“Kiistónnoon aiitsí’poyio’pa” – We are speaking Blackfoot.

The Blackfoot tribe, native to lands throughout Montana and Alberta, is estimated to have a combined population of 60,000, yet only 5,000 speakers of the Blackfoot language remain.

Across the world, thousands of other Indigenous communities are experiencing similar language degradation. From Australia’s lush forests, home to the Aboriginal people, to the rolling plains of America’s Midwest, one indigenous language across the globe is estimated to die every two weeks. While almost all existing languages are currently at risk, with up to 90% of languages across the world facing extinction by 2100, Indigenous languages have been deemed the most vulnerable by far.

In Indigenous communities, native languages are closely linked to their cultures. Languages are the foundation of identity, encoding traditions and cultural customs. It helps people define and solidify their culture. When taken away, there is very little community left to preserve.

In a globalized world, many Native people have already become assimilated into mainstream culture. They regularly speak English, wearing the latest fashion trends, and move away from their own communities into more urban areas. While this seems to be the natural progression of humans everywhere, Indigenous people leaving their homes uniquely degrades their culture. Due to the fact that Indigenous languages are almost exclusively spoken in more isolated areas, disrupting this isolation makes it extremely difficult for these languages to thrive.

As languages are lost, correct ways to perform customs and other traditional activities are lost, leaving a void in numerous native cultures. Similar to the ways in which many religious traditions need to be performed in a specific language, so do many Indigenous cultural practices. Languages are a tangible expression of self-determination from foreign colonizers, critically important to maintaining the identity and values the group stands for. By expressing themselves, Native peoples can actively repel attempts at assimilating them and keep their communities intact.

A Haunted Past

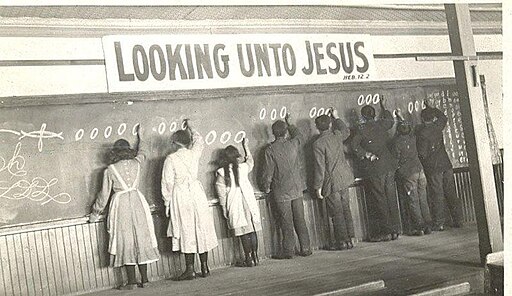

Erasure of Native culture has been the standard since the early colonial period, when European explorers discovered new territories in the Americas and Australia. While the commonly known stories of disease outbreaks and forced labor are horrific in their own right, the stories of cultural genocide, which the effects of are still prevalent today, have been long overlooked. A cultural, or ethnic, genocide consists of a religion, langauge, or culture being targeted instead of human life. In an attempt to assimilate indigenous people, many countries created schools meant to wipe natives of their culture, in an attempt to implement a “white standard.”

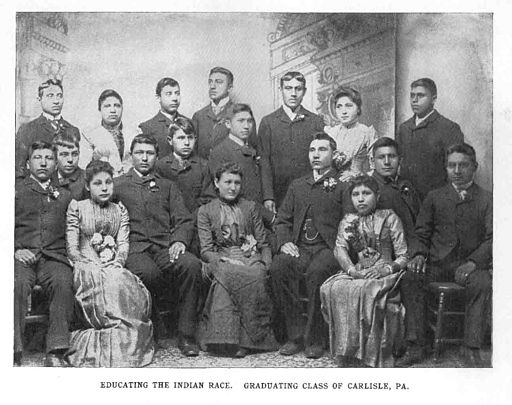

In 1879, the first federally funded “Indian Boarding School” in the United States opened under General Richard Henry Pratt targeting indigenous populations. His mission: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” as stated in his infamous address in 1892. Soon, 523 similar schools spread across the country, almost all of them funded by the government.

These schools quickly became notorious for the abuse and trauma they inflicted upon young indigenous children. In order to get kids to attend, Indigenous children had to be forcibly removed and abducted from their homes. The things that went down inside these schools are just as devastating. Upon arrival at the building, children had their hair cut short, in an attempt to strip them of anything that made them appear Native. Children were also assigned new English names and if heard speaking in their native tongue, faced beatings.

Similar institutions were established all across the world. In Canada, the residential school system functioned just like the American versions, wiping any semblance of their culture from native children. Australia also had its own version of this in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth were forced from their homes and into state care. The impacts of this cultural degradation were so great that Australians now refer to these people as “The Stolen Generations.”

This attempted erasure of Indigenous culture had devastating impacts on the languages of Indigenous people. Years of children being away from home and assimilated into the state’s culture created a chasm between native communities’ elders and everyone younger than them. Cultural traditions and practices were left in a sort of limbo, with no one to be passed down to. Even more so, languages could only reside on the tongues of older peoples who began passing away. Meanwhile, children away from home not only lost their ability to learn their native language, but they were also conditioned to not speak it at all, facing physical harm if they attempted to do so.

While these ideas may seem archaic, it wasn’t until the late 1960s that all American “Indian Boarding Schools” shut down. The Australian Stolen Generations remained stolen until the 70s, and only in 1996 did the last Canadian residential school close.

A Generational Gap

Though it’s only Australia that technically refers to the lost native people as a “Stolen Generation,” the term pertains to all indigenous children residing in similar schools or institutions. The impact of the people being “stolen,” however, runs far deeper than the obvious trauma inflicted on those directly in the system.

Most of the children who were subjected to the horrors of these institutions are now considered the elders of their respective native communities, and while they all desire to know their native language, many are struggling to do so. With very few indigenous people left who can fluently speak their respective tongues, it puts the existence of all native languages in a precarious position.

On the other end of the spectrum, younger generations are facing the negative effects of social media and an increasingly globalized world. With life rapidly being transferred online, almost everything is in mainstream languages, such as English, the most popular language on the internet. Avoidance of popular languages is unattainable, but the true issue stems from peoples’ beliefs that learning their mother tongue is unnecessary.

For example, in Australia there have long been debates over whether or not Aboriginal schools should be bilingual, or solely taught in English. Similarly, many find that Native languages are useless in the workplace, and therefore unnecessary to know. Most importantly, however, is that most of this is external pressure by governments or corporations in order to retain English as the sole language in the U.S.

Much of the pushback against Indigenous language, while from the outside, has widespread effects on the people at the heart of Native communities, further unrooting and isolating Native people from each other.

A World Without Indigenous Language

Language loss is the lifeblood of Native communities all around the world, intertwined with the wellbeing of its people. Not only does it hold important cultural information, with knowledge of various rituals and customs, but it also helps to shape an Indigenous identity. And when this identity is threatened, so are the people it belongs to.

Things like self-esteem and empowerment are vital to the healing process of Indigenous communities from colonial persecution. Studies from The Lancent Psychology have shown that especially in youth, deprivation of language is linked with mental health issues, including being 50% more likely to have suicidal ideation than those with a greater understanding of their language. Due to the fact that language suppression induces self-esteem and wellbeing issues, many Indigenous communities begin to feel weakened and unempowered, reflecting on their members.

Language loss and suppression is more than just an abstract issue, as with it also comes loss of life. And as loss of Native languages across the world only continues to spread, it prolongs the long, winding road to recovery.

Protecting Indigenous Language

All hope is not yet lost for indigenous languages across the globe. Many initiatives are currently vying for the revitalization of a Native identity, creating classes to learn Indigenous languages and archives and dictionaries in order to preserve what is left of endangered languages. For example, ELA Alliance, a non-profit, is working across the world to retain knowledge of languages in places as remote as Tibetan villages. Other organizations have more specific goals, such as Blackfoot Language Resources, that specifically focuses on creating a database of the Blackfoot language native to areas in America in Canada. Specifically targeting young Indigenous people to learn languages and older Indigenous people to share their knowledge, they strive to not only restore languages, but to also reconnect Native communities.

While these organizations can’t do everything, they are a step in the right direction to help support Indigenous communities. Undoing the damaging effects of colonial structure, they are an act of defiance. Counteracting the cultural submission forced by various reeducation systems, restrengthening Indigenous languages stops these colonial-minded thinkers from achieving their goal, the elimination of a native culture so many years later, and creates a world in which Native communities have a strong voice.

Language loss and suppression is more than just an abstract issue, as with it also comes loss of life. And as loss of Native languages across the world only continues to spread, it prolongs the long, winding road to recovery.