Sinful History: The Strange and Unknown Origins of the Seven Deadly Sins

The Seven Deadly Sins are said to have originated from a list of eight; how did the list slowly transform into the modern list of seven?

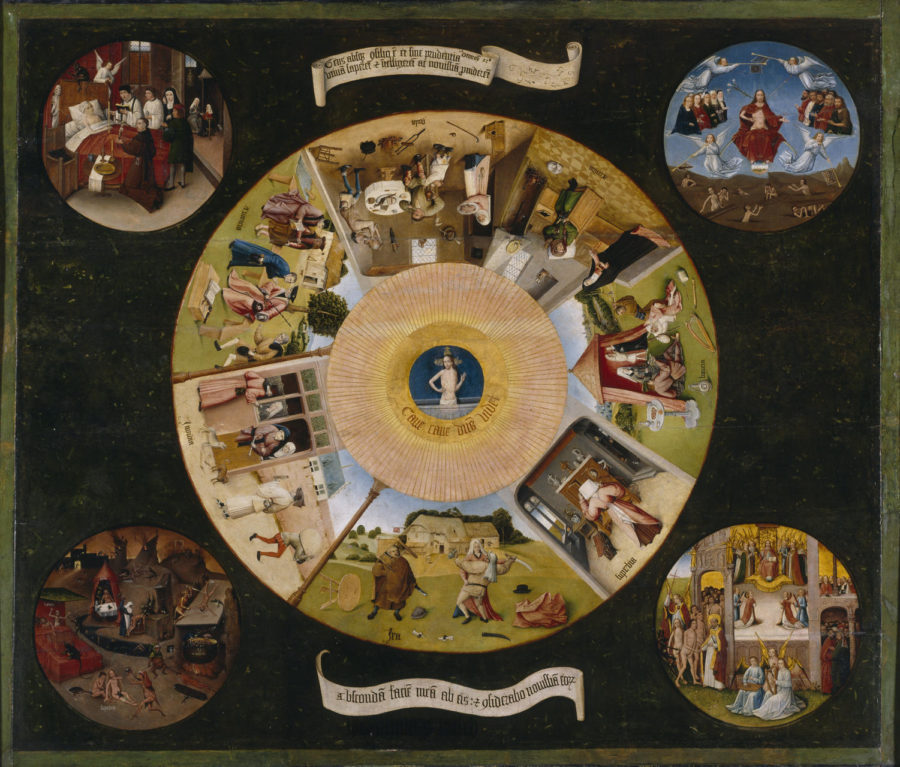

Hieronymus Bosch or follower, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things” is a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century painting commonly attributed to Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch. The divided sections in the central circle represent, clockwise from the top, the Seven Deadly Sins: Gluttony, Sloth, Lust, Pride, Wrath, Envy, and Greed. Jesus is depicted in the center of the sins. The surrounding Four Last Things are, clockwise from the top-left corner: Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell. It is on view at the Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain.

Lust, Envy, Gluttony, Sloth, Greed, Wrath, and Pride. Despite never being explicitly stated in the Bible, these seven nouns are an essential part of Christian doctrine. Collectively known as the “Seven Deadly Sins,” these seven concepts are so malicious that the mere thought of them is enough for a condemnation of eternal torment in Hell.

Their roots run back to 375 AD, when Christian monk Evagrius Ponticus had written a letter describing the “Eight Tempting Thoughts/Demons”: Gluttony, Sexual Immorality (or Lust), Avarice (Love of Money, or Greed), Sadness (or Gloominess), Anger (or Wrath), Acedia (or Sloth), Vainglory, and Pride. Then, in 590 AD, Pope Gregory I – also known as Pope Gregory the Great – adjusted the list to the modern one and used his influence to popularize the now-dubbed “Seven Deadly Sins.”

However, Ponticus’s letter was enclosed in a Praktikos, a guide only intended for other monks as a warning of temptations that could cause faltering in their strict, ascetic lifestyles (which typically entailed fleeing to Egyptian deserts to live in seclusion), and thus never received much attention from the public eye. In fact, Ponticus’s thoughts on sin were largely considered heretical because of his denial of Original Sin – a major doctrine that Adam and Eve’s disobedient sin of falling to temptation in the Garden of Eden is inherited by every human being, as their descendants, and must be washed away through the holy sacrament of Baptism. Moreover, most of his works have been lost, attributed to other authors, or simply left untranslated in Greek.

Disclaimers

First, there are a few Bible verses in which some of the Seven Deadly Sins are named, but all seven are never mentioned together. Twice, Jesus comes the closest to explaining the list. The first comes from the Gospel of Matthew. “For out of the heart come evil thoughts — murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false testimony, slander” (Matthew 15:19). However, these are more likely related to the Ten Commandments, which punish murder (6th Commandment), adultery/coveting your neighbor’s wife (7th and 10th), theft (8th), and false testimony/slander (9th). The second comes from the Gospel of Luke. “An impure spirit comes out of a person, it goes through arid places seeking rest and does not find it. Then it says, ‘I will return to the house I left.’ When it arrives, it finds the house swept clean and put in order. Then it goes and takes seven other spirits more wicked than itself, and they go in and live there. And the final condition of that person is worse than the first.” (Luke 11:24-26).

Second, though Ponticus is commonly regarded as the original author of the Seven Deadly Sins, there are earlier occasions where other writers describe a similar variant of the concept. Additionally, the consideration of the items on Ponticus’s list as malicious is one of great antiquity. Medievalist and Harvard professor Morton W. Bloomfield attempts to trace their history back to Hellenistic times in his 1941 article, The Origin of the Concept of the Seven Cardinal Sins. Anglican priest Angela Tilby suggests that second-to-third century Greek philosopher Diogenes Laertius was the true predecessor in her 2009 book, The Seven Deadly Sins: Their origin in the spiritual teaching of Evagrius the Hermit (the link leads to a preview of the book).

Lastly, in his writings, Ponticus specifically uses the term “logismoi,” or thought, when describing his eight sins. This was warranted by his heretical view on the nature of sin: that sin is developed, not immediately introduced, and can be prevented. This was also the reason why he wrote his works to begin with; he believed that the Eight Tempting Thoughts were just that — temptations that monks would inevitably face and could lead to disaster, but were ultimately avoidable. “We cannot [control] whether these [tempting-thoughts] can agitate the soul or not; but whether they remain [in us] or not, and whether they arouse the passions or not – that we can [control],” wrote Ponticus in Praktikos. However, as time passed, the eight grew from the mere concerns of a monk to larger, more widespread problems. Additionally, Ponticus had also believed that these temptations sought to take humans away from their innate innocence, gifted to us through our being made in God’s image. This belief, too, changed to one that villainized humans as being naturally sinful. Therefore, the words associated with them changed to be more foreboding: “Principal,” “Deadly,” “Cardinal,” “Vice,” and “Sin.”

Evagrius Ponticus vs. John Cassian

John Cassian, a monk and student of Ponticus, is credited with translating Ponticus’s works to Latin, which aided in increasing their popularity. Cassian, though heavily influenced and inspired by Ponticus’s works (often to the point of near-impossible distinction), nevertheless had a much bigger role than that of a mere translator. He had his own beliefs and had adjusted some of the teachings to be more coherent and thus better be accepted into society.

Around 417-419 AD, Cassian had published a twelve book series: Ionhannis Cassiani De Institutis Coenobiorum Et De Octo Principalium Vitiorum Remediis Libri XII, Latin for The Twelve Books of John Cassian on the Institutes of Coenobia and on the Remedies for the Eight Principal Thoughts and often referred to as Institutes. The last eight books of Institutes are each dedicated to one of Ponticus’s Eight Tempting Thoughts. Cassian translates them as Gluttony, Fornification, Covetousness (or Love of Money, ie: Avarice/Greed), Anger, Dejection, Accidia (or Acedia), Vainglory, and Pride under the title of the “Eight Principal Thoughts.”

Cassian further elaborates on the Eight Principal Thoughts in the 420s through Conferences 5 – the fifth book of a twenty-four book series titled Collationes Patrum XXIV, Latin for Collations of the Fathers or Conferences of the Egyptian Monks, and shortened as Collections or Conferences.

Though Cassian’s writings translated Ponticus’s Tempting Thoughts under different names, the core essence of what those names embodied remained, demonstrated through the elaborations in Collections that match up with Ponticus’s writings. However, given the inevitable differences between the two, there were some changes that Cassian made in his list, perhaps for the better in helping their popularization.

One of Cassian’s additions was reaffirmation. In Chapter 18 of Conferences 5, Cassian assures that there are eight Principal Thoughts, writing “Everybody is perfectly agreed that there are eight principal faults which affect a monk.” This may have been to distance himself from the less-popular Ponticus, who had no written records of a reasoning for why he listed specifically eight thoughts.

In fact, Ponticus’s works were largely disorganized and inconsistent with the Eight Tempting Thoughts. Though Praktikos, considerations its direct listing and definitions, is the most famous work with this concept, the thoughts are included in other writings: On the Eight Evil Spirits; On the Vices Opposed to the Virtues, alternatively On the Evil Adversaries of the Virtues, short descriptions of the thoughts; Antirrhetikos, or Refutations, a collection of Biblical quotes used to refute the Eight Tempting Thoughts separated into eight chapters, each dedicated to a different thought; On Thoughts; and Exhortation to Monks.

In On the Vices Opposed to the Virtues, Ponticus surprisingly deviates from the rest of his works, creating a list of nine with Envy (which Pope Gregory would later reintroduce), who sat between Vainglory and Pride. Otherwise, it and Antirrhetikos followed the same order of thoughts as Praktikos – Gluttony, Sexual Immorality, Avarice, Sadness, Anger, Acedia, Vainglory, and Pride. On Thoughts lists the familiar eight thoughts, though under new relationships. Interestingly, Gluttony, Avarice, and Vainglory are listed as the three main thoughts which lead to the rest; Gluttony led to Fornification and Avarice – with the latter then leading to Sadness and Pride – and Anger led to Vainglory. Exhortation to Monks orders them in a traditional list again, though the items are different: Gluttony, Fornication, Avarice, Corporeal Concerns, the Wandering Mind (essentially Acedia), Anger, Acedia (again), Sadness, and Pride. (This information is based on quotations from a research paper, as there are no easily-accessible English translations of many of Ponticus’s works.)

In On the Eight Evil Spirits, Ponticus uses the order Gluttony, Fornication, Avarice, Anger, Depression, Accidie, Vainglory, and Pride – the same order that Cassian uses in Institutes. Cassian’s works stay loyal to this order, providing a firm and reliable basis on which the Eight Principal Thoughts could grow.

Lastly, in Institutions XII, Cassian writes that Pride is the “root of all evil” and “faults…spring from the evil of pride,” believing that it was the worst sin (which Pope Gregory would later elaborate on). Ponticus, however, had believed that Acedia was the worst of the sins; in Praktikos, he writes that it is “the most burdensome of all the demons.” Cassian’s decision most likely stemmed from Ponticus’s description of Pride as being able to “conduct the soul to the very worst fall” in Praktikos.

Regardless, both of Cassian’s works, Institutes and Conferences, were extremely successful and granted Cassian high popularity. They would go on to continue being used and influence others (even after Cassian became shrouded in several controversies – the main one due to his later publishing of a rushed and disappointing treatise prosecuting the controversial teachings of archbishop Nestorius at the request of Pope Leo the Great, titled De Incarnatione Domini Contra Nestorium, Latin for On the Incarnation of the Lord Against Nestorius) who would eventually become important figures in the foundation of Chrisitanity. It is for this reason that Cassian is called a majorly influential figure in the foundation of Western monasticism.

Pope Gregory the Great

Gregorius Anicius, one of the many influenced by Cassian’s writings, was an avid monk, born to a wealthy family and received a good education amidst a time of turmoil, who had written several crucial works. He would later be elected to become Pope Gregory I in 590, though he is more commonly referred to as Pope Gregory the Great. Despite his initial unwillingness to accept the position, for he much preferred the monastic life, he eventually rose to the occasion, holding a fundamental role in the development of the Catholic Church. His title of “the Great” is a testament to his numerous contributions, as well as his being canonized as a saint and named a Doctor of the Church – a title reserved for saints whose works have contributed much to the Church and are considered classics.

Pope Gregory’s position as pope came with a lot of authority and impact, and he doubtless made several notable decisions during his time. A prominent example of his power comes from his moral initiative against the Lombards’ – a Germanic tribe – attempts at Italian conquest, demonstrated through his paying hostages’ ransoms. He had also made several other significant contributions, namely through aiding the poor and writing essential books and prayers.

Among several of his works is Moralia in Job, or Morals in [the Book of] Job, an extensive, multi-volume, multi-book series in which Pope Gregory comments on the Book of Job, a Gospel in the Bible. In Section [XLV] of Book XXXI, Volume III – The Sixth Part, Pope Gregory reestablishes the “Eight Tempting Thoughts” as the “Seven Principal Sins/Vices”: Vainglory, Envy, Anger, Melancholy, Avarice, Gluttony, and Lust.

Although Pope Gregory had removed Pride, he did not get rid of it entirely. Rather, he believed it was the “root of all evil” and put it above all the other sins, agreeing with Cassian. He explains, “For when pride, the queen of sins, has fully possessed a conquered heart, she surrenders it immediately to seven principal sins, as if to some of her generals, to lay it waste. And an army in truth follows these generals, because, doubtless, there spring up from them importunate hosts of sins…For, because He [God] grieved that we were held captive by these seven sins of pride, therefore our Redeemer [Jesus] came to the spiritual battle of our liberation [Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection], full of the spirit of sevenfold grace.”

Pope Gregory had also added Envy back into the list – which Ponticus stranded in On the Vices Opposed to the Virtues – as a combination of Vainglory and Pride. “From envy there spring hatred, whispering, detraction, exultation at the misfortunes of a neighbour, and affliction at his prosperity,” writes Pope Gregory. He believed that Envy was present in Genesis – the first book in the Bible containing the story of the Garden of Eden – and gave it a commanding role, similar to Pride and possibly inspired by Ponticus’s unique characterization in On Thoughts. Pope Gregory’s Moralia in Job opens with Section [I], which says, “The devil, through envy, inflicted the wound of pride on healthful man in Paradise [Adam].” Pope Gregory further elaborates on the importance of Envy in Section [XLV]; “For the first offspring of pride is vainglory, and this, when it hath corrupted the oppressed mind, presently begets envy. Because doubtless while it is seeking the power of an empty name, it feels envy against any one else being able to obtain it. Envy also generates anger; because the more the mind is pierced by the inward wound of envy, the more also is the gentleness of tranquillity lost.”

Additionally, he had combined Gloominess, Sloth, and parts of Ponticus’s Anger – for Ponticus believed Anger was a cause of Gloominess – under the new sin of ‘Melancholy.’ “From melancholy there arise malice, rancour, cowardice, despair, slothfulness in fulfilling the commands, and a wandering of the mind on unlawful objects,” describes Pope Gregory in Section [XLV].

Pope Gregory, motivated by his extreme beliefs on sin as an innate human trait – since they can all be identified in Adam and Eve’s fall and thus are inherited in us as their descendants – that causes straying from our all-powerful God, used his authority to spread of the Seven Deadly Sins as a principle and place his list as a standard. He also implemented several reforms to further promote discipline on avoiding the Seven Principal Vices. One enduring reform is his declaration of mandatory celibacy among all priests in the Roman Catholic Church. Though some believed that this issue was made to prevent ordained ministers’ sons from inheriting important Church property, it eventually evolved into an intense belief of sexual acts as forbidden and taboo, ultimately restricting the vice of Lust.

Saint Thomas Aquinas

With Pope Gregory’s immense influence, it was inevitable that someone inspired by him would later build upon his ideas. One such person was Thomas Aquinas, a thirteenth-century ordained minister and theologian. Aquinas wrote several significant works on the Catholic Church, among other acts, that would eventually earn his being canonized as a saint in 1323 and named a doctor of the Church in 1567 – titles that Pope Gregory similarly achieved. Additionally, parts of his body are kept at the Church of Jacobins in France as relics – a Catholic preservation process done to venerate and honor important individuals.

From 1265-1273, Aquinas wrote (though he died before it could be completed) his most famous work: Summa Theologica, or Summa Theologiae, a comprehensive, multi-part summary of the Catholic Church’s teachings thus far. Its format proposes a question, presents roughly three objections to said question, and includes Aquinas’s beliefs and response to those objections. The questions cover several Catholic topics, and Aquinas’s responses sources several other writers including Aristotle – whom Aquinas admired – and Pope Gregory.

Aquinas agrees with much of Pope Gregory’s thoughts on the Seven Principal Vices in Summa Theologica. In I-II:84:3 and I-II:84:4, Aquinas defines a capital vice with Pope Gregory’s words, writing, “In this way a capital vice is one from which other vices arise, chiefly by being their final cause, which origin is formal, as stated above. Wherefore a capital vice is not only the principle of others, but is also their director and, in a way, their leader: because the art or habit, to which the end belongs, is always the principle and the commander in matters concerning the means. Hence Gregory compares these capital vices to the ‘leaders of an army.’”

Additionally, in the first part of the second book – Prima Secundæ Partis, which covers Sins and Vices –, Aquinas defends the existence of the Seven Deadly Sins. In his response to the objection, “It would seem that we ought not to reckon seven capital vices, viz. [namely] Vainglory, Envy, Anger, Sloth, Covetousness, Gluttony, Lust. For sins are opposed to virtues. But there are four principal virtues, as stated above. Therefore there are only four principal or capital vices,” he writes, “Virtue and vice do not originate in the same way: since virtue is caused by the subordination of the appetite to reason, or to the immutable good, which is God, whereas vice arises from the appetite for mutable good. Wherefore there is no need for the principal vices to be contrary to the principal virtues” (I-II:84:4). (ie: Although there are only Four Principal Virtues, there can be Seven Capital Vices because they have different origins. Therefore, those seven – Vainglory, Envy, Anger, Sloth, Covetousness, Gluttony, and Lust – should not be ignored.)

Aquinas reestablishes Pride – like Cassian and Pope Gregory did – as the root of the other sins in I-II:84:2, and does the same for Covetousness (Greed) in I-II:84:I and II-II:118:7. He has individual responses defending controversial sins: Sloth in II-II: 35:4, which Pope Gregory had excluded; Envy in II-II:36:4, which Ponticus used once and Pope Gregory reintroduced; and Anger in I-II:46:1 (Though, Aquinas describes Anger as a “Special Passion” in this response. In II-II:34:5, Aquinas also denies Hatred as a Capital Sin, but Hatred and Anger are different.). Although Aquinas did believe in the remaining sins (evident in the previous paragraph), he most likely deemed elaborations to the extent of the aforementioned sins unnecessary, as they were the more accepted ones of the list.

With his large presence in the Catholic community, Aquinas’s words in Summa Theologica were able to further spread the Seven Deadly Sins.

Dante Alighieri

One of the most famous writings involving the Seven Deadly Sins comes from Italian writer Dante Alighieri’s fourteenth-century Divine Comedy, an allegorical, three-part long poem consisting of Inferno, Italian for Hell; Purgatorio, Italian for Purgatory; and Paradiso, Italian for Paradise.

In Purgatorio, the second part, Alighieri describes his fictional journey through Purgatory. Alighieri’s Purgatory is divided into Seven Terraces for the fitting purgings of and purifications from the Seven Deadly Sins: Pride, Envy, Wrath, Sloth, Greed, Gluttony, and Lust – which is now the modern-day list of sins. He categorizes them in accordance with love; the first three (Pride, Envy, and Wrath) are the result of a love to harm others, the fourth (Sloth) is of a lack of love, and the last three (Greed, Gluttony, and Lust) are of excessive material love.

His removal of Vainglory and its replacement with Pride – and Pride’s subsequent dethroning from its sovereign role – seems to be influenced by Aquinas’s words and inspired by Cassian’s actions. In Summa Theologica II-II:36:4, during his justification for Envy’s being a Capital Vice, Aquinas references Pope Gregory’s statement of Envy coming from Vainglory, which came from Pride. John Cassian uses this to justify that Envy should not be considered a Principal Thought, while Aligheri appears to use it to justify why Vainglory should be excluded. Additionally, Aquinas had also defined Vainglory and Pride similarly and, since Pride is more prominent than Vainglory, Aligheri most likely deemed it irrelevant.

(You can read a deeper analytical and comparative dive into the Seven Deadly Sins’ representation in Divine Comedy versus other works in this essay.)

Pope John Paul II

Hitherto, the Seven Capital Vices were commonly accepted by many as an essential part of the Catholic faith despite not yet being officially recognized. Finally, centuries later in 1992, Pope John Paul II formalized the Seven Capital Vices as part of Catholic canon by promulgating the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which is a reference containing fundamental Catholic doctrines. The list recognizes Pope Gregory’s and John Cassian’s contributions, but not those of Thomas Aquinas or Dante Alighieri. Part Three, Section I Chapter 1 Article 8 Section V. The Proliferation of Sin states, “Vices can be classified according to the virtues they oppose, or also be linked to the capital sins which Christian experience has distinguished, following St. John Cassian and St. Gregory the Great. They are called ‘capital’ because they engender other sins, other vices. They are Pride, Avarice, Envy, Wrath, Lust, Gluttony, and Sloth.”

The Sins Defined

Ponticus’s original list had described the sins in respect to how they would tempt ascetic monks’ discipline and cause them to stray. As the sins veered towards larger-scale issues, their definitions broadened and deviated from their predecessors. (Note: The dictionary definition of the words are different from the definition of the sins, eg: The definition of ‘Gluttony’ is different from the definition of the ‘Sin of Gluttony.’) (For a more in-depth history of how these definitions came to be, you can watch this playlist from History Channel.)

Ascetic monks fasted and abstained from eating too much. Ponticus’s definition of Gluttony seems to be both positive and negative, though both are gastronomic; monks tempted by Gluttony may remain steadfast and “recall those of the brethren who have suffered these things [side-effects of fasting, abstaining, and being secluded from physicians],” while others may begin to hate the strict lifestyle for preventing them from eating and “tell them [others practicing self-control] all about their misfortunes and how this resulted from their asceticism.”

Ponticus describes Sexual Immorality in more abstract terms, perhaps out of fear that excess detail would drive him to the sin. An affected monk is compelled with “desiring for different bodies,” especially if they were previously strong in maintaining self-control, and thus all of their struggles towards holiness are invalidated. They hallucinate, presumably about sexual desires, that is, they “speak certain words and then hear them, as if the thing were actually there to be seen.”

Ascetic monks had no need to keep money, as they were secluded from society and had alternatives. Avarice, then, was a more direct violation of their lifestyles, and thus, unlike many of the other sins, Ponticus describes it as less of a catalyst and more of a result. Under the influence of Avarice, monks would despise their lifestyles because the lack of money resulted in unpleasant aspects: “long old age; hands powerless to work; hunger and disease yet to come; the bitterness of poverty; and the disgrace of receiving the necessities from others.”

Unlike other sins, Gloominess does not drive a monk to actively attempt leaving their lifestyle, but rather causes them to be miserable whilst maintaining it. It stems from “frustrated desires” and the sin of Anger as a result of the monk’s current lifestyle. They are painfully reminded that “home and parents and [the] former course of life” are “gone and cannot be recovered due to the present way of life.” This struggle is followed by a “second” sin, which has a stronger grasp than it would have had without the help of Gloominess because of a weakened will.

Anger maintains a strong grasp on a monk after it is first instilled. It starts as “indignation against a wrongdoer or a presumed wrongdoer,” and this initial indignation intensifies and lingers throughout the day, especially during prayers in which the monk needs to be calm and focused. The monk is haunted by this feeling, their soul turning “savage,” and the bitterness has nightly manifestations through “bodily weakness,” “pallor [paleness],” and “attacks from poisonous beasts.”

Ponticus gives Acedia the title of “the most burdensome of all the demons.” Acedia is specifically active in monks from 10 A.M. to 2 P.M., deluding them to believe that time has stopped. As a result, they neglect their duties, and time becomes their only interest to the extent of obsession in which the monk constantly “observe[s] the sun in order to see how much longer it is to [3 P.M.].” It then makes them feel hatred toward “his place, his way of life, and the work of his hands,” especially if he has recently experienced grief, because they resulted in a burdensome, lonely ascetic life in which the monk is separated from their beloved family and peaceful past life. [It is specifically stated that Acedia is the source of this hatred, not the sin of Anger; “No other demon comes immediately after this one (Acedia).”] Interestingly, Acedia has the potential to be good; the monk will be stricken with a strong desire to leave his perceived-as-painful lifestyle behind and flee, which must ultimately be received with affirmative acceptance and “a peaceful state and unspeakable joy.”

Vainglory is described as a sin which comes suddenly and unexpectedly. It, as the name suggests, demands validation, or glory, from other people – which is a normal sentiment to have, albeit Vainglory is a more excessive, dependent, and almost possessive desire for it, hence vain. Vainglory pushes monks to believe that their being ordained will come with much praise because of their supposed ability to perform miracles, seeing as Jesus accomplished several and received much worship for his miracles, and be overcome with an urge to “publish their efforts.” After instilling these “empty hopes” and fantasies in monks, Vainglory leaves and makes way for the sins of Pride, Sadness, and/or Sexual Immorality, either to pursue glory or to cope with an inability to do so.

Pride was one of the worst sins, written as being able to “conduct the soul to the very worst fall.” Pride prevented monks from accepting God’s help, made them become egotistical, not think of God as responsible for their successes, and look down on other people for believing otherwise – though thinking otherwise, in this case, would be more in line with the orthodox way of thinking. Pride also led an afflicted individual to the sins of Wrath and Sadness, as well as “complete insanity,” with insanity most likely referring to how strange it is for someone not to accept God as the most powerful and instead put themselves in that role.

Depictions in Art

The Seven Deadly Sins, as are many themes within Catholicism, are a major theme within art. This is partly due to the fact that they are merely concepts, which can be easily applied to several situations to add interest.

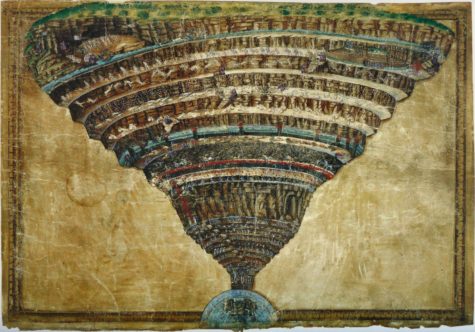

In addition to Dante Alighieri’s aforementioned Purgatorio, first and most well-received part, Inferno, also includes the Seven Deadly Sins – though to a lesser extent. Alighieri describes his fictional journey through Hell as guided by his idol: the Roman poet Virgil. In said depiction, Hell consists of nine concentric layered circles, the first (Limbo) being non-punishing, while the following eight are set up for the punishment of eight different sins that increase in severity the deeper and closer they are to the center. The eight circles punish: Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Wrath, Hearsay, Violence, Fraud, and Treachery. Though not entirely faithful to any listing of the Seven/Eight Tempting Thoughts, the second through fifth circles coincide with four of the commonly agreed-upon thoughts.

Another well-known attribution of the Seven Deadly Sins is often credited to John Wycliffe, a prominent figure in the Church whose work would later be essential during the Protestant Reformation. Written in the fifteenth century, The Lanterne of Light (in Old English) is a work describing the infamous Seven Princes of Hell, who represent the Seven Deadly Sins: Lucifer of Pride, Mammon of Greed, Asmodeus of Lust, Leviathan of Envy, Beelzebub of Gluttony, Satan of Wrath, and Belphegor of Sloth.

The Seven Deadly Sins are not limited to written works, though. Around the sixteenth century, a detailed painting titled The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (the first image in this article) was created depicting the titular Seven Deadly Sins in seven despicable scenarios forming a circle. In the center, a ring is divided into sections that represent, clockwise from the top: Gluttony as a drunkard, a gluttonous father-and-son pair, and a server; Sloth as a poorly-dressed sleeping man avoiding his work and prayers in the middle of the day; Lust as two couples, one being entertained by clowns; Pride as a woman admiring her reflection through a mirror held by a demon in an embellished room; Wrath as a woman stopping a bloody brawl between two peasants; Envy as a married couple envying a rich man’s bird while their married daughter, eyeing a large purse, accepts a rose from another rich man; and Greed as a corrupt judge pretending to listen to a case while secretly accepting a bribe in the presence of indifferent bystanders. Jesus is depicted in the center of the ring of sins. In the four corners of the painting are circles depicting, clockwise from the top-left corner: Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell.

The Seven Deadly Sins have inevitably appeared in modern times, as well. The Seven Deadly Sins by Nakaba Suzuki is a manga and anime series and perhaps the most recognizable example because of its title. Uniquely, it characterizes the main characters with the sins, making the otherwise malevolent traits benevolent.

Undoubtedly, the Seven Deadly Sins will continue being depicted in several aspects of life, and, despite unavoidable additional changes to the list, the core of this sinful concept will prevail as it has done for millennia.

“Wherefore a capital vice is not only the principle of others, but is also their director and, in a way, their leader: because the art or habit, to which the end belongs, is always the principle and the commander in matters concerning the means.”

Kathy Le is an Editor-in-Chief and Chief Graphic Designer for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook. She enjoys writing and designing her own yearbook spreads,...