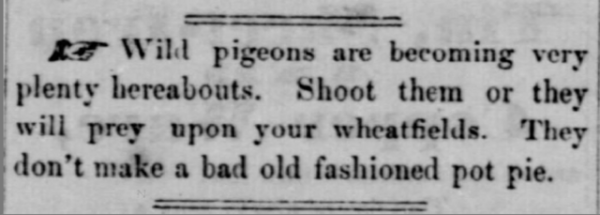

Pigeons were commonly used as a part of meals as their meat was easy to harvest in the rugged terrains of the land. It was common to eat foods like pigeon pie. However, it didn’t help that pigeon meat was commercialized as cheap meat. This caused the demand for pigeon meat to increase, as many could easily purchase pigeon meat for food. The vast population of pigeons meant that they were a stable source of food for many. Pigeons would be hunted and shipped to major cities to be sold for large profits.

Pioneers weren’t the only ones who hunted these birds — farmers did too. Passenger pigeons –like many birds – had a diet made up of nuts, fruits, insects, seeds and grains. As people continued to settle in the passenger pigeon’s native habitat (a combination of mixed hardwood and eastern deciduous forest), farmers started to grow wheat, buckwheat, and maize. These farmers often killed off the pigeons who ate their crops. But, it wasn’t just one or two birds. It was hundreds.

Passenger pigeons were never found alone. A massive flock of them could be found in one tree, looking more like leaves than birds as there could be 100 nests in a single tree. The hundreds of squabs would quickly learn how to fly and leave the nest. Due to the mass amounts of pigeons, it wasn’t uncommon to see many in fields pecking at the wheat the farmers were growing.

The pigeons had to deal with the effects of pioneers, farmers, and hunters, with the most devastating blow being habitat loss. Trees were cut down to make room for towns, and passenger pigeons became the target of hunters.

What was once the most common bird in North America, with a population in the billions, was then left to a few hundred.

Efforts were made to try to conserve the population of the pigeon. In 1857, a bill was brought forth to the Ohio State Legislature seeking protection for the passenger pigeon. A select committee of the Senate filed a report stating, “The passenger pigeon needs no protection. Wonderfully prolific, having the vast forests of the North as its breeding grounds, traveling hundreds of miles in search of food, it is here today and elsewhere tomorrow, and no ordinary destruction can lessen them, or be missed from the myriads that are yearly produced.” They could not be more wrong.

Conservation efforts were largely ineffective: laws were either hardly enforced, or simply not passed. A bill was passed in the Michigan legislature making it illegal to net pigeons within two miles of a nesting area, but this law was weakly enforced. By the mid-1890s, the passenger pigeon had almost completely disappeared. In 1897, a bill was yet again introduced in the Michigan legislature, this time asking for a 10-year closed season on hunting passenger pigeons. Despite this bill passing, this attempt was also unsuccessful, as the measly number of birds that were still alive did not have the capacity to reestablish the population.

Passenger pigeons required large flocks for protection, as the massive amounts of birds greatly outnumbered their predators (foxes, wolves, hawks, and weasels) to the point where little damage could be done to the flock. The pigeons also required large flocks for breeding. They could not survive in small flocks, and their breeding habits required a large population to survive.

The remaining passenger pigeons could not adapt fast enough to their changing world. Their homes were being destroyed. The trees that kept their nest safe were being toppled down to make way for fields of crops which they were killed for eating. The pigeons were shot out of the sky for food and cheap meat.

By the 1900s, the passenger pigeons were facing the end of the line with only a few thousand remaining in the wild.

The remaining few were sold to zoos and private collectors, displayed to the people that led to the downfall of their species. The last recorded passenger pigeon in the wild was shot in 1900.

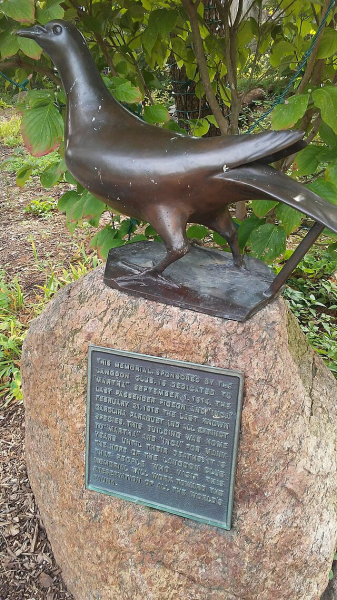

On September 1, 1914, at around 1 p.m., Martha, the last remaining passenger pigeon, died in the Cincinnati Zoo at the age of 29. Her two male companions died in the same zoo in 1910, leaving her as the last of her kind until that fateful day, when the passenger pigeon went extinct.

It’s been a hundred and eleven years since Martha’s death, and the passenger pigeon has never been spotted since. Yet, through the potential of genomic intervention, projects have sprung up to revive them.

Revive & Restore is a wildlife conservation organization that began The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback Project in 2012. The organization plans to compare genomes of the passenger pigeon and the band-tailed pigeon, a close relative to the passenger pigeon. They hope to edit the genome of the band-tailed pigeons to recreate a passenger pigeon.

This method is done in multiple phases, starting with the sequencing and assembling of a genomic code from DNA molecules extracted from the tissues of a band-tailed pigeon.

The same will be done with the DNA from preserved passenger pigeon skin, allowing for the fragments to be mapped to the band-tailed pigeon genome. Differences between the two will be identified and the band-tailed pigeon genome will be edited to match the passenger pigeon genome.

This method will be used with band-tailed pigeon Primordial Germ Cells (PGCs) – an embryonic stem cell that becomes sperm and eggs in adult birds. The cells will be extracted and grown in a culture before the genome editing process begins.

Afterwards, the genome-edited PGCs would be injected into a developing rock pigeon embryo’s circulatory system, allowing for them to migrate to the reproductive organs. The result will turn the rock pigeon into a chimera containing the new passenger pigeon cells in its reproductive organs. Once a male rock pigeon chimera and a female rock pigeon chimera breed, the result will produce the first generation of the de-extinct passenger pigeon.

This process is still being researched as the steps involved are still theoretical and being discussed.

Professors and researchers that are dedicated to sharing the story on the passenger pigeon also emphasize the importance of conserving wildlife. Dolly Jørgensen, a professor of History at University of Stavanger in Norway and co-editor in Chief of Environmental Humanities, is one such person dedicated to sharing information on extinct species.

In an interview that I conducted with her, Professor Jørgensen answered many questions about her research on passenger pigeons and the history behind them.

“I worked on my book Recovering Lost Species in the Modern Age: Histories of Longing and Belonging (MIT Press, 2019), which includes my research on the passenger pigeon’s extinction, for about six years. I started thinking about it when I ran across a TEDx de-extinction event in 2013, and the passenger pigeon was mentioned there as a species that could be brought back to life.” This was in response to my question regarding how long it took her to research the passenger pigeon.

She also answered questions on the main cause of the passenger pigeon’s extinction. On this question she states that, “They were mercilessly hunted every year, and hundreds of thousands would be killed each season. While it’s possible that they ended up with a big die-off event at the end (at the time people thought hurricanes were to blame), it was the hunting pressure that made the biggest dent in their numbers. Clearances of the forests as the Midwest was settled by white settlers certainly didn’t help.”

Not only did she claim that hunting is the primary reason for this species extinction, but she also added in a very unknown fact about what the people of the time thought about the decline of the pigeon. This insight gives more explanation on why people in the past did not enforce larger conservation efforts. If the people thought it was a natural course, like hurricanes, killing off the pigeons, they had no reason to step in.

However, Jørgensen noted efforts to try to breed the remaining pigeons left in a last attempt to conserve the species. On this she said, “That there was an attempt to breed passenger pigeons in the late 1890s, because they could see that they were disappearing. I think the article by R. W. Shufeldt detailing the abduction of Martha was pretty startling.”

Another detail that she highlighted was that many people in the late 1800’s, specifically in 1890, just started to realize that the most common bird to see in the country was declining in population. “What I saw was that by the 1890s, people started asking what had happened to the pigeons, because they didn’t see them very often. So when Martha died in 1914, the passenger pigeon was already functionally extinct.”

As Revive & Restore continues their attempt on reviving the passenger pigeon, Jørgensen had thoughts on the attempts done by other such restoration proposals. “I think that people can modify the genes of animals to create ones that mimic the appearance of extinct animals. It is highly likely that animals touted as passenger pigeon 2.0 or wooly mammoths will exist within the next 20 years. But of course that does not mean that the species is really revived. Species are more than genes – they are lifeways – and nothing a scientist will do in a lab will bring back their lost lifeway.”

The extinction of the passenger pigeon is a reminder of the effects humans have on wildlife. It’s a story painted over and over again.

In 2010, the Alaotra grebe, found in Madagascar, went extinct. The bird was 9.8 inches long with a diet composed of fish and insects. Due to its breeding habits being undocumented, it was nearly impossible for conservation groups to restore the species.

The Alaotra grebe went extinct from habitat loss, a direct consequence of humans encroaching on their habitat. Just like the passenger pigeon, the grebe went extinct from similar factors.

Another species, the Alagoas foliage-gleaner, suffered the same fate. In 1988, its status was listed as near threatened, and in 1994 its conservation status was critically endangered. The Brazilian bird was officially declared extinct in 2011 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The remaining two sites where the species lived were in the reduced Atlantic Forest found in South America. The forest has been almost totally cleared as of 2015 for timber, charcoal, grazing, and sugar cane production. What is left is threatened by illegal clearing, forest fires, and the warming effects of climate change. History repeats itself quite often and these two extinct birds have great similarities with the story of the passenger pigeon.

Other birds have recently gone extinct and many are near extinction such as the California condor. As the United States largest terrestrial bird, the California condor was once extinct in the wild in 1987. The California condor is endangered due to a combination of factors, including lead poisoning, habitat loss, and human activity. The recovery of this species has been slow because of their extremely slow reproduction rate. Female condors lay only one egg per nesting attempt which is not guaranteed to happen once a year. This combined with the 6-8 years it takes a condor to reach maturity is leading this great bird to be critically endangered.

Jørgensen not only did research on the extinction of the passenger pigeon but she also did research on many other extinct birds. “In my forthcoming book Ghosts Behind Glass: Encountering Extinction in Museums (which will be published by University of Chicago Press later in 2025), I discuss the extinctions of many birds: great auks, Carolina parakeets, ivory-billed woodpecker, paradise parrot, moa, elephant bird, dodo, and some others.” All of these extinct birds share similar stories in how humans have led to their extinction.

The Convention on Biological Diversity estimated that, “Every day, up to 150 species are lost.” This drastic number is primarily due to the effects humans have on nature. The past mistakes seen with the passenger pigeon still occur to this day.

Many researchers claim that because of the mass amounts of animals being lost, the world is currently in its sixth mass extinction. “Unfortunately there are lots of species whose numbers are decreasing dramatically because of climate change, habitat loss, and hunting. The Sixth Mass Extinction is ongoing.” Jørgensen stated near the end of my interview.

She warns that, “Humans have to be willing to share the planet with others. The fantastic diversity of life on Earth has taken millions of years to develop, but it will take hundreds to crush it if humans don’t act differently. Every loss of a species because of human action is a thread cut that could lead to the unravelling of the tapestry of life.”

As human populations increase, more and more resources are used to support the growing number of cities and towns. This results in drastic amounts of habit loss as land is cleared away for more farms and towns. Trees are cut down to be used for resources while pollution increases due to the sheer amount of waste produced by over 8 billion people.

This is a perfect example of the domino effect, with the first domino being pushed down by humanity. The pigeons have been crushed by these metaphorical dominos. As a result, passenger pigeons serve as a reminder of how a great, prosperous species can be ravaged until nothing remains.

“Humans have to be willing to share the planet with others. The fantastic diversity of life on Earth has taken millions of years to develop, but it will take hundreds to crush it if humans don’t act differently. Every loss of a species because of human action is a thread cut that could lead to the unravelling of the tapestry of life,” said Dolly Jørgensen, a professor of History at University of Stavanger in Norway and co-editor in Chief of Environmental Humanities.