Dressed in handsome green, he slips through the cracks of everyday life. But spotting him inevitably raises an eyebrow, if not starting a conversation outright.

Nowadays, finding a $2 bill can feel like stumbling upon the directions to El Dorado. Featuring the third U.S. president, Thomas Jefferson, the $2 bill has been affectionately nicknamed Tom. Most people encounter Tom so infrequently that they assume there are not many $2 bills out there. Yet, many Americans may be surprised to learn that this bill is not scarce at all — over 200 million Toms were printed in 2024. Nevertheless, they make up the smallest percentage (3%) of actively circulating currency.

“My mom always keeps a spare $2 bill in her wallet for good luck, and she says she’ll never use it,” said Olivia Kim ’28.

This strange fascination surrounding an otherwise ordinary bill can be traced back to its eccentric history. For the better part of its existence, the $2 bill has been linked to the seedier sides of our society. Only in the last half-century has the bill taken its rocky road to redemption. Regardless, most Americans remain misinformed about its history and significance.

So why is the $2 bill so misunderstood?

Troubled Beginnings

The first $2 bills are older than our nation itself. On July 25th, 1775, the Second Continental Congress issued paper bills — including $2 notes — known as Continentals in order to support the Revolutionary War effort. However, Continentals soon became worthless because they weren’t backed by any physical assets. Once people caught wind that the bills couldn’t necessarily be exchanged for gold or silver, Continentals became a thing of the past.

$2 bills as we know them did not come about until 1862. These 1862 “legal tenders” featured Jefferson on the front, the same portrait we see today. The reverse side of the bill was decorated with a painting of Monticello, Jefferson’s estate in Virginia.

But $2 bills did not have a steady start. Over the first few years of printing, paper currency was still a novelty, and many people had not yet made the transition away from coins. After years of slow adoption, Tom was still considered the odd man out, by technology and chance. James Ritty, an Ohio bar owner, suspected his troublesome bartenders were swiping profits. In 1879, he patented the first ever cash register. Five years later, Ritty developed a next generation model that was equipped with a nifty cash drawer for storing bills. However, the drawer was only wide enough for five slots which he assigned to $1s, $5s, $10s, $20s, and $100s. $2 bills were left by the wayside.

Then, in the 1930s, the country faced the deepest economic downturn in its history. During the Great Depression, the cost of the majority of goods and services was a dollar or less, and most people only had that much to spend, which made the use of a $2 bill less frequent. Even as the economy recovered, Tom was left in a strange position. Inflation brought the value of the dollar down so the incremental difference between $1 and $2 became narrower. With two bills so similar to one another, people had little use for both.

Tom’s Bad Rap

When the $2 bill was in the spotlight, it was for all the wrong reasons.

For a time in the late 1800’s, $2 bills were the face of crooked politics. As municipal and state voter turnout rose, so did election fraud. Corrupt politicians often bribed voters with $2 for a vote. Having a Tom in your wallet – even an innocent one – could be seen as evidence that you had sold your ballot.

The $2 note also symbolized various social taboos, namely prostitution and gambling. Throughout the Roaring Twenties, Ladies of the Night charged $2 for their services, while $2 was the standard bet on horse races.

If the bill’s scandalous settings were not enough, the number that adorned it was even more notorious — the word “deuce” was a nickname for the devil. The $2 bill went from something that was simply shameful to a bearer of bad luck. A 1925 article from The New York Times states, “He who sits in a game of chance with a two-dollar bill in his pocket is thought to be saddled with a jinx. The only place where it is supposed to consort happily with Lady Luck is at the race track where, strangely, it is relied on to bring good fortune.”

For the few who did not abandon their twos entirely, one popular way of “reversing the curse” was by tearing off the corner. Though we cannot say for sure if this preserved the owner’s good fortune, Tom certainly did not get any luckier. The mutilated currency was deemed unfit for circulation, and scores of $2 bills had to be returned to the U.S. Department of Treasury.

By 1966, the Federal Reserve was left with no choice. The $2 bill got along so badly with Americans that production was cut off entirely, with no resume date in sight.

First is the Worst, Second is the Best

The $2 bill could have easily been thrown into the dustpan of history, but it was not long before the Treasury began to miss the Tom. Despite not being popular with the public, printing $2 notes actually saves the government money. Today, it costs the same 3 cents to print a $1 bill as it does to print a $2 bill, so the Federal Reserve can print half as many twos to put the same dollar amount into circulation.

With that realization, Tom got a new lease on life. On April 13th, 1976 — in honor of Jefferson’s birthday — the Federal Reserve put in an order to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for a whopping 400 million $2 bills.

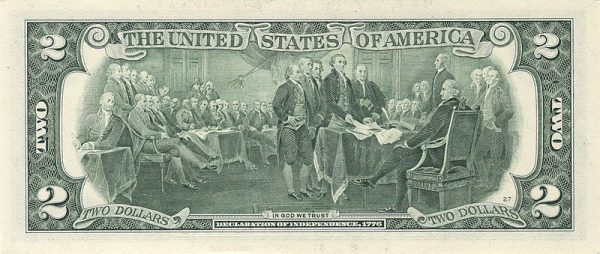

Not only was the Deuce back, but he was back in style. The new bills were brighter and crisper, with a fresh green ink for the seal and serial numbers. The renewal of the $2 note also happened to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, so the Federal Reserve gave the bills a spiffy bicentennial-themed redesign. The backside was replaced by John Trumbull’s painting of the drafting of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson was seen front and center, presenting the draft to Congress. It turned out perfect — perhaps a little too perfect.

Americans loved the beautiful, new look. Many people mistook the updated bills as limited edition prints that would only be available as part of the bicentennial festivities. Some were even unaware that the bill had officially been reissued. After their decade-long disappearance, the sudden re-emergence of $2 bills led many to believe that the ones they came upon had somehow slipped through the cracks of the Fed.

In a 1981 interview with The New York Times, then-Director of the Bureau of Engraving Harry R. Clements said, “I’m afraid we don’t have any good, rational explanations. It [the $2 bill] seems to be one of those things that the public just couldn’t become accustomed to.”

So, rather than using them for everyday transactions, people began to hoard their supposed “collector’s item.” Instead of making their way into shops like the government had hoped, the new $2 notes were tucked away in the safes of American homes.

Thus began the myth of the “ultra rare” and “auspicious” $2 bill. The more people held onto these bills, the fewer were seen in circulation, and the more special they appeared. Nearly 40 years later, the oddity of $2 bills leaves Americans in the dark about their status as actively issued currency. Meanwhile, people still hang onto their $2 bills for good luck.

“When I turned eight, I received a $2 bill from my grandfather for my birthday. Less than three days later, I lost it, but the sentiment stuck with me,” said Cooper Halpern ’27. “My dad gave me ten $2 bills because he realized how fascinated I was with them — the fact that it’s money that can’t be found anywhere, that hasn’t changed hands time and time again! Every day since, I’ve kept one of those original ten $2 bills in the back left sleeve of my wallet.”

Tiger Twos

Clearly, the second attempt at bringing the bill into day-to-day transactions fell short of its goal. But that has not stopped it from being the heart of many beloved traditions. Take the Clemson “Tiger Twos.”

Since 1898, the Clemson University Tigers and Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets have been embroiled in an epic football rivalry. Each year, over 15,000 Tiger fans excitedly make the trip down to Atlanta for the big game.

Devotees of the Tigers are not the only ones that look forward to the annual face-off, as local Atlanta business-owners welcome the visitors with open arms. But in early 1977, Georgia Tech abruptly decided to cut Clemson off by refusing to renew their contract. The news left Clemson fans up in arms.

Before the contract expired, the Tigers and the Yellow Jackets were scheduled for one last showdown that September. Amidst the lingering outrage, Clemson was looking for a way to make their longstanding rival regret their decision. Enter George Bennett, Clemson class of ’55 and Executive Secretary of Clemson’s athletics fundraising program. In the weeks leading up to the game, Bennett devised a clever plan to prove just how much the local economy of Atlanta benefited from the Clemson community each year.

Bennett urged all the Tiger fans at the game to use $2 bills for every expenditure. The rarely circulated bills were just what they needed to make a statement. Receiving a $20 bill would be nothing out of the ordinary, but ten $2 bills were impossible to ignore. Every time Atlanta businesses saw the unusual bill, they could envision how much money they would be losing out on in the future.

Sure enough, the Tigers covered the city in Toms. Waiters, cab drivers, bartenders, doormen, and store-owners all began to receive these bills en masse. People even paid for their hotel rooms in $2 bills. The arrival of the “Tiger Twos” became a spectacle featured even in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and local television networks. After a brief hiatus, the Clemson vs. Georgia Tech game returned in 1983.

The story was such a hit that it has stuck with the team for nearly 50 years. Supporters make an even bigger show of their Clemson pride by stamping their bills with an orange tiger paw. To this day, fans stuff their wallets with twos for the university’s away games, reinforcing the most unique tradition in college football.

On a smaller-scale, other organizations have similarly raised awareness through “SpendTom” campaigns that leverage the power of the two. For instance, in 2010, the California Travel & Tourism Commision distributed nearly 100,000 $2 bills across the state to demonstrate the importance of California’s tourism industry.

Nifty or a Nuisance?

Americans still grapple with whether to let the $2 bill remain a mystery or to give it a place in daily life.

On the one hand, inflation may make $2 bills a better option. With prices still 21% more expensive than pre-pandemic, twos might be getting closer to becoming a ”single” in terms of purchasing power. Even dollar stores are not strictly “dollar” stores anymore; in 2024, Dollar Tree raised its minimum price to $1.50 and expanded the number of items that are priced up to $7.

On the other hand, some argue that using $2 bills is more trouble than it is worth. According to one veteran bank teller, asking for twos at the till can slow tellers down in their usual rhythm of counting out cash. Moreover, inexperienced bank tellers may have never dealt with $2 bills and assume they are fake or misprinted.

When people use $2 bills, businesses that end up with them often bring them to the bank, leading to a pileup that does not get circulated again until someone asks for them.

The twos that do make it out into the world can cause confusion as well. For instance, in 2016, eighth grader Danesiah Neal was threatened with a felony forgery charge on the school lunch line after paying for her chicken nuggets with a $2 bill that her grandmother had given her. She told ABC-13, “I went to the lunch line and they said my $2 bill was fake. They gave it to the police. Then they sent me to the police office. A police officer said I could be in big trouble.”

With the lofty price of $2 chicken nuggets at stake, local police called Danesiah’s grandmother and traced the bill to the convenience store that handed her the change. Unsurprisingly, the 13-year-old was not committing third-degree counterfeiting. The bill was simply so old, a 1953 edition, that it incorrectly triggered the school’s counterfeit pen.

Until $2 bills are accepted for what they are — nothing more and nothing less — mishaps like these are sure to continue. Will Toms continue to be an enigma or gradually become as commonplace as Washingtons and Lincolns? Whatever their fate may be, $2 bills certainly have the most interesting track record of any U.S. currency.

The more people held onto these bills, the fewer were seen in circulation, and the more special they appeared. Nearly 40 years later, the oddity of $2 bills leaves Americans in the dark about their status as actively issued currency.