Albert Camus: The Absurdist Mastermind of the Twentieth Century

A French philosopher, novelist, and world-renowned journalist, Albert Camus was one of the most influential writers in the history of literature.

Studio Harcourt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Here is a studio headshot of Albert Camus, taken in 1945.

If life is a cycle just like every other in our knowledge, then is it not our responsibility to break free from it? Is existence a pursuit of happiness or is it an entirely arbitrary sequence of events unfolding with every passing moment? Do those moments mean anything to you? If not, then are you obligated to actively seek an underlying meaning within them? And what will be left of you once you find that your pursuit of a deeper meaning was ultimately futile?

Albert Camus was born on November 7th, 1913 to a working-class family in French Algeria. His father had been killed in World War I during the battle of Marne before Camus was even a year old. As he grew older, Camus became conscious of the poverty surrounding him and the identity he held as a French citizen born in the company of Berber and Arab Algerians. Both of these groups were actively discriminated against at the time. He would go on to describe these early formative years in a collection of essays titled “L’Envers et l’endroit” (1937; “The Wrong Side and the Right Side”).

These publications articulated how Albert discovered that the natural beauty of the physical world is of service to all, regardless of our social strata and personal upbringings.

Camus enrolled into the University of Algiers as a young adult, where his interests in philosophy were fostered by his teacher, John Grenier. While he found substantial success in his thesis works and other small creative constructions, his university career was cut short as a result of his tuberculosis.

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, Camus became a member of the Algerian Communist Party (PCA), which was originally an extension of the French Communist Party before it seceded in 1936. He had been influenced by many left-wing writers and literary figures whose works expressed anticapitalistic sentiments. These intellectuals were primarily concerned with Algerian affairs, however, and didn’t often hold heavily radical views.

During this time he also adapted, directed, and acted for the Workers’ Theatre (Théâtre du Travail). The goal of this organization was to allow working-class citizens and impoverished groups of people to indulge in well-made, meaningful productions of theater.

Camus then began his work as a journalist for the Alger-Républicain, where he began as a book reviewer who would publish personal articles which bridged the gap between fiction and the state of the human condition. By linking the works of authors such as Jean-Paul Sartre to the humanitarian crises which went undiscussed at the time, he simultaneously took his stand on the issues plaguing society whilst also keeping his readers entertained and informed.

His position as an independent thinker and humanitarian would be highlighted during his time as an editor for ‘Combat,’ where he maintained his beliefs based on the core principle that every political system and action needs to be derived from a basis of morality. In other words, regardless of the policies and focal points of a political branch, its true purpose should always be to abide by the generally held concept of what is “right” in its given society. Capital and control should never take precedence over ethics and rectitude. This belief in the human conception of “good” and the values which encapsulate the human condition would be vital to the synthesis of one of his most influential and defining works.

‘The Myth of Sisyphus’ is a lengthy philosophical essay published in 1942, written by Camus during the fall of France. The work was influenced by philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer, delving into the concept of the “absurd.”

Absurd as a philosophical concept does not hold the same definition as it does when used in day-to-day conversation. In philosophy, it is the belief that life possesses no deeper meaning than what is presented on the surface level. There is no hidden idea or “meaning of life,” and existence as a whole is entirely incomprehensible when approached with the human tendency to utilize complex reasoning.

Absurdism has its earliest origins in the works of Søren Kierkegaard, another major influence in the development of ‘The Myth of Sisyphus.’

At first glance, Absurdism may appear simply as a pessimistic and cynical outlook, promoting the crises and existential concerns that plague people of all different identities and beliefs. However, as Guy Bloom ’23 stated, “absurdism as a movement differs from other movements because it accepts life as it is instead of proposing specific endpoints.”

Camus uses this concept to explain how action supersedes contemplation due to the fatuous nature of life itself. There are those who wither at the realization of an absurd existence and those who embrace absurdity in order to live life to its absolute fullest.

The essay is divided into 4 chapters; each of which serves to answer a pressing question regarding the human condition and the experience of an absurd reality.

Chapter 1

The essay starts by discussing the cognizance of just how absurd and senseless life truly is. This chapter concludes with the sentiment that it is impossible to permanently accept a state of absurdity, and that once we abandon our attachment to the pursuit of life’s “purpose” and embrace the offerings of our own existences as they are, we would attain a greater sense of freedom, nothing less and nothing more.

Chapter 2

Camus then goes on to question how an individual who is conscious of their absurd existence should then proceed with their life. Simply put, life will continue without any ethics or social restrictions. The absurd life is one without moderation or moral dilemmas resulting from a lack of control; ultimately, trying to keep the passions of your life at bay is entirely futile.

Camus explains how both a seducer and a conqueror of lands embrace the absurdity of life in order to prosper. The seducer understands that life and love are equivalently temporary, and so he permits himself to bathe in the sin of lust. The conqueror understands that life exists simply as it is, with nothing beyond or underlying. In acceptance of this idea, he burns his legacy into the Earth as it is the most he can do for himself in his nonpermanent reality.

Chapter 3

The role of an absurd artist is then analyzed. Camus asserts that the uninterpretable nature of our lives is what gives art the power to speak to its audience, the absurd spectators. Art, especially of an absurd nature, is a reflection of an incoherent reality. As a result, true absurd art cannot hold even a glimmer of hope or aspiration, as this would serve as an underlying theme in a creation that is meant to be as meaningless as the existence that it reflects.

Good art simply describes and presents a detail of life as it is. Bad art attempts to derive a deeper meaning from an already incoherent reality.

Chapter 4

In the final chapter, Camus details the actual myth of Sisyphus, who is damned by the gods to roll a stone up the side of a mountain, only for it to fall back down once it reaches its peak.

Camus compares this meaningless toil to the life of the average working man, with both figures being doomed to repeat the same pointless tasks with no feasible end in sight. However, the damnation is only apparent if the working man interprets it as mere “toil.”

Albert Camus proposes the idea that Sisyphus is entirely conscious of his fate and the endless nature of his task. Perhaps he starts anew with every instance of failure because he has accepted his fate. It’s not that he’s found any meaning within the stone or the mountain, but that he’s accepted them as they are. In that state of acceptance, Sisyphus has made peace with his life and begins to roll once again.

“The Myth of Sisyphus” is far from Albert Camus’ most popular work. “The Stranger,” “The Plague,” and “The Fall” are much more widely discussed when considering Camus. However, the way it provides such an odd and harmonious interpretation of the “absurdity” of life is a perfect reflection of who Camus was as a writer and as a philosopher.

He doesn’t present the possible meaninglessness of our lives as some impending doom or inescapable fate. Instead, he interprets its realization to be a provider of internal peace. We can’t escape the absurd, so we should simply embrace it during the time we have left.

After World War II, Camus would express sentiments of anti-communism, and advocated strongly for libertarian socialism. The divide between Albert Camus and Marxist ideology would only grow deeper during the Algerian war, as Camus could not envision a fully independent Algeria.

In 1957, 12 years after the end of World War II, Albert Camus was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. At 44 years old, he was the second youngest recipient to ever receive the prize,

He would go on to use the money from his prize to finance the production of one final play, entitled “Demons,” which was an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s novel of the same name.

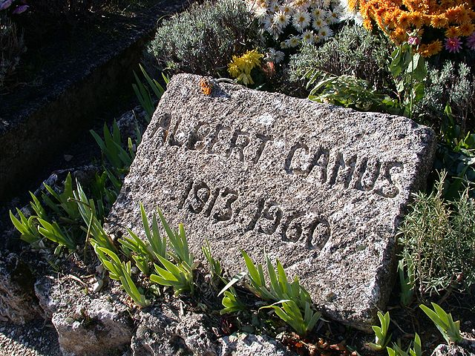

On January 4, 1960, Albert Camus died in a car accident near Sens, in Le Grand Fossard in Villeblevin at the age of 46.

His work has influenced many modern-day artists and writers, such as Chuck Palahniuk, Charles Bukowski, and Samuel Beckett. His depiction of the human condition and his perception of life created ripples in the world of literature, which are still felt to this very day.

And if there is no profound underlying meaning to our lives, perhaps it would be best to embrace these passing moments for what they are instead of losing ourselves in the pursuit of something that simply isn’t there.

The seducer understands that life and love are equivalently temporary, and so he permits himself to bathe in the sin of lust. The conqueror understands that life exists simply as it is, with nothing beyond or underlying. In acceptance of this idea, he burns his legacy into the Earth as it is the most he can do for himself in his nonpermanent reality.

Aaqib Gondal is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey,' where he is responsible for the review and revision of different pieces written by his classmates....