“I killed one man to save 100,000.” Those were the words of Charlotte Corday as she awaited her sentence from the revolutionary tribunal. The crime: the murder of Jean-Paul Marat, an esteemed French journalist and politician. As she proudly stood before the masses, people wondered what drove the twenty-four-year-old to commit the murder.

The Beginnings

On July 27th, 1768 in Saint-Saturnin Normandy, a young girl by the name of Marie-Anne-Charlotte Corday d’Armont, fondly referred to by her family as Marie, was born. Corday’s family members were fallen aristocrats: her father, Jacques-François de Corday d’Armont, was descended from the renowned dramatist Pierre Corneille and her mother, Charlotte-Marie Gaultier des Authieux, was descended from a French noble family.

Tragedy struck for the Corday d’Armont family in April of 1782, when Charlotte Corday’s mother and one of her sisters passed away. The family had a hard time processing their deaths, especially Corday’s father, who would later send her and her sister Eleonore to Caen to live with their aunt in a convent called Abbaye-aux-Dames.

In the convent, Corday received a superb education, since she was allowed freedom of thought and the means to pursue knowledge. As a young woman, Corday would become acquainted with works of enlightenment thinkers of the time like Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Not only engrossed in contemporary works, Corday was also well read in the works of Ancient Greece and Rome. She was highly influenced by the ideas of the Roman republic and as Corday put it herself, she was a republican before the revolution.

By the start of 1789, the tensions brewing in France would come to a boiling point. The extravagance of aristocrats and the unfair taxes led to widespread discontent from the Third Estate, which was the majority of the population in France. Upscale protests within France like the Storming of the Bastille and the Women’s March on Versailles caused by the discontent were soon to follow.

Political Involvement

Despite her aristocratic background, Corday was initially in support of the earlier revolution. She expressed her favor of the 1789 Declaration of Man and Citizen and the August Decrees, acts that aided the lower class. This put Corday in a rough position with her family who were royalists supporting the king.

But as the revolution started getting more radical, Corday’s views started to change. In 1790, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy was passed, closing down all convents and monasteries. This forced Corday to leave the convent she called home for eight years.

After leaving the convent, Corday opted to live with her cousin Madame de Bretteville to stay in Caen instead of going to live with her father. Despite their differing political views, Corday would form a close relationship with her cousin.

While living in Caen, Corday started to get increasingly involved with the Girondin faction, frequently attending their meetings and listening to their speeches. The faction advocated for a constitutional monarchy and less extreme policies, views that Corday agreed with.

However, as the revolution progressed, the influence of moderate groups like the Girondins dwindled as more extreme groups came to power.

The most notable of these radical groups in France were the Jacobins, who supported a complete upheaval of the French monarchy. Their extreme policies had started getting more attention and popularity in France. Like most other Girondins, Corday did not like the path the Jacobins were leading France.

She was absolutely disgusted by their actions like the September massacre, as to her, they were unnecessarily cruel and violent.

Corday also had personal misgivings towards the Jacobins, as they were responsible for the execution of Abbé Gombault, the minister who gave Corday’s mother her last rites, which were prayers given to a dying Christian. The combination of Corday’s personal opinion of the Jacobins and her involvement in the Girondin party led her to attempt to make a change to save France.

Picking a target

She thought that it could only be done through the assassination of Jean Paul Marat, one of the Jacobins’ most prominent members.

Marat was a politician and the author of the well known radical French newspaper l’ami du peuple. He was a great enemy of the Girondin party, as he was a leader in many Girondin arrests, and played a key role in kicking the Girondins out of the national convention.

Marat’s actions would make Girondins, who fled to Caen, distribute pamphlets condemning him. Their contempt was certainly not subtle, with many pamphlets stating “Let Marat’s head fall and the Republic is saved… Purge France of this man of blood… Marat sees the Public Safety only “in a river of blood; well then his own must flow, for his head must fall to save two hundred thousand others.”

Considering Corday lived in Caen, it wasn’t surprising when she labeled Marat as the illness that was plaguing France. She believed that she would be doing her country an act of service by getting rid of him, and that with his disappearance the violent extremism would come to an end. Corday justifies her murder of Marat in her “Address to the French, Friends of Law and Peace”.

She wrote “Marat, whose name alone presents the image of all crime, in falling under the avenging steel, shakes the Mountain and makes Danton grow pale. Robespierre, those other brigands seated upon the bloody throne, are enveloped in the lightning which the avenging gods of humanity only suspend, without doubt, to render their fall more glittering and to affright all those who would be tempted to establish their fortunes on the ruins of an abused people!”

But why did Corday consider Marat the primary threat compared to other notable political leaders of the time ?

According to Professor Nina Rattner Gelbart, author and historian of sciences at Occidental College, “He had a newspaper. The friend of the people that was how it was mostly known. He was also considered a l’ami du peuple, a friend of the people. Danton could come up and give speeches, Robespierre could come up and give speeches in the convention. Marat had a much broader following as he had a newspaper. She saw him as the most dangerous.”

The Assassination of Marat

With little hesitation, Charlotte Corday planned Marat’s assassination. On July 9th, 1793, Charlotte Corday would leave her cousin’s house for Paris.

On the same day she would also address a letter to her father. In this letter she tells her father that she would be leaving for England and asks him not to forget her. The reality was that Corday’s destination was not going to be England but Paris.

When Charlotte Corday arrived in Paris on July 11th, 1973, she planned to assassinate Marat on the Fête de la Fédération as there would be a large crowd gathered around for the celebration; she wanted to make a public example out of Marat.

However, unknown to Corday, Marat had been confined to his home due to a terrible disease. She was forced to make changes to her plans and had to settle with killing Marat in his home instead.

Entering Marat’s house wasn’t an easy task as Marat was not allowing any visitors in his home. Corday’s first few attempts to enter Marat’s residence miserably failed. On her first attempt, Corday was declined by Marat’s sister-in-law. On her second attempt, she was once again declined, this time by Marat’s fiancée Simone Évrard, who was suspicious of how desperately Corday wanted to meet Marat. Perhaps it was the third time that was the charm, but when Corday tried for a final time on July 13th, 1793, she succeeded. She was let into the estate by Marat himself in spite of the better judgment of his sister-in-law and his fiancée.

He had agreed to a meeting with Corday after she promised to give him news on Girondin traitors who were scheming to revert the revolution.

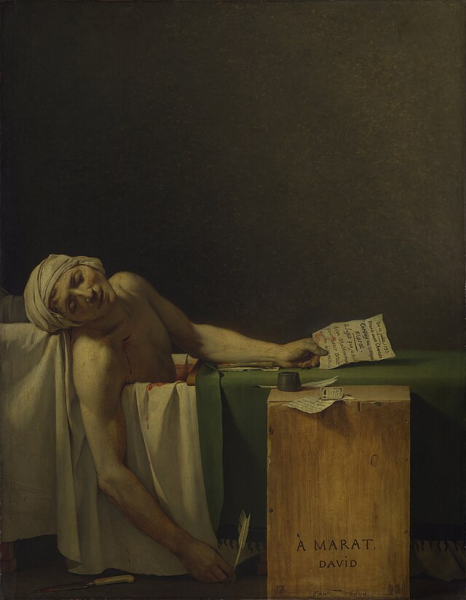

Marat was in his bathtub asking for the names of the Girondin traitors as Corday’s knife quickly plummeted into his chest. Marat screamed for his fiancée to come help him, but it was much too late. The stab wound had been fatal and when others arrived at the scene, Marat was no longer breathing.

The news of Marat’s death spread like wildfire throughout France.

The friend of the people was dead!

The Arrest and Execution

The politicians and the public were horrified. They couldn’t fathom any reasons why Charlotte Corday, a young noblewoman, had gone through such extremes to kill Marat.

Charlotte Corday was quickly imprisoned and questioned. She was put on trial and cross examined three times before the revolutionary tribunal, two of which by the tribunal president Jacques-Bernard-Marie Montané himself.

Montané and other members of the jury asked Corday why she had committed the deed and who had sent her. Corday claimed that she had the idea herself and committed it individually.

When asked why she had committed the deed, Corday said, “With this one dead, the others, perhaps, will be afraid,” expressing her hope that her deeds would discourage the Jacobins’ actions.

Officials however didn’t believe Corday, not believing that a woman could be capable of a politically motivated murder.

While in prison, Corday wrote another letter addressed to her father. She wrote, “Forgive me, my dear papa, for having disposed of my existence without your permission,” alluding to her upcoming execution.

For her last request, which was approved, Corday asked for a portrait that others could remember her by. To accomplish this, Corday writes another letter in prison, this time to convince the Jacobins to let her have her portrait taken. “It’s a very cleverly worded letter, as she wanted to be portrayed in a flattering way. She thought that if she admitted that she had done something criminal, and told them, ‘You might be interested in having my portrait because I committed a crime,’ that it would work, and it did,” Professor Gelbart said.

The painter appointed was Jean Paul Hauer, who had a sympathetic portrait made of her. Even to this very day, Hauer’s portrait is one of the most well known images of Corday.

On July 17th, 1793, ten days before her twenty-fifth birthday, Charlotte Corday was executed.

After her death, many French officials still didn’t believe that Corday had the idea and carried out the murder of Marat herself. After all, Charlotte Corday was a woman, and how was it even possible for women to commit politically motivated murders and succeed at it?

They ordered an autopsy to be done on her to see if she was a virgin. They thought that she must have certainly been a lover of Corday’s who came up with the radical idea and goaded her into doing it. The tribunal was ultimately proven wrong as the results of the autopsy showed that Corday indeed was a virgin, proving that no male lover could be credited for the murder.

The Aftermath

Despite Corday’s hopes, the murder of Marat did not quell extremism in France. On the contrary, the murder of Marat only escalated the extremism of the Jacobins, eventually leading to the reign of terror.

“Marat being out of the picture made Robespierre much more powerful. He became suspicious of everybody, so the laws passed under his reign as he was in charge then were laws like the laws of suspect. The law of suspect was a terrible thing, as Frenchmen could denounce each other. They could say they thought their neighbors were saying bad things. That is when heads began to roll. The executions came to really pick up, with Robespierre making everyone suspicious of everyone else,” said Professor Gelbart.

After his death, Marat was turned into a martyr. He was idolized, compared to Jesus and his body was embalmed for all of France to see. On the streets of Paris in 1793, one could hear Marat’s songs honoring Marat and could find statues of him throughout France. The statue of Marat even replaced the Virgin Mary on Rue aux Ours. When the Jacobins established their ‘cult of supreme being,’ Marat was named a quasi-saint.

When women in France heard that Corday murdered Marat, they were horrified. They felt that Corday’s actions reflected badly on them, and therefore condemned her and tried to disassociate themselves from her.

Even though Marat wasn’t universally liked, he was still very popular due to his well known newspaper. The fact that a woman had killed Marat who was advocating for the underdogs in the French Revolution reflected badly on French women in general in the eyes of the general public. Corday’s actions made people in general more fearful and suspicious of women. In fact, shortly after Marat was killed, women’s clubs were closed.

Legacy

Compared to her reputation during the French Revolution, Corday’s reputation has greatly improved in the modern day. Today, people hold contrasting views of Corday; some view her as a conservative aristocrat silencing the friend of the people, and others as a revolutionary hero attempting to save France.

Corday has, like Marat, become a martyr of her own right to those who saw her as a hero in the revolution.

Despite differing views on Corday, it is undeniable that she subverted common perceptions of women of the time with her radical actions. Corday showed men of the time the courage, independence, and individual autonomy that women have.

While Corday has been dead for over 230 years, her story lives on through art and literature. There have been many portraits made of Charlotte Corday both before and after her death as well as works of literature and plays written about her. In 1847, writer Alphonse de Lamartine coined Corday ‘the angel of assassination.’ Corday has been referred to by this name in literature and countless other mediums since then.

From Victor Hugo’s renowned novel Les Misérables, where Corday is briefly compared to a revolutionary hero, to the more recent 2014 cameo in the game Assassin’s Creed, Charlotte Corday lives on.

“There is a long tradition of preservation through art, from Roman sculptures of famous people to paintings. We immortalize them,” said Mr. Walter Giorgis-Blessent, an Advanced Placement French teacher at Bronx Science.

Whether it is through art or literature, the legacy of Charlotte Corday has been forever immortalized.

The combination of Charlotte Corday’s personal opinion of the Jacobins and her involvement in the Girondin party led her to attempt to make a change to save France. She thought that it could only be done through the assassination of Jean Paul Marat.