Sahelanthropus tchadensis, commonly known as Toumai, stands as a significant milestone in our understanding of human evolution. Approximately 7 million years ago, these now extinct hominids gloriously roamed the Earth during the Miocene epoch. Now, however, they only remain to offer invaluable insights into our ancestral past. Considered our oldest known ancestor after the human lineage split from chimpanzees, Toumai’s discovery has greatly enriched the study of human origins.

Background of Discovery

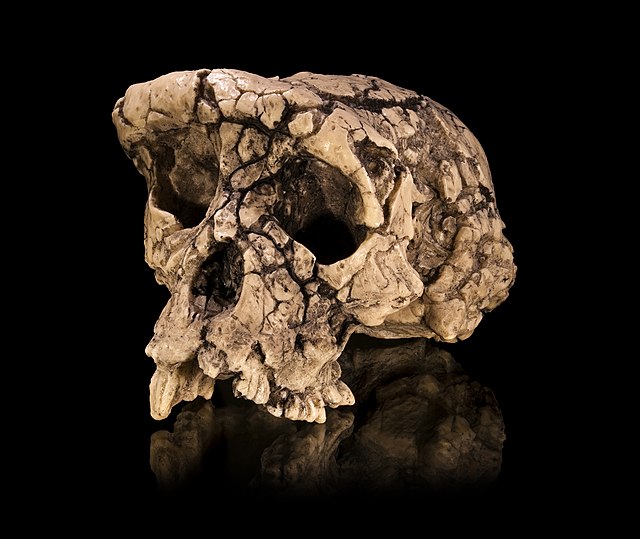

The remains of Sahelanthropus tchadensis were unearthed by a team led by Michel Brunet, a French paleontologist, between July 2001 and March 2002 in the Djurab desert of Chad, Africa. The fossils, identified with numbers starting with TM 266, include several jaw pieces, teeth, and a small but relatively complete cranium nicknamed Toumai, which means “hope of life” in the local language. The genus name “Sahelanthropus” is derived from “Sahel,” referring to the area of Africa near the southern Sahara where the fossils were found, and “anthropus,” based on the Greek word meaning “man.” The species name “tchadensis” honors Chad, the country where the specimens were recovered. Thus, the name translates to “the Sahel man from Chad.”

Up until this day, all fossils of Sahelanthropus tchadensis have been recovered from the Toros-Menalla site in the Djurab desert of Chad, Africa. So, the cranium numbered TM 266-01-060-1 was made the type specimen (selected as a permanent reference for Toumai) despite being somewhat crushed and eroded by sand.

Other than Toumai, the discovery included other potential hominin bones, such as a left femur (upper leg bone that connects the lower leg bones) and a mandible (lower part of the jaw, the largest and strongest bone in the face). Some debate whether these pieces belong to the same cranial or not. It continues to be a mystery to many.

However, a Taphonomic analysis was done, which is the study of modifications that a biological organism endures from its death to the moment its fossil remains are rediscovered. And it suggests that these pieces might not have been deposited simultaneously. This is a potential indication that the fossils may have been transported from elsewhere and reburied in more recent times. The reasons are unknown and it continues to intrigue researchers.

Age

At the site of the discovery, radiometric dating was not possible due to the absence of volcanic ash layers. Instead, faunal analysis (to identify the kinds of animal remains) was used, leveraging the presence of other fossil animals that had been radiometrically dated elsewhere.

The findings suggest that the Sahelanthropus tchadensis fossils are dated to 6-7 million years old. This time frame places their existence squarely in the critical period, when scientists predict that the human lineage diverged from that of apes. Hence, Sahelanthropus tchadensis fossils are key to understanding the story of human existence as it paves the path for humanity to rise.

Important Fossil Discoveries

The fossils discovered by Brunet’s team are among the most significant early hominin finds. The six fossils include a remarkably preserved cranium, jaw pieces, and teeth. The cranium, although damaged, offers crucial evidence of the species’ anatomy and potential behaviors.

Two other notable bones, a left femur and a mandible, were found alongside the cranial remains. However, their exact relationship with Sahelanthropus tchadensis is debated. The femur, not recognized as possibly belonging to a hominin until 2004, lacks diagnostic features that could confirm bipedalism, a key trait for defining hominins.

Relationships with Other Species

The taxonomic position of Sahelanthropus tchadensis is highly debated. Its discoverers claim it has numerous derived hominin features, making it the oldest known human ancestor after the human-chimpanzee split. Alternative interpretations of Sahelanthropus tchadensis suggest that this ancient hominin may hold various positions in the evolutionary tree. One interpretation posits that Sahelanthropus tchadensis could be a common ancestor of both humans and chimpanzees, providing a crucial link in our understanding of hominin evolution. Another perspective suggests that while Sahelanthropus tchadensis is related to both humans and chimpanzees, it is not a direct ancestor of either lineage, indicating a more complex branching of the evolutionary tree than previously thought. Additionally, some interpretations propose that Sahelanthropus tchadensis may actually be an ancestor of gorillas, challenging the conventional placement of this species within the human evolutionary lineage.

Each of these interpretations highlights the ongoing debates and uncertainties in paleoanthropology regarding the precise role and significance of Sahelanthropus tchadensis in the broader context of primate evolution. The varied hypotheses underscore the complexity of tracing evolutionary relationships and the need for further fossil evidence and advanced analytical techniques to refine our understanding of early hominin development.

Michel Brunet disputes these interpretations, citing a 2005 study where CT scans rebuilt a more accurate picture of the Toumai skull, comparing it to fossil hominins, chimpanzees, and gorillas. The study concluded Toumai fell within the hominin range for over 30 features.

Even if Sahelanthropus tchadensis is not a hominin, its significance remains, as few chimpanzee or gorilla ancestors have been found in Africa. It would also be the best-preserved fossil ape of this age ever found.

Key Physical Features

Based on limited cranial remains, the estimated brain size of Sahlenthropus tchadensis ranges from 320-380 cubic centimeters, which is similar to that of a chimpanzee. This small brain size aligns with early hominin characteristics and provides insight into its cognitive capabilities, though direct comparisons are challenging due to the incomplete fossil record.

Regarding body size and shape, the lack of skeletal remains complicates precise estimations. However, it is inferred that Sahelanthropus tchadensis likely resembled modern chimpanzees in size, offering a useful, albeit rough, reference for understanding its physical form.

The jaws and teeth of Sahelanthropus tchadensis reveal notable features. The species had relatively small canine and incisor teeth, which bear a resemblance to those of Ardipithecus (another genus of extinct hominins from the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene epochs in Ethiopia), though with minor differences. The enamel thickness of the teeth was intermediate between that of living apes and australopithecines, suggesting a transitional dental adaptation. The dental arch was narrow and U-shaped, and the premolars featured two roots. Importantly, there was no lower jaw diastema — a gap typically found in other primates — indicating a closer dental structure to later hominins. The cheek teeth were comparable in size to those of Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus afarensis, other extinct species somewhere between apes and humans, providing further clues to its dietary habits and evolutionary relationships. The conclusion made from this is that their diets were primarily plant-based. It is predicted that the Toumai mostly consumed items such as leaves, fruit, seeds, roots, nuts, and insects.

The skull of Sahelanthropus tchadensis presents a mix of primitive and derived traits. The rear of the skull retains an ape-like appearance, while the position of the foramen magnum (the opening in the base of the skull which joints the spinal cord to the brain) — a key indicator of bipedalism — suggests the potential for upright walking, although this interpretation is debated. Some neck muscle attachment scars indicate quadrupedalism, but others argue they are consistent with bipedalism. The face of Sahelanthropus was relatively flat compared to living apes, yet more protruding than in modern humans, reflecting an intermediate evolutionary stage. The skull base was long and narrow, featuring a prominent brow ridge, a wider upper facial area, and a large canine fossa. The eye sockets were wide, similar to those of apes, and the presumed males had a small sagittal crest and a large nuchal crest, indicating strong neck muscles.

This significant gap in the fossil record prevents definitive conclusions about its ability to move. Without these crucial skeletal elements, it remains uncertain whether Sahelanthropus tchadensis was capable of bipedalism, though some cranial limbs are the least understood aspect of Sahelanthropus tchadensis due to the absence of features suggest it may have had the anatomical capacity for upright walking. This mix of features highlights the transitional nature of Sahelanthropus tchadensis and underscores the ongoing debates about its place in human evolution.

Culture

There is no evidence of cultural attributes, but Sahelanthropus tchadensis might have used simple tools similar to those used by modern chimpanzees, such as unmodified stones or sticks and other easily shaped plant materials.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis, or Toumai, represents a profound chapter in the saga of human evolution. As a bridge between apes and humans, Toumai offers valuable insights into the origins of our species and the complex journey that led to our existence. By studying Toumai and its contemporaries, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of life forms that once inhabited our planet and the remarkable journey that culminated in the rise of Homo sapiens.

This mix of features highlights the transitional nature of Sahelanthropus tchadensis and underscores the ongoing debates about its place in human evolution.