“I like living. I have sometimes been wildly, despairingly, acutely miserable, racked with sorrow; but through it all I still know quite certainly that just to be alive is a grand thing.”

Perhaps it’s counterintuitive to have the most well-known murder mystery writer hold life in such a regard. After all, most of her books start off with death. Yet, it is through death that Agatha Christie’s view on life shines and the complex writer behind the orchestrated mystery reveals herself.

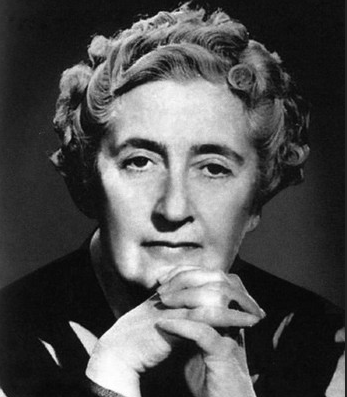

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie was born on September 15th, 1890, in Torquay, a small seaside town in England. Her parents, Frederick Miller and Clarisa Boehmer, were both wealthy socialites. Christie spent most of her childhood running along the coastlines and making up stories and characters in her head.

Despite her mother’s wish for her to not read books until she was older, Christie taught herself how to read early on, falling in love with books by Edith Nesbit, Mrs. Molesworth, and, later, Lewis Carroll. Christie would later recall in her memoir that since she was homeschooled, she didn’t have the opportunity to make many friends her age. The books she read became her constant companions, nurturing her avid imagination.

When Christie was eleven years old, her ailing father died after a battle with chronic kidney disease and pneumonia. The Miller family was thrust into turmoil, leaving Christie’s mother no choice but to enroll her in primary school. The rigid structure of Torquay’s public schools in comparison to her previous homeschooling came as a shock to Christie, and at sixteen, she was sent to Paris to finish her education in boarding and finishing school. It was in Paris that Christie cemented her love of the arts and literature through visits to many of the city’s famous museums and literary spots. Later, Christie would write many novels set in France, inspired by her time spent in the country.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before her mother’s health began to fail as well. In hopes of warmer weather curing her, Christie decided to move with her mother to Cairo, Egypt in 1910. Cairo helped Christie fall in love with the archeological discoveries and history of Egypt – themes that would later feature heavily in her books.

After a few years in the warm climate, Christie and her mother returned to England, World War I on their heels. It was in this tense environment that Christie wrote her first novel, Snow Upon The Desert. Although Snow was rejected by almost all of the publishers she sent it to, one saw promise in her and encouraged her to write a new novel.

Around the same time in 1914, Agatha attended a dance, where she caught the eye of an army officer, a man thirteen years her senior named Archbald “Archie” Christie. The two quickly fell in love, getting engaged only a few months afterwards. When World War I broke out, Archie was drafted, so the Christies wound up getting married on Christmas Eve of the same year when he returned for a leave.

While Archie served in France, Agatha Christie worked as a nurse and a dispenser for over 3,400 hours in the Red Cross Hospital of Torquay while drafting her first mystery novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in 1916. In order to work as a dispenser, Christie had to take the Apothecaries Hall examination, one that required intense studying of chemistry and pharmacy. She grew incredibly well-versed in poisons, a quite prominent (and scientifically accurate) plot device in Styles.

Fortunately for the Christies, Archie survived his service, and once the war had ended began to work in London’s financial world. Agatha left her job at the Red Cross, and the couple welcomed their child Rosalind Margaret Clarissa Christie in August 1919. But she had not given up on the literary world just yet – since her initial draft of The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Christie had been working tirelessly to get it published, despite the rejections that consistently came in. Four years after she had set pen to paper, a publishing company offered to publish Styles if she changed the ending.

She accepted.

For the next few years, Christie kept writing and publishing novels and short stories – many of which featured Hercules Poirot. Today, Poirot is considered one of her most famous characters; he is a Belgian detective, with an ego that Christie herself called “insufferable,” who appeared in 33 novels, two plays, and 51 short stories. The invention of Poirot in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, along with the incredible quality of her work, set the stage for Christie’s budding success.

Yet as her writing career blossomed, her marriage began deteriorating.

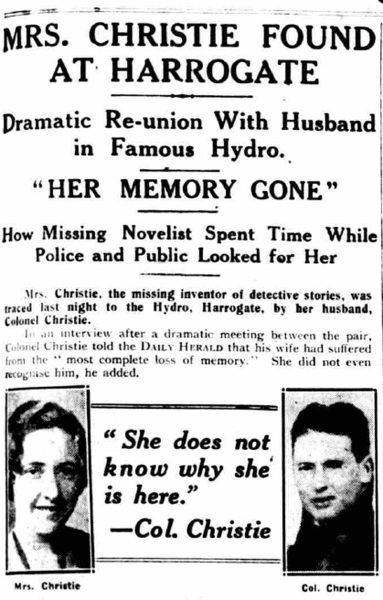

In 1926, Christie’s mother passed away. Around the same time, Archie told Agatha that he had fallen in love with another woman and asked for a divorce. After a heated argument on the eve of December 3rd, Agatha Christie calmly wore her coat, kissed her daughter on her forehead, and disappeared into the night.

The disappearance of Agatha Christie was a strange one, akin to the plot of her bestselling books. At the time of her disappearance, Christie was a fast-rising celebrity – only adding to the media attention. Hundreds of police officers scoured the streets for days, finding only her abandoned car with clothing, scattered papers, and no sign of the author.

Eleven days after her disappearance, Agatha Christie was finally found at a hotel in Harrogate, checked in under the fake name Teresa Neele. She claimed to have come from South Africa, and when returned, stated that she had lost all memory of her disappearance. “You can’t write your fate,” Christie would say, years later, “but you can do what you like with the characters you create.”

To this day, it is unclear if Christie’s disappearance was a publicity stunt, revenge on her husband, or something entirely different. In her own autobiography, Christie spares it barely a page, still claiming amnesia. Yet if there was one thing that it accomplished, it cemented something already well known: Agatha Christie was a force to be reckoned with.

The Christies finalized their divorce in 1928, and Agatha was given sole custody of their daughter. She kept publishing short stories, plays, and novels at a breakneck pace, shooting up in the publishing ranks until she became – and remains – the bestselling author of all time.

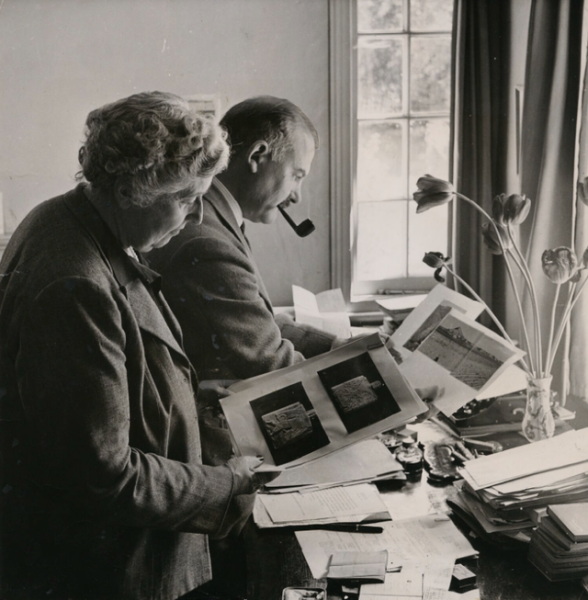

Her years in Cairo, and the love for archeology and history they sparked, never truly left her, and it was because of that that she went on a visit to Ur, Iraq in 1930. There, she met Max Mallowan, an archeologist fourteen years her junior working on the dig site she passed through. They quickly fell in love, and married just six months after their initial meeting. They would stay married until Christie’s death.

The 1930s were eventful for Agatha Christie. World War II was approaching quickly as Europe fell into tumult, and it was around this time that she released some of her most famous books, including Murder on the Orient Express (1934), Death on the Nile (1937), and And Then There Were None (1939). Meanwhile, her stature in the literary world led her to feel slightly trapped; she wanted to explore different genres, yet it was almost as if she had become a brand.

It was these years that Mary Westmacott, Agatha Christie’s alternate identity, was born. Westmacott gave Christie the freedom to explore semi-autobiographical novels, centered around love and coming-of-age. Rosalind would later say, “The Mary Westmacott books have been described as romantic novels, but I don’t think that is really a fair assessment. They are not ‘love stories’ in the general sense of the term, and they certainly have no happy endings. They are, I believe, about love in some of its most powerful and destructive forms.” Christie would go on to publish six novels as Westmacott until the 1950s.

As the 30s concluded and And Then There Were None was published, World War II broke out, and Christie and her family moved to London.

In London, she rejoined a pharmacy as the war raged on. Her initial knowledge of poisons, collected during the first World War, only grew. Christie had grown to be so well-versed in poisons that she would be considered a “poison master” for much of her later life. This job inspired her later novel, The Pale Horse, a book that would solve a thallium poisoning case in 1977, as British medical personnel had read the novel and recognized the symptoms.

The war ended in 1945, yet the grief that permeated most of the world had not. It was prominent in Christie’s work as well; The Hollow, a murder mystery, features firearms throughout the story and discussions on the fleeting nature of life.

Post-war, Agatha Christie continued to write prolifically, honing a skill that still earns her critical acclaim to this day. As Eleni Skasilas ’24 said, “She is really good at putting the reader in the same boat as the characters. We are able to try and solve the mystery with the characters, but end up just as confused till the ending.” She became an international celebrity in the literary world, earning around ₤100,000 annually by the 1950s (around $5.5 million today.) She wrote her final two novels as Mary Westmacott in the 1950s (A Daughter’s A Daughter and The Burden), ending a chapter of her life and markedly moving on to her next one. This new era led to her experimenting with more mediums, including playwriting. The Mousetrap, the longest running play in history, debuted in 1952 in London’s West End and has been playing ever since. It famously includes a twist ending that audiences are still asked not to reveal when they leave the theater, a testament to her enduring genius.

In 1956, Christie was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and in 1961, she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Literature degree by the University of Exeter. She created The Agatha Christie Trust for Children in 1969, a charitable organization aimed at helping the elderly and young children. As she entered her 70s, Agatha Christie began writing through recording herself speaking the prose out loud for it to be later transcribed, as committed to her craft as she had ever been. This commitment was recognized as she was promoted to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II in 1971, officially making her Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie.

Agatha Christie died peacefully on January 12th, 1976, at age 85. She had published 75 novels under her name, including collections of short stories, and had sold over two billion copies of her books – outsold only by The Bible. Her legacy was, and still remains, a testament to her literary genius.

In her novel The ABC Murders, Christie wrote “Words, mademoiselle, are only the outer clothing of ideas.” And truly, that is what her impact on the world comes down to. Agatha Christie will forever be remembered as the “Queen of Mystery” because of her ideas and the worlds she created with them, a title enduring even to today.

When asked about the most unique aspect of Christie’s writing, Jaime Yu ’25 said, “The most unique part about Agatha Christie’s writing is her creativity in writing mystery books, to use different styles and strategies in writing to cleverly lay out clues for the reader and the detective of the book, Hercules Poirot or Ms. Marple, to piece together and form a solid replaying of the crime or mystery in play.”

Christie’s impact on both the literary industry and the world as a whole remains prominent, even almost fifty years after her death.

The little girl from Torquay’s shores who made up stories in her head certainly did not lead a boring life. And neither did the starry-eyed teenager in Paris, nor the brand-new author falling in love with poisons and archeology. Agatha Christie was a force to be reckoned with, and still remains as one so many years later.

After all, the best mysteries begin with a mastermind.

As Eleni Skasilas ’24 said, “She is really good at putting the reader in the same boat as the characters. We are able to try and solve the mystery with the characters, but end up just as confused till the ending.”