The Comet Ping Pong, located on Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C.’s Chevy Chase neighborhood, boasts a rather hip environment for a joint pizzeria/concert venue. Described as a “haven for weirdos,” it sports an eclectic air, ping pong tables situated in front of brown pews, and live music sessions at night, featuring punk rock bands. Outside the pizzeria is the signature Comet sign, bright yellow in the daylight and lit up orange during the evenings. With a complementary review by The Washington Post and 4.0 rating on Food Network, it seems just like your average, if not a tad bit strange, pizza place.

That is, until December 4th, 2016, when Edgar Maddison Welch walked into the Comet and fired three rounds inside the building.

After his arrest, Welch was found with a total of four weapons in his possession, consisting of a semi-automatic rifle, a handgun, shotgun, and a folding knife. Thankfully, he was arrested before he was able to cause any serious harm. Welch was charged with assault, carrying weapons without a permit, and unlawful discharge of a firearm, earning a sentence of four years in prison. He was released on May 28th, 2020, after being sent to a Community Corrections Center (CCC).

On the day of the shooting, Welch drove from Salisbury, North Carolina to Washington, D.C., carrying with him his weapons and a dangerous plan. But why? What business did Welch have with The Comet Ping Pong? Why had he opened fire inside the establishment, putting dozens of people in harm’s way?

The answer dates back to March 2016, right in the midst of the presidential race. Political tensions had started to climb, with insults being flung between Democrats and Republicans as they battled over who was more fit to run the country. The Democratic and Republican primaries were underway to determine who would run in the general election. Then came something that shook up the American consciousness: the e-mail account of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chair, was hacked.

About 50,000 e-mails related to the Hillary Clinton campaign were released, documenting speeches, and outlines of key moments during the elections. It caused an uproar, and people scrambled to point fingers. Evidence pointed towards a hacker group associated with Russia called the Fancy Bears. Democrats attempted to clean up the mess; Podesta warned online that the e-mails may have been edited to fit a certain narrative.

Far right fringe groups, meeting on subreddits and message boards, combed through the e-mails. They were desperate to look for any sort of wrongdoing, and after looking at a series of e-mails, they were convinced they had their breakthrough. This series of e-mails centered on The Comet Ping Pong, discussing dinner plans as well as campaign donations. James Alefantis, the owner of The Comet Ping Pong and an ardent Democrat, was planning to pledge a wealth of money to the campaign. It seemed mostly like routine politicking- well, to everyone, it seemed, except for a certain section of the internet located on the infamous website 4chan.

4chan is, officially, a message board meant to discuss music, books, T.V. shows, and any other interest you may have. Unofficially however, it’s a volatile part of the internet, a place where the alt-right flourishes. It’s given us some of the internet’s most prominent memes — many of which are used primarily in offensive contexts — such as Pepe the Frog, Wojaks, and rage comics.

4chan also provided a foundation for The Comet Ping Pong shooting and the later formation of the infamous Qanon theory: Pizzagate.

According to the original members of the Pizzagate thread (which is now defunct, but you can access screenshots of it on various corners of the internet), Hillary Clinton and other figures in the Democratic party used the pizzeria as a front for a child trafficking ring. They lured children to the pizzeria before abducting them, keeping them in the basement and having them perform horrific acts. Qanon alleged that the word pizza, used multiple times in the original e-mail chain, had a double meaning, referencing planned abuses to be acted out against these hypothetical children.

The theory was disproved multiple times, first by those accused and then by the Washington, D.C. police. That didn’t stop the theories from circulating on 4chan, before spreading to Reddit and Twitter. It simply seemed to add fuel to the flames of suspicion, as Trump supporters and white supremacists echoed these claims.

Alefantis began to receive a barrage of death threats from those that believed the theory, and they accused him of being a pedophile, and threatened to torture him. The employees at The Comet Ping Pong began to receive similar attacks. It got so bad that the Alefantis called the FBI multiple times, begging them for their help. Each time, the FBI ignored his pleas, stating that unless these messages contained a ‘specific threat,’ in other words, a specific date and time when these alleged attacks against Alefantis were supposed to take place, there was nothing that they could do.

This horrific event happened because of the moral panic that spurred it. Moral panics, a widespread fear based on the idea that some behavior or group poses a ‘threat’ to society, have been a part of society for centuries. Moral panics often fester due to hearsay, fueled by rhetoric from those in power and regurgitated by media figureheads.

Moral panics thrive on deep rooted societal fears of the ‘other.’ The other can be any particular group of people, whether due to their race, ethnicity, sexuality, or other various factors. While a moral panic may explicitly go after any group of people, in practice, it targets groups considered different from the norm. Stereotypes are enforced in order to bolster the public’s agitation, widening both real and perceived differences between groups, in order to bolster the in groups opposition to the out group.

In 18th century London, public fascination surrounding criminals was whipped up into a frenzy. Newspapers, periodicals, and biographies centering the lives of criminals were in vogue, with information regarding daily court procedures adding to the canon of crime literature during this era. Part of this was compounded by external factors, namely a lack of any really interesting news happening either domestically or overseas to warrant reporting. In an era featuring the Silesian Wars, King George’s War, and The War of Jenkins, this represented a lull in the constant news about military operations both at home and overseas. The public was bored, and the press was itching for something to write about.

Late in the summer of 1744 C.E., a shift happened: the media reported a huge spike in violent robberies. Though there had been violent robberies taking place, they were more self-contained incidents, not indicative of any widespread collapse of society. The press, however, ran with it, and the public grew fraught with nerves. Patrols were instituted, and London’s middle class lobbied for a tougher stance on crime. Panic spread throughout the streets as neighbors turned on each other, accusing one another of being behind the robberies.

Moral panics, however, tend to be short lived. By January 1745 C.E., the news had shifted to covering other topics, with the panic over the crime wave fading into the background. It was almost as if it had never happened at all.

However, despite the sudden recession in fantastic articles covering the so-called crime boom, the repercussions of this moral panic still impacted London. From 1747 to 1755 C.E., more waves of panic ensued over alleged rises in organized crime, leading to stricter policies in the administration of criminal law.

Moral panics can resurface at any time, justifying exclusionist policies and gruesome displays of violence against the out groups. Take for instance the Wurzburg Witch Hunts from 1625–1631 C.E., in which, after an intense period of war between Protestants and Catholics, a mass hysteria led to witchcraft accusations. Around 1,246 people were executed, making this one of the largest mass witch trials in European history. Most of the accused witches were outcasts in some way, with some being travelers in the area who the local townspeople didn’t recognize.

Similar witch trials popped up in Europe throughout the years, causing mass harm to the populace. The justifications for it, while different, always held a similar notion: the perceived ‘destruction’ of society.

This sort of thinking isn’t limited to the past. Going back to The Comet Ping Pong, it’s present in the modern day as well. The Hays Code in the 1930’s and McCarthyism in the 1950’s, for instance, were both offshoots of this same paranoia, heightened by societal unrest and devastation.

The Hays Code was instituted during the Great Depression, when unemployment was sky high in the United States. After the lavishness of the 1920’s, the Hays Code was used as a way to combat against the perceived immorality of the past decade. Written by a Jesuit priest named Will H. Hays, it created a series of “moral” guidelines for films. It banned anything that could promote self-proclaimed negative values from the screen, such as violence or nudity. The villains in a movie had to always lose, while the heroes — usually in a position of authority — unanimously won. “Sympathy for criminals” allowed the villains of the story to be seen in a human light, and as a result, the Hays Code viewed any aspect of a film that could serve to humanize the antagonists as a morally corrupting factor. This code also worked to actively remove discussions regarding race or gender from the screen, attempting to hold fast to conservative values. Interracial relationships and ridicule of the clergy are, for example, two factors that were heavily censored out of movies due to these codes.

The ‘Red Scare’ is a term used to describe the utter paranoia surrounding Communism in 1950’s America. Leaders and politicians would often warn the public about “subversive” Communist threats in America, and of how they could be in seemingly safe facets of society. Your local school teacher, the head of a local union, a journalist — all of these people could be potential Communists. This fear would soon be harnessed by Senator McCarthy, who proposed a solution that would eventually lead to McCarthyism. McCarthyism sought to rid the country of supposed Communist influence through any means necessary, often accusing people of being communists at random. Hundreds of people lost their careers, and had their reputations tarnished because of the fallout of McCarthyism.

One of the more well-known panics began in the 1980’s, called the Satanic Panic. The seeds of it were planted in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Cults, such as the Manson Crime Family and the People’s Temple, had left an imprint of fear amongst Americans. The publishing of the Satanic Bible by Anton Lavey, a foundational text of the Satanic Temple, also helped to spur panic. It didn’t matter that the Satanic Temple was explicitly a peaceful organization who supported freedom of expression; the word ‘Satanic’ was enough to get the population in a frenzy.

Around this time period was also the rise of the New Left. Comprising multiple political ideologies, they were united by the fight for freedom and equality. The New Left focused more on social issues than the Old Left, where labor issues were more prominent. The Black Panthers, the anti-war movement, and the gay rights movement are all facets of the New Left, agitating for social change.

Publications such as Satan Seller and Satanic Rituals changed the dynamics of this outrage. Both Satan Seller and Satanic Rituals were allegedly true accounts of forced subservience to the devil in American homes, where the authors were forced to undergo satanic rituals and abused horrifically. The books spread like wildfire, creating an idea that dark, occultist rituals had become a facet of everyday life. People were convinced that the devil was out to get them, and Evangelical Christianity boomed. In the 1950’s, 57% of America belonged to a church; in the span of 10 years, this number increased to 63.3%. While on the surface this number may seem rather innocuous (after all, an increase of around 6% isn’t a huge figure), this is, in reality, the highest percentage of church-goers in American history.

What really marked the Satanic Panic as we know it today was the release of Michelle Remembers, a book written by Michelle Smith about her alleged experience with satanic abuse. The descriptions inside are horrific: child trafficking and horrendous abuse. Michelle recounts being used as a vehicle to raise Satan, being locked up in the attic and not allowed contact with the outside world. It played on the fears of the population, making neighbors stare at each other suspiciously over their fences, wondering if their neighbor was a satanist.

The book, released on November 1st, 1988, was later proven to be false. Michelle and her therapist turned husband (who co-wrote the book) were unable to bring up evidence to substantiate any one of her claims. This, however, was of little to no consequence, as the damage had already been done. Dungeons and Dragons players and Goth subculture among other groups were seen as countercultural, the territory of societal “freaks.” Authority figures fear mongered about corrupting influences, and a return to old school values — religiosity, strict gender divides, and the survival of the nuclear family, for example — was pushed by people all throughout the country.

During this wave, day care centers came under scrutiny. Parents accused day care centers of being havens for abuse, where animal murder and child abuse occurred on the daily. Day care workers were targeted en masse and brought to court under charges of satanic abuse. Of over 1,200 cases, almost none of them had substantiated their claims. It’s likely that the children who testified to the abuse were manipulated by authority figures and therapists, their statements taken out of context and twisted to put innocent people in jail. To this day, there are still people serving out sentences for satanic abuse, even though many of these cases have been appealed.

In 2024, these same fears have resurfaced. One of the leading factors of this revival is Qanon, a far-right political theory that grew popular amongst conservatives in 2017. Qanon claims that amongst the public lie shadowy figures part of a hidden, satanic cabal, who ritualistically torture children and use their blood for nefarious designs. Leading back to Pizzagate and the Satanic Panic, we can see the obvious ties between these three theories, as well as a common theme: using child abuse as a means to propagandize against political enemies.

When asked about her observations of the current moral panic engulfing the country, Haley Plummer ’24 said “I think politicians have been able to play into moral panics as a way of strengthening campaigns, presenting themselves as someone who can solve the perceived issue behind the panic. That’s forced me to be very critical of what I’m consuming to assess, if what a candidate is talking about is actually a real problem, or just a hot topic that they are currently trying to capitalize off of.”

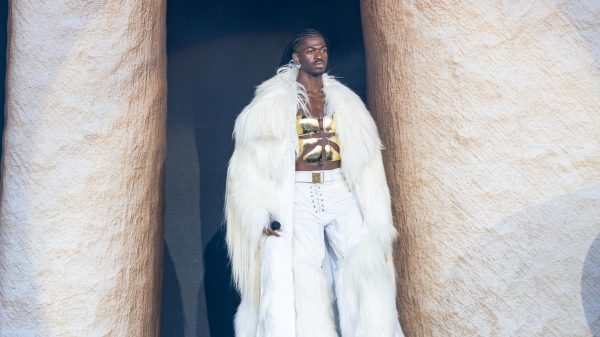

While Qanon focused more on political leaders, the current panic also goes after the media, specifically songwriters. Following in the footsteps of conservatives who screamed in fear over K.I.S.S, artists such as Lil Nas X and Sam Smith have been put under public scrutiny for content alleged to spread the words of satanism. It’s also not a coincidence that many of the stars targeted by this hysteria have almost always been members of the LGBTQ+ community. In tandem with the rise of laws targeting the LGBTQ+ community, these accusations feed into rising levels of transphobia across the country.

In Florida, for instance, laws have been passed limiting the rights of trans people to receive gender affirming care. While Florida is the most obvious example, this same rhetoric has spread throughout the country, even festering in cities thought of as overwhelmingly liberal. The new scapegoats are gender rebels and teachers, whose jobs are to expand the minds of others.

While there has been overwhelming public backlash against these policies, there’s also been a reverse reaction of doubling down on these conspiracy theories. As the 2024 election begins and tensions rise, it’s evident that the nation is more divided than ever. In the midst of outbreaks of deadly diseases and global wars ravaging whole countries, people will cling to whatever promises to give them a sense of security — even if that means destroying the lives of others to do it.

Moral panics, a widespread fear based on the idea that some behavior or group poses a ‘threat’ to society, have been a part of society for centuries. Moral panics often fester due to hearsay, fueled by rhetoric from those in power and regurgitated by media figureheads.