As July 26th, 2024 approaches and temperatures rise, the 2024 Summer Olympics will soon be upon us. For the first time in exactly 100 years, Paris, the ‘City of Lights,’ will host the highly-anticipated games. The French people are in a frenzy preparing for the festivities and readying themselves for over fifteen million tourists.

Yet, the spirit of this year’s Olympics has already been dampened by brutal world conflicts. The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine that began in February of 2022 is the largest war on the European continent since World War II. Meanwhile, partly overshadowing those tensions is the current Middle East situation with the Israel-Hamas war and the human tragedies unfolding in Gaza. These wars have not only wreaked havoc on those regions, but also initiated intense polarization around the world arousing protests in the streets and on college campuses. So before we delve into the games of the XXXIII Olympiad, perhaps now would be a good time to review the Olympic Protest Rule.

According to the controversial Rule 50 in the Olympic charter, “Every kind of demonstration of propaganda, whether political, religious, or racial, in the Olympic areas is forbidden.” To the surprise — and outrage — of many, this rule has weathered the ever changing sociopolitical climate since its inception in the mid-1970s, and it has not stopped the many athletes who have come head-to-head with entire nations to confront the pressing issues of their day.

We have seen countries protest the host nation by boycotting the games, such as the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics. However, athlete protests represent a different kind of boldness — the courage to make a statement as an individual for an audience of billions. For athletes seeking to grab the attention of world leaders and global citizens, there is no greater opportunity to do so than the Olympics.

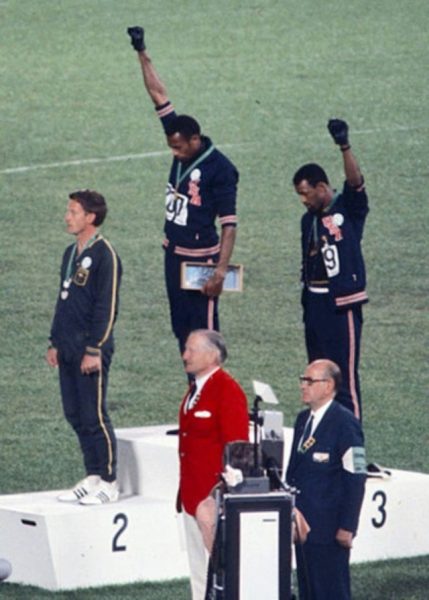

Smith, Carlos, & Norman: Mexico City, 1968

The 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics fell on a particularly tumultuous year in U.S. history. The assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy in June as well as the unyielding discord over the Vietnam War made for an era of fervent unrest. Racial tensions were at an all time high and the decade’s Civil Rights movement gave rise to the Black Power movement. On top of the chaos, the games had to be postponed to mid-October due to the unbearable heat in Mexico City that summer, leading it to be dubbed “The Problem Olympics.”

Where others saw a mess, two African-American sprinters saw an opportunity. Dissatisfied with the Civil Rights Movement that they deemed unassertive, 24-year-old Tommie Smith and 23-year-old John Carlos sought to fight for change in more dramatic ways. In preparation for the Olympics, Smith and Carlos formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Their mission was to utilize the upcoming games as a platform for defiance against the mistreatment of Black people and other marginalized communities around the world, especially in the sphere of athletics. On the afternoon of October 16th, 1968, Smith and Carlos raced their two-hundred-meter final and won gold and bronze respectively. White Australian sprinter Peter Norman took the silver medal in a surprising upset just before the finish line.

As the three athletes prepared to rise to the podium, the American sprinters let Norman in on their plan; Smith and Carlos would go without shoes to represent Black poverty, wear beads to cry out against lynchings, and raise black-gloved fists to symbolize Black power and solidarity with oppressed peoples everywhere. Norman — devout to the Salvation Army faith and its principles of human equality — was more than willing to be a part of their statement. Carlos would later tell the New York Times, “Pete became my brother at that moment.”

They were quickly rushed off the stage, evicted from the Olympic Village, and suspended from their respective Olympic teams. Though Rule 50 did not exist yet to forbid protests at the event, the bold act cost the athletes their international careers. For nearly 50 years, Smith and Carlos were ostracized by the Olympic community and shut out of events by the U.S. Olympic Committee. Although Norman continued to outperform sprinters across Australia, he was also fiercely punished by the Australian sporting establishment and snubbed numerous times of a rightful place at future Olympic Games.

All three sprinters received a flood of backlash, ranging from criticism in the media to personal death threats. Norman fell victim to depression, alcoholism, and addiction. Smith attributed his divorce to the toll that the public abuse took on his marriage. Just two days after the protest, the L.A. Times wrote, “Tommie Smith and John Carlos do a disservice to their race — the human race.”

Nevertheless, the deed was done. The 1968 games were the first Summer Olympics to be broadcasted live and in color on TV, as well as the first to ever feature instant slow-motion replay. As such, the athletes demonstrated for the largest ever audience with hundreds of millions tuned in worldwide. The mere minutes that Smith, Carlos, and Norman spent on stage had sent an irreversible shock wave through America, bringing light to the Black Power movement and inspiring other civil rights activists around the globe.

Their iconic salute and its accompanying message brought an even longer-lasting legacy to the Olympic guidelines — the provocation of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1975 to adopt the first official protest rule into its charter — the roots of Rule 50.

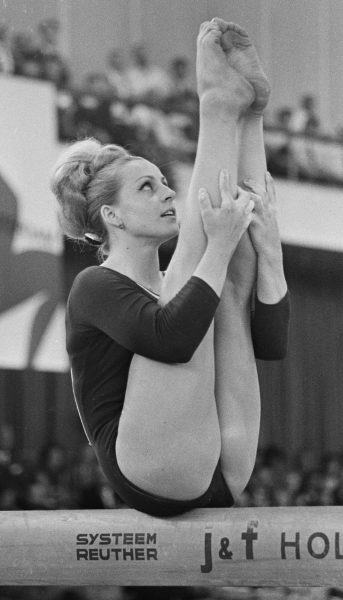

Věra Čáslavská — Mexico City, 1968

Although often outshined in history by the Black Power protest, a quieter yet equally impassioned demonstration simultaneously took place on the mat during those games.

Born in 1942, Věra Čáslavská was an iconic Czech gymnast and the most successful female gymnast worldwide in the 1960s. From the age of 16, she had already built an international sporting career that only grew when she became an Olympic athlete. At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, her gymnastic expertise won her four medals and the Japanese nickname “オリンピックの名花” (“darling of the Olympic Games”). To this day, she holds the remarkable distinction of winning the most individual gold medals amongst all female athletes in Olympic history.

Beyond her astounding success in gymnastics, Čáslavská was renowned for her defiance against Soviet puppeteering and her vocal advocacy for a Czechoslovakian democracy. Hers was one of the signatures on The Two Thousand Words, a manifesto urging for the rapid democratization of her country.

In the summer of 1968, just as the U.S. was experiencing its own turbulence, Czechoslovakia suffered invasions from the USSR and other Warsaw Pact countries. In an attempt to suppress growing calls for liberalization and reform, Soviet tanks killed hundreds of civilians in the streets of Prague. Čáslavská, fearing for her safety, fled to a remote rural location where she trained for the upcoming Mexico City Olympics. In anticipation of going head-to-head with Soviet competitors, she vowed that she would “sweat blood to defeat the invaders’ representatives.” It was safe to say that the 1968 Olympics represented something more for Čáslavská, something much deeper.

Her isolation from a proper training facility did not diminish her triumph at the games. In all six events, Čáslavská won gold and silver medals, but she had not achieved her mission entirely. In the floor competition, she earned a score of 9.9 out of 10, a number that should have earned her an outright win. However, in a bizarre scoring revision, the judging panel upgraded the scores of Larisa Petrik, a Soviet gymnast. The judges declared a tie between the two, and Čáslavská was forced to share the gold.

Demoralized by the slanted decision that favored the Soviet Union, the athlete hoped to deliver her own message, nine days after Smith and Carlos had given theirs. As the Czech and Soviet flags were raised, Čáslavská and Petrik stood side-by-side on the podium listening to the Soviet anthem. Čáslavská made a silent but courageous gesture by turning her head down and away as a form of resistance.

Upon returning home, Čáslavská was the beloved heroine of the Czechoslovakian people. Her government on the other hand, still under Soviet influence, felt otherwise. Her demonstration and ongoing dissent from the communism of the USSR cost her dearly. Čáslavská lost her freedom and essentially her career as she was barred from traveling both outside and within the country. The seven-time gold medalist was effectively forced into retirement.

In an interview with BBC Sporting Witness, Mary Prestidge — a fellow gymnast at the 1968 Olympics — recalled, “She was seen to be much more than just a gymnast or a sportsperson. She carried that in her performance and who she was as a person. The two were tightly together and she never undermined one for the other. She was going to be champion of the world and not sign away her political allegiance either… bravo!”

An Ongoing Dilemma

As the decades have passed, athletes, officials, and viewers worldwide continue to debate over what place, if any, social and political protests should have at the Olympics.

Some advocates of Rule 50 believe that protests blemish the spectacular accomplishment of getting to the Olympics. Athletes spend years training for this occasion, and protests detract from this celebration of their hard work. In the lead-up to the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, the Daily Titan of CSU wrote, “Athletes have earned the undivided attention of viewers, fans and family to focus solely on their achievements in their respective event, without additional political factors and displays.”

Others consider the ban on protests as a way to protect the neutral sanctity of the games. According to a 2020 statement from the IOC, “the political neutrality of the Olympic Games is a way to protect athletes from political interference or exploitation.”

Current IOC President Thomas Bach is no stranger to protest himself. The former athlete was an Olympic gold medalist for the West German fencing team in the 1970s and ’80s. In the U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, 65 nations protested against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by withdrawing from the games. Bach represented West German athletes in the deliberation over whether the country would join the boycott.

Many athletes, Bach included, wished to ignore the protest and compete as planned. However, public opinion ultimately outweighed these sentiments and West Germany withdrew from the Moscow Games. Four years later, the Soviet Union led their own retaliatory boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, removing athletes from the playing field once again. To this day, the president of the IOC looks back with sorrow for the athletes that missed their chance because of these protests, which has largely inspired his vision of a depoliticized Olympics.

“The boycott of Moscow achieved nothing at all. And this has been admitted also by all the major actors, at least in Germany, who were there at the time, who already a couple of months later in conversations told me, ‘We made a mistake. This was not the right thing to do,’” said Bach in an interview published by the IOC.

He continued, “So there, anybody who is thinking about a boycott should learn this lesson from history; a sports boycott serves nothing. It’s only hurting the athletes, and it’s hurting the population of the country because they are losing the joy to share, the pride, the success with their Olympic team.”

Meanwhile, critics of the rule find that the right to protest at the games is precisely what Olympic athletes need. Having reached such an esteemed position in the sporting world, athletes certainly have the right — and perhaps a duty — to use their platforms to speak out on political or human rights issues. In an open letter to Bach, the World Players Association wrote, “We are confident that sport and society have reached a historic turning point where the athlete voice is celebrated and embraced, even in previously reluctant corners.”

Tokyo, 2021

The 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics (postponed to 2021 due to COVID-19) marked perhaps the greatest turning point in Olympic history with regards to Rule 50 since 1968 and the rule’s creation.

2020 brought a new height to social unrest, especially as tens of millions of people joined in protest for the Black Lives Matter movement. During this period, attitudes towards athlete activism began changing more rapidly than ever before. Yet, the Olympic protest rule stood startlingly still.

Amidst mounting pressure to reform the rule, in 2021 the IOC finally announced a revised Rule 50. Athletes are now permitted to “express their views” through demonstrations during interviews and on the field of play prior to the start of the competition. A small but significant change, the update symbolized a huge concession to protestors; restrictions have finally relaxed after over 40 years of maintaining the unwavering framework of 1975.

The Tokyo Games that followed served as a stage for global viewers to witness in action the massive influence of these revisions.

The first demonstration that year was delivered by American shot-putter Raven Saunders. After accepting her silver medal, Saunders raised her arms above her head in the shape of an X. The athlete described the gesture as a representation of unity with oppressed people. For Saunders personally, the X illustrated solidarity and intersection between communities that she is a part of. Her motion was a message on behalf of Black and LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as those who have survived mental health struggles.

This time, the protest was far from isolated. Athletes in other sports, such as U.S. Olympic fencer Race Imboden, joined Saunders in the demonstrations. Imboden similarly appeared during his medal ceremony with an X. The circled X symbol on the back of his hand caught the public eye even faster than the polished, bronze medal he held.

The fencer later tweeted, “For me I personally wore the symbol as a demonstration against rule 50. In support of athletes of color, ending gun violence, and all the athletes who wish to use their voice on the platform they’ve earned.” He added that he wished “to draw attention to the hypocrisy of the IOC, and all of the organizations who profit so immensely off the athletes and have yet to hear their call for change.”

In gymnastics, 18-year-old Luciana Alvarado — the first Costa Rican gymnast to qualify for the Olympics — ended her spectacular floor routine by taking a knee and raising her right fist. Though the updated Rule 50 still bans protests during competition, Alvarado found a loophole by incorporating the gesture as an artistic element of her routine. Meanwhile, in soccer, left winger Megan Rapinoe and the rest of the U.S. team took a knee just before kickoff in their game against New Zealand.

Paris, 2024

What is to come in this year’s Summer Olympics, running from Friday, July 26th through Sunday, August 11th, 2024?

Amidst the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine and Russia’s involvement in doping scandals at previous Olympic Games, the country has stood on shaky ground with the Olympics Committee. Over the last decade, many have voiced calls for Russia to be kept out of global sports — the Paris Summer Olympics being no exception.

Following months of restless anticipation, Bach announced in December 2023 that individual Russian athletes would in fact be permitted to participate in the games after thorough vetting to confirm their political neutrality. The governing body of each sport will be responsible for evaluating the neutral status of competitors, ensuring they have not supported the war nor been involved with the Russian military or state agencies. The IOC states that these procedures will qualify only a limited number of athletes to compete. Those who have proven their neutrality must participate without their national flag, colors, or anthem.

Since then, the IOC has been met with outrage from both sides of the war. Some Russian officials have denounced the committee for “politicizing” the games through this investigative process. Others have accused Bach and the IOC of conspiring with Ukraine to exclude Russia’s strongest athletes.

On the other side, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and others see it as an excessively lenient policy. In a 2023 video address, President Zelenskyy stated, “It is obvious that any neutral flag of Russian athletes is stained with blood.” Ukrainians and many others worldwide have denounced the IOC and its decision to trivialize the fierce war.

Without a doubt, the 2024 Paris Olympics will guide a scene of rejuvenated, fiery discourse over whether Rule 50 belongs in the Olympic charter. Against the backdrop of troubling world events, this year’s games will bring athlete protest to the forefront once again. How heavily Rule 50 is enforced will depend in part on the court of public opinion globally. Until then, we will be left to wonder: who will be called to the stage next?

For athletes seeking to grab the attention of world leaders and global citizens, there is no greater opportunity to do so than the Olympics.

![The Olympic Games have long been intertwined with athlete protests. Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and Peter Norman’s 1968 protest is recognized as one of the first and most groundbreaking demonstrations in Olympic history. [Photo Credit: Angelo Cozzi (Mondadori Publishers), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]](https://thesciencesurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Peter_Norman_John_Carlos_Tommie_Smith_1968.jpg)