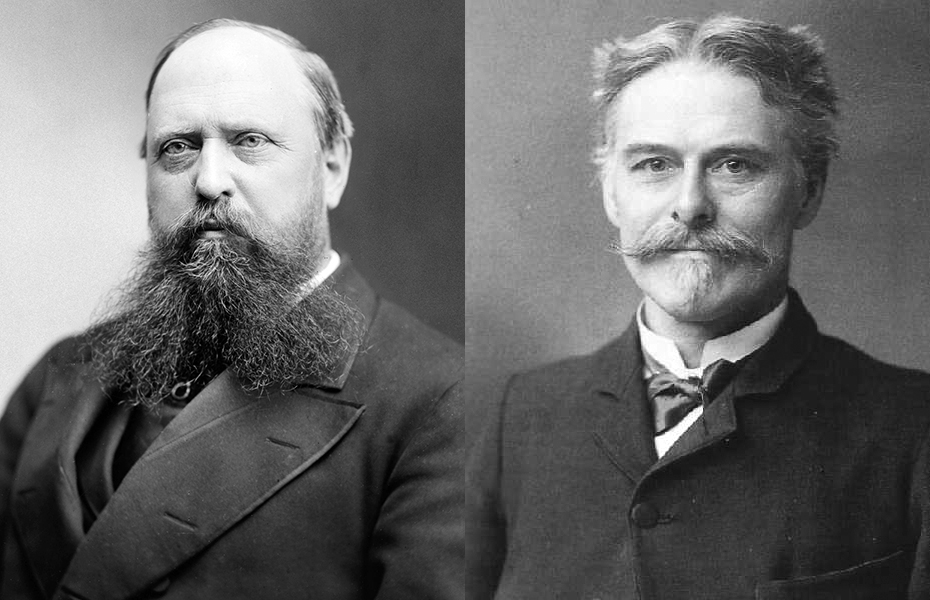

Unless you live 100 feet under the largest rock on planet Earth, you’ve heard of dinosaurs. You’re probably familiar with the Triceratops and the Stegosaurus, and if you’re a dinosaur fanatic, the Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and other famous species like the Coelophysis. What you likely don’t know, however, is the bitter rivalry that led to these iconic species’ discoveries. Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope were two scientists who shared similar passions and extraordinary talent for paleontology. Their common interest is what led them to an intense rivalry that lasted nearly two decades: The Bone Wars.

Before the Meeting

Marsh and Cope met in 1864. In the beginning, they were amicable, though they had different upbringings. Cope was born to wealthy Quaker parents in Philadelphia, while Marsh was born into a poor family in Lockport, New York.

Cope grew up with the privilege of extensive education. His parents felt strongly about raising their children to be intellectuals, and early on in his life, Cope was taught to read and write. His parents often took him to various museums and zoos, where he quickly discovered his interest in animals, which later fostered his passion for paleontology.

Cope was sent to expensive private schools his entire life. He excelled in academics, but it was discovered early on that he had issues with loneliness, and bad conduct. He had a difficult temper, which was noted by his teachers at private school, and persisted throughout his years at the Academy of Natural Sciences. Despite his behavioral issues, Cope still excelled in his field. He worked as a researcher at the academy and published his first scholarly article at the age of eighteen. However, Cope’s father had a different life in mind for him. He wanted his son to be a farmer, but despite their opposing views, he supported Cope financially when he left to study paleontology at the University of Pennsylvania. To avoid the Civil War draft in 1863, Cope’s father sent him to Germany to study natural history.

Marsh had a vastly different life leading up to his meeting with Cope. His family struggled financially throughout his childhood following the passing of his mother when he was just three years old. Similarly to Cope, Marsh’s father expected him to pursue a life as a worker on their family’s farm, but Marsh had other aspirations. He discovered his love for science at an early age, and with the financial help of his uncle, George Peabody, Marsh was able to leave his family’s farm and attend university. He attended Phillips Academy, then after his first year, he transferred to Yale University. After excelling at Yale, he moved to Germany for graduate school. It was there that he met Edward Drinker Cope.

Amicable Beginnings

The pair met in 1864 and became friends quickly. They spent several days touring Europe together before they both returned to the United States. Cope and Marsh were both getting into the world of discovering new species of fossils. Their pursuit coincided with America’s newly accelerating westward expansion and new railroads, and the two capitalized off all the new land they could scour for new species of fossils. The two remained friends upon their return to the U.S., even going as far as to name species they discovered after each other. Cope named the Ptyonis marshii after Marsh, and Marsh named the Mosasaurus copeanus after Cope. Both Cope and Marsh were achieving high levels of success in their fields. However, Marsh made a decision that consequently ended his friendship with Cope.

In 1868, in the spirit of sharing findings with someone he thought was his intellectual companion, Cope had brought Marsh to a fossil quarry in Haddonfield. Marsh took advantage of this. Without Cope’s knowledge, he spoke with the quarry’s owner and made an arrangement that would have all new fossils discovered in the quarry sent to him, so he would have first access to as many new species he could publish under his name. Marsh wasn’t finished there, however. Later that year, Cope published his research on a new species he discovered, a type of platyurus, but made an error in his reconstruction of the fossil. Marsh was the first person to publicly point out Cope’s mistake.

“When I informed Professor Cope of it, his wounded vanity received a shock from which it has never recovered, and he has since been my bitter enemy,” Marsh reflected on the event.

Marsh and his team at Yale University began scrambling west to dig for fossils, Cope following shortly after. Marsh and Cope were both finding new species at a rate never seen before. However, with the rapid pace at which they were putting together and naming these species, their reconstructions were prone to errors. Marsh and Cope often named species they believed were new but, in reality, were not. When they each published their findings, the other would race to expose mistakes. They often argue in scientific journals, going so far that The Naturalist had to ban them from criticizing each other.

Marsh was the one to escalate the feud once again. He was determined to take out Cope. Marsh secured a position as the chief paleontologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, an official agency of the U.S government. Marsh used this power to bar Cope’s access to federal funding and grants for his fossil excavations and research. In the end, Cope couldn’t secure the finances on his own to continue. He dropped out of the “race” with Marsh.

Marsh still hadn’t had enough. In 1890, Cope had little left. He and his wife divorced and he retired from rapidly exploring the west for new fossils. What he still did have, however, was his collection of fossils, but Marsh couldn’t let him keep that. He claimed that because the federal government previously funded Cope, his fossils belonged to the country, not him. Cope wouldn’t accept this.

Cope gave information to a journalist for the New York Herald about Marsh and his team’s misuse of funding and overwhelmingly corrupt behavior during his fossil expeditions. In response, the government fired Marsh from his position and took the majority of his fortune.

Their feud ruined their reputations irreparably. They both died young, Cope at age 56 and Marsh at age 67, and with little money or belongings to their names. Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope had successfully destroyed each other.

It wasn’t all bad!

Though Marsh and Cope left behind tarnished images for themselves, they also left behind massive discoveries. Combined, the two of them discovered over 25,000 new fossils. Of the 3,200 vertebrate fossil species, Cope described 1,115, and Marsh described 496.

The two discovered many of the most recognizable species of dinosaurs known today, including the Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops, and many more.

Although Marsh and Cope had a bitter feud, they drove each other to incredible intellectual success. Like the fossils they discovered, the change they made in the world of paleontology, will stand the test of time.