It’s a quiet morning. The birds trill, scrounging for their next meal. The grinding sound of a motor breaks the serenity, and the British prime minister’s car rolls through.

The princess takes a deep breath, holding her banner up.

And she throws herself on the road.

In the mid nineteenth century, India was divided into several empires, each becoming increasingly aware of the intrusive force of the British East India Company. The Company had been annexing sections of India for decades, and was close to gaining total economic control of the subcontinent.

In Punjab, India, war was swiftly approaching. Punjab was part of the Sikh Empire, ruled by the child Maharajah (Emperor) Duleep Singh and advisors to the throne. Duleep Singh had ruled since his father, the renowned “Lion of Punjab” Ranjit Singh, passed away. The Sikh Empire was one of the few sections of India not completely taken over by the Company, but it wasn’t long before conflict broke out.

The Anglo-Sikh Wars, in which the British Empire fought against the Sikh Empire, began in 1848 and lasted a year. After many casualties, the Sikh Empire laid down their arms. The British Army’s victory in the wars led to the annexation of Punjab, the North-West Territories of India, and Kashmir, along with the British possession of the famed Koh-i-Noor diamond.

The eleven-year-old Maharajah was lost. He had been forced to give up his land and now he had nowhere to go. The British East India Company exiled him southeast to modern day Uttar Pradesh, India, where he lived under the guardianship of British army surgeon John Login and his wife Lena. He met Queen Victoria, impressing her enough that she recalled him in her diary as “extremely handsome, speaks English perfectly, and has a pretty, graceful and dignified manner.”

When he was in India, Singh met Bamba Müller, the daughter of a German banker and an Ethiopian woman. The couple fell in love and married in 1864, and the Singh family moved to Britain as the Maharajah and Maharani of Punjab. It was here that they had seven children, five of whom survived infancy.

Two of those children were Princess Catherine Hilda Duleep Singh and Princess Sophia Jindan Alexandrovna Duleep Singh, the latter of whom was the goddaughter of Queen Victoria and the last princesses of the Sikh Empire.

Sophia, Catherine, and their two other siblings, Frederick and Bamba Singh, spent their early childhood in their country estate at Elveden, Britain. Their estate provided them with pastimes generally offered to British aristocracy, including riding and shooting. Meanwhile, Duleep Singh grew restless in England, feeling increasingly out of place. He secretly joined resistance against British Imperialism in India, hoping to one day free the country.

But when Catherine was 16 and Sophia was 11, their life of comfort began to quickly fall apart. Their parents’ marriage was in shambles after Duleep Singh was exiled to France after he was exposed for attempts to try to take the Sikh Empire back from the British. He eventually died after six years in exile.

Bamba Müller Singh contracted typhoid and passed away soon after, leaving the Singh children without a guardian until Queen Victoria stepped in. The Queen took responsibility for the children, sending them to live with British guardians Arthur Oliphant and his wife with an annual allowance from the Indian Office. It was here that they were introduced to their governess, Lina Schäfer.

Schäfer was 27, 12 years older than Catherine at the time, but they quickly became inseparable friends. Eventually, they would fall in love, and Schäfer and the Princess would remain romantic partners for as long as they lived.

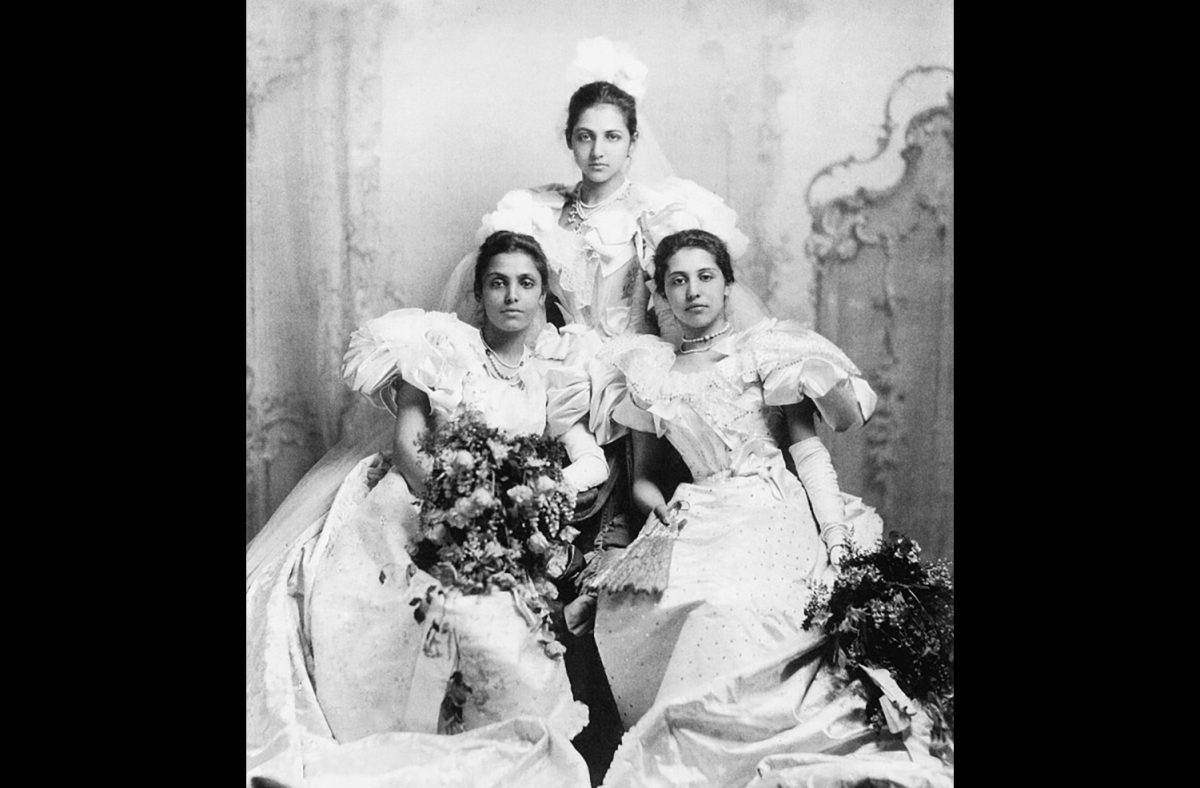

The Singh daughters were presented as debutantes in Buckingham Palace in 1894, wearing fine white silk and tulle in their all-too-famous photograph. In it, Catherine stands in the middle, her eyes peering upwards, fixing the watcher in place. Her regality is unmistakable, and her sisters are no different; Sophia is on the left of the photograph, next to her older sister Bamba, and she pierces the camera, leaning backwards as if in approval. The princesses are in their early 20s and late teens, and the regality radiating from the photograph is unmistakable. The Queen formally proclaimed them as princesses in 1896.

And so, the years passed. Since Sophia was Queen Victoria’s goddaughter, she tended to receive more of the monarch’s affection than her siblings. She was given a grace-and-favor apartment from Victoria when she reached 18 that she would use for the rest of her life. “From an early age, [Sophia] learned to negotiate between the easy existence granted to her as a member of Britain’s elite and her ambiguous position as an Indian woman living in Britain during the heyday of the British Empire,” historian Elizabeth Baker writes in the book The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign.

Meanwhile, Catherine attended Somerville College, Oxford where she studied French and German and received private instruction in violin, singing and swimming. Women were not given degrees at the time, so Catherine did not formally receive any title for her education, but her education in the languages helped her communicate better with Schäfer, who was German.

Both girls never forgot their Indian heritage, and embarked on a clandestine voyage to view India in 1903 visiting Lahor, Kashmir, Dalhousie, Simla, and the holy Sikh city of Amritsar. This opened both sisters’ eyes to the toll that British colonialism had taken on their ancestry, making it difficult for them to ever view the monarchy the same way again. It was here that Sophia became acquainted with many Indian women’s suffragists, avid voices of the cause. Anita Anand, author of Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary, later said the trip, “brought her alive and turned her into a revolutionary.”

Britain and women’s suffrage share a tumultuous history, of which the princesses were avid witnesses to as they grew up. Much like other countries around the world, suffrage had been seen as a right exclusively given to men for centuries. The idea that women were intellectual equals seemed absurd.

So while Sophia and Catherine grew, Britain struggled within itself. Prominent British suffragettes fought as the world grew increasingly aware of their cause. It was alluring to so many women and people around the world.

It drew the princesses in.

As the sisters entered adulthood, they found themselves in a world teeming with revolution. Europe was fraught with tension that would later spark the first World War. Sophia joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) shortly after meeting one of the society’s members, Una Dugdale, in 1908. She also joined the Women’s Tax Resistance League, where she would take part in protests that involved refusing to pay taxes. As Anita Anand said, “Though courts demanded it, she refused to pay, embarrassing King George V who cried out, ‘Have we no hold on her?’”

Meanwhile in 1908, Catherine and Lina looked for places to settle. They decided on Kassel, Germany, where Lina was from, and lived peacefully. In their private accounts, Catherine wrote, “I am having a very good time of it and enjoying myself thoroughly” while Lina wrote, “We are like two mice living in a little house.”

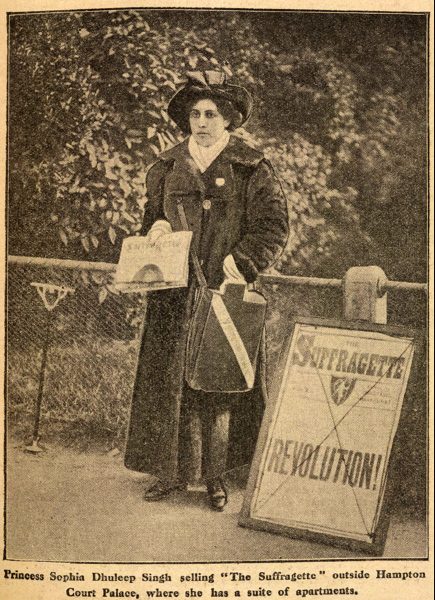

In 1910, Sophia was one of 300 delegate suffragists who marched to the London Parliament, seeking an audience with then Prime Minister HH Asquith, on a day later known as Black Friday due to the brutality that the protestors faced. 115 women and four men were arrested, with Sophia included. Often, Sophia would use her home bestowed upon her by Queen Victoria to organize suffragette protests and meetings. She would often sell the pro-women’s suffrage newspaper, The Suffragette, in front of her home. In 1911, Sophia was the princess who threw herself at the British Prime Minister’s car with a banner proclaiming, “Give women the vote!” in hand. She emerged relatively unscathed, but it demonstrated how dedicated she was to the cause.

That wasn’t to say that Catherine wasn’t involved with the suffragist movement back in Britain like her sister. While living in Germany, she was an active member of the Fawcett Women’s Suffrage Group and the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, though it is unclear when she joined each organization. In 1912, in an effort to raise funds for the “constitutional women’s suffrage works” she established a forest of Christmas trees in Birmingham, with all funds going towards the cause.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 threatened the lives both sisters had built. Catherine chose to remain in Germany with her partner Lina, despite the risk of being called a traitor. Meanwhile, Sophia joined a 10,000-woman protest march against the prohibition of a volunteer female force, and volunteered as a British Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse from October 1915 to January 1917 at the Isleworth Aux Military Hospital. She also tended to wounded Indian soldiers, many of whom were shocked that the granddaughter of the famous Ranjit Singh sat by their bedsides.

The hard work of the suffragettes in Britain finally began to pay off soon after the end of WWI. In 1918, the “Representation of the People Act” was passed, which allowed women over the age of 30 to vote. It was a win, even if there was a lot more work to be done.

Both sisters kept a relatively low profile in the following years, but still fought for women’s rights. The Equal Franchise Act was passed in 1921, which allowed women over 21 to vote on par with men. The work that the suffragettes had tirelessly done for years had finally paid off. In 1934, Sophia appeared on an edition of the British Magazine Who’s Who, citing her life’s purpose as “the advancement of women.”

In the mid 1930s, on the brink of WWII, Catherine watched the Nazis’ oppression firsthand in Germany. The neighbors of Catherine and Lina reportedly said, “The local Nazis disapproved of the old Indian lady.” The couple worked towards helping as many Jewish families as they could escape, earning Catherine the affectionate nickname “Indian Schindler.” One family they saved was the Hornstein family, which consisted of Wilhelm, Ilse, Klaus-George and Ursula Hornstein. In 2003, Ursula reflected on Catherine, saying that she was, “A perfect stranger to do that… what you might call a good Samaritan.” Lina died in 1938 at 79 years old, leaving Catherine heartbroken in an increasingly dangerous Germany. At the advice of her aide, she evacuated Germany to move back to London the same year.

Perhaps it was for the best that Catherine evacuated when she had – WWII began the following year.

Sophia and Catherine remained close. They were the only two of their remaining siblings in Europe as WWII raged on and fell into a comfortable balance together as they entered their late sixties and seventies.

On November 8, 1942, the siblings attended a drama at Penn, a village in Buckinghamshire, England, dined, and retired for the night in Catherine’s home in the village.

The next morning, the maid attending Princess Catherine’s room found her door locked. She informed Sophia, who broke down the door to find that Catherine had passed away due to a heart attack. She was 71.

Sophia was inconsolable at her sister’s death and was the only relative to attend her cremation because of the travel restrictions during WWII. Following Catherine’s death, Sophia became the owner of her home in Penn. Sophia renamed the Colenatch House, where the sisters had last dined, to “Hilden Hall” after Catherine’s middle name and sealed the room where Catherine had passed.

She resided there during the years following Catherine’s death, retiring from most of her involvement in the women’s rights movement in her last years. Princess Sophia lived long enough to witness India’s independence and the Partition, where the land that had formerly belonged to her family was split between two countries – Pakistan and India. As Anand wrote, “Sophia lived to see the British leave, and mourned what had been left in their wake.”

On August 22, 1948, Sophia died in her sleep in the same estate as her sister at 72 years old.

Sophia’s contributions to the women’s rights movement were not forgotten. Sophia and 58 other women’s suffragists have been featured on a plinth of Millicent Fawecett, installed in 2018 in Parliament Square, London. She was featured in the documentaries Sophia: Suffragette Princess (2015) and No Man Shall Protect Us: The Hidden History of the Suffragette Bodyguards (2018).

In January 2023, it was announced that a blue plaque would be installed on the home Queen Victoria granted Princess Sophia and her sisters, commemorating Sophia’s fearless help to the suffragette cause. On May 23, 2023, it was announced that a movie titled Lioness that would focus on Sophia was in the works, with Paige Sandhu set to represent the princess.

Princess Catherine’s name made its way into mainstream media one more last time in July 1997, when a dormant joint account under her name and Lina’s was discovered in Swiss banks. Though it was initially reported as a novel new lens into British oppression of India, it became clear that the extra account simply contained funds Catherine had set aside, perhaps for some of the Jewish families she had assisted with escaping.

There are no living descendants of the family, as none of the children of Duleep Singh had children. Not many people had even known of the princesses and all they fought for until the aforementioned surge of content related to Sophia.

But it cannot be denied that the princesses were extraordinary. They lived and they fought, each in their own way. The brilliance of their story nearly seems like fantasy, yet it would be a disservice to both sisters to simply tout it as that. Sophia and Catherine were real people, whose legacies should not be forgotten. When Anand wrote about Sophia, she said, “Because of women like her, I have a say in who governs my future. It became my duty to tell her story and put her back in her rightful place in history.”

Maybe you don’t need to throw yourself at a car to be a hero, or save multiple families from certain death. Yet that was what the princesses did.

And perhaps that is enough.

When Anand wrote about Sophia, she said, “Because of women like her, I have a say in who governs my future. It became my duty to tell her story and put her back in her rightful place in history.”