“What is the Absolute? Something that appears to us in fleeting experiences – say, through the gentle smile of a beautiful woman, or even through the warm caring smile of a person who may otherwise seem ugly and rude. In such miraculous but extremely fragile moments, another dimension transpires through our reality. As such, the Absolute is easily corroded; it slips all too easily through our fingers and must be handled as carefully as a butterfly,” wrote Slavoj Žižek in his book The Fragile Absolute: Or, Why is the Christian Legacy Worth Fighting For?

Over the last 30 years, Slavoj Žižek has cemented himself as a highly distinguished figure in psychoanalysis, expressing his views regarding love, life, and government across nearly the entire media landscape, including movies, books, published articles, and YouTube videos.

The result is a hyper-fascination with Slavoj Žižek. Accelerated by social media, his doctrine, once followed by only niche communities, has spread to much more mainstream culture.

To explain the internet’s newfound captivation with Žižek, and his perspectives regarding modern life, we must first explore his origins as a cultural theorist and worldwide intellectual.

Slavoj Žižek was born in Ljubljana, Slovenia, formerly the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, a Communist state. From a young age, he was captivated by Western culture and media, fueling his early ambitions to pursue a career in film. While he redirected himself towards a profession in philosophy, his love for the art of cinema would later intertwine with his career as a psychoanalyst.

Before attending the University of Ljubljana, where he graduated with a Doctor of Arts in Philosophy in 1981, Žižek served his mandatory year-long national service in Karlovac’s Yugoslav People’s Army.

Žižek has often expressed his indifference to the former nation, occasionally using his platform to express his lack of “Yugo-nostalgia,” or nostalgia for Yugoslavia before its dissolution in 1991. This has made him somewhat of a contentious figure among Eastern European leftists, many of whom reflect on communist Yugoslavia with rose-tinted glasses.

Interestingly, he was indifferent to Slovenia’s declaration of independence from Yugoslavia, stating that he “didn’t care about it” at the time. When discussing modern-day Slovenia, he has argued that the nation has failed to fulfill its potential as an independent democracy.

Despite his detachment from the fight for Slovenian independence, Žižek was politically involved during the movement. For two years, Žižek distinguished himself through his activity in social movements which called for the democratization of Slovenia.

These movements arose almost immediately after the nation’s inception, as the transition from a one-party socialist system to a multi-party democracy expanded the political landscape. In 1990, Žižek was a strong candidate for the presidency of the Republic of Slovenia in the country’s first-ever democratic election.

Due to the political divisions that took root in Slovenia, as well as the potential compromise of his cultural and societal beliefs, Žižek abandoned his political aspirations. Fortunately, he maintained a strong international presence in the philosophical community.

Žižek himself is a communist; however, his refusal to possess “Yugo-nostalgia” indicates how his more practical vision of communism differs radically from previous implementations of the controversial political system.

Instead, he focuses on exploring Marxism in contemporary society and the different ways in which capitalism has accentuated class struggles and social injustice. He also critiques ideological structures on both sides of the political spectrum, encouraging others to do the same.

By the early 2000s, Žižek’s unique voice and ability to simplify complex social phenomena made him relatively popular in expanding communities of modern political philosophy. With most modern-day theorists, their ideas, while important, are often overcomplicated by intellectual jargon and political buzzwords. They would rather appeal to the “intellectuals” sitting in their circle instead of concisely explaining their beliefs to the masses.

These philosophers would be better suited to pursue careers as politicians instead of social theorists, as politicians have no problem with forcefully trying to sound smarter than the people they are meant to appeal to.

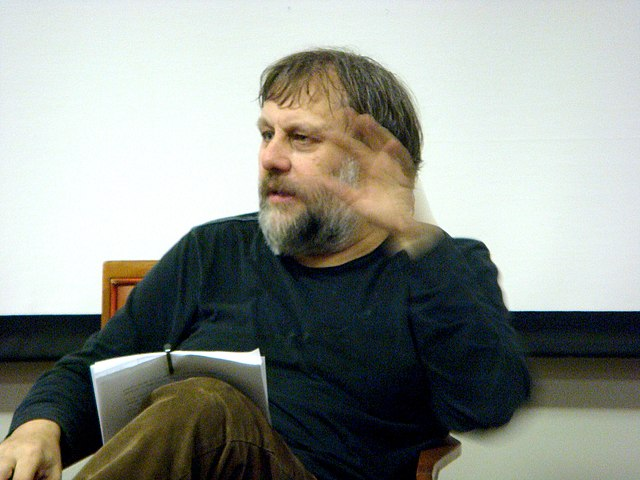

Žižek, on the other hand, is always engaging, speaking with a contagious excitement that captures the attention of anyone willing to listen. He’s animated and lively in his speech, giving the impression that instead of simply explaining ideas to his audience, he disperses them in a passionate and fanatical display of wisdom. His nervous ticks composed of constant sniffling and shirt pulling only add to the enthralling chaos that ensues whenever it’s time for him to speak his mind.

This is the defining difference between Slavoj Žižek and most other public intellectuals. To put it simply, he makes philosophy “cool” by presenting it in a way that anyone can understand and engage with. They don’t need to be well-versed in Marxist theory to feel the significance of what Žižek has to say about modern, capitalist society.

Žižek’s philosophies can be labeled as “left-leaning” or “anti-capitalist.” However, his general stance on societal issues and government systems cannot be so easily classified under oversimplified terms like “liberal” or “conservative,” as is the case with most modern-day cultural/political theorists.

You may have heard of Žižek or seen clips of his speeches online because, unlike most contemporary psychoanalysts, he maintains an incredibly strong presence across all facets of media. This includes his aforementioned publications, video interviews, news articles, and full-length feature films, which express his approaches to cultural theory in ways that make them much more accessible.

Instead of consulting lengthy lectures and dissertations in the search for Žižek’s perspective regarding a certain issue of importance, a vast majority of his outlook on pressing societal matters lies in these easily available digital mediums. This makes it so that anyone who might stumble across a snippet of his passionate dialogue can quickly sink into the Žižek rabbit hole.

The puzzle of Žižek’s pop-culture presence would be incomplete without the discussion of his ventures in the world of modern cinema. While he’s featured in many independent films and documentaries as a lecturer or interviewee, there are three particular projects that encapsulate his efforts to blur the line between cultural theory and movie magic.

Žižek on the Big Screen

Žižek!

In 2005, ‘Žižek!’ a documentary directed by Astra Taylor was released. The documentary revolves around Slavoj Žižek’s life and his significance in the world of psychoanalysis and modern-day philosophy. The film also explores Žižek on a more personal level, with scenes of him explaining his anxiety before an important event and the interesting curation of his home in Slovenia. We also see him traveling from location to location, the film crew giving us a glimpse of his personality and perspectives on the smallest matters.

My personal favorite scene is of him perusing a video store in New York City, frantically asking for film titles that are far too specific, and then abruptly transitioning to him discussing what he believes to be the best movies of all time. Their time in the video store ends with the documentary director, Astra Taylor, paying for the movies he was so excited about.

The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema

The 2006 film, ‘The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema,’ was the first clear instance of Žižek’s admiration for cinema, perfectly intertwining with the world of psychoanalysis. His ‘Pervert’s Guide’ duology is quite unconventional in the sense that it does not have any particular plot or evolving story. They are instead composed of Žižek using a philosophical context to explore movies and other popularized pieces of media.

He discusses classic films like ‘Vertigo,’ ‘Psycho,’ and ‘The Matrix’ whilst applying psychoanalytic principles, which give us a much deeper understanding of not only these particular films but also human behavior on a fundamental level. He traverses concepts such as the relationship between our perceived reality and our deepest desires and the idea of undying energy, which exists independently of our life and death cycles.

The latter was brilliantly explained using a well-known scene from ‘The Exorcist,’ involving two priests attempting to expel the malevolent spirit controlling a young girl.

The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology

In 2012, Slavoj Žižek released his final self-starring film, ‘The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology.’ Similarly to ‘Pervert’s Guide to Cinema,’ this film combined psychoanalytic elements with Western cinema. This time, however, Žižek focused on the underlying machinations of ideology. As a widely consumed art form, cinema is filled with structures and ideologies that define how we live our lives, often on a completely unseen level.

Žižek best encapsulates this idea with his analysis of John Carpenter’s ‘They Live.’ He asserts that ideology is not simply a set of ideas or principles imposed onto us by authoritative figures, instead it serves as our very perception and relationship with the social world around us.

Žižek expands out of the world of cinema in his final film, also exploring the cycle of capitalistic consumption utilized by enormous brands as well as the philosophical significance of at-the-time current events.

Marxism In Your Pocket

In our new digital world, where information is flying at you faster than you can even perceive it, audiences no longer stumble upon Slavoj Žižek via personal research or the niche communities they are subscribed to.

Instead, it is most often mainstream social media platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook that spread the philosophies of Žižek far and wide. You may stumble upon a short clip of him describing how capitalism has seeped into the deepest recesses of our minds, making it so that an accentuated economic principle has manipulated our ability to desire.

However, how he expresses this idea with his frantic language and hyper-enthusiastic demeanor draws people toward his teachings and his persona. We are lucky that he advocates for radicalized forms of freedom and an escape from our societally imposed constraints, as the power he holds with his massive online presence can easily be misused by those with alternative beliefs.

This strategy of rapid media utilization is used similarly by modern social commentators such as Ben Shapiro and, more closely connected to the world of psychoanalysis, Jordan Peterson, whose ideologies often lie on the opposite end of the political spectrum compared to those of Žižek.

Of course, this oftentimes makes the influence of Peterson and other right-leaning commentators’ ideologies equivalently appealing to the mass public as those of left-wing intellectuals like Slavoj Žižek.

This phenomenon of social media sites prioritizing the exposure of heavily conservative activists on their algorithms has been dubbed the “alt-right pipeline.” For years, it has been a topic of great controversy in the discussion of digital political influence, primarily because it is responsible for the rapid alt-right radicalization of young people on social media and its contribution to the now polarized political environment.

Slavoj Žižek’s cultural theories expand much further away from politics than the topics of discussion that these conservative intellectuals often dwell upon.

While these intellectuals are arguing with college students about gender identity and entertaining the idea of a brewing second civil war, with them being on the side more closely akin to the confederacy, Žižek discusses his views on modern love or the wonderful drive found within ourselves by a creative endeavor.

His ability to expand far outside of the established political echo chambers that seem to plague Western media makes him and his perspectives unique in an entirely different regard. For once, an online influence does not exist solely to entertain the now-exhausted political spectrum. Of course, he still has views on major world issues and topics that define modern culture, but he does not let these ideas define him in any significant way.

As mentioned previously, it’s very difficult to apply labels on Žižek because his views are entirely the product of his experience with psychoanalysis and his perception of life under omnipresent capitalism. One of his perspectives may appear more rightwing, while another undeniably reflects the radical left. He simply refuses to conform to the tiresome Western narratives surrounding political affiliation.

When asked about his views on transgenderism, Slavoj Žižek concluded his answer with a simple assertion: “the greatness of transgenderism, for me, is precisely that it brings us closer to a more radical sense of freedom.”

In our complex and ever-evolving political world, where the words of a socially awkward Slovenian philosopher touch the hearts of many Americans in a more meaningful way than any politician or “true American” public intellectual, we owe it to ourselves to live our lives in the continuous pursuit of a “more radical sense of freedom.”

Whether that entails an uprising against the deeply-rooted late-stage capitalism of our modern world or simply a reevaluation of what we desire from life on an interpersonal level, we must aspire for what will make us radically free.

While these intellectuals are arguing with college students about gender identity and entertaining the idea of a brewing second civil war, with them being on the side more closely akin to the confederacy, Žižek discusses his views on modern love or the wonderful drive found within ourselves by a creative endeavor.