A Conversation With Arthur Frajer

The story of an extraordinary man — who also happens to be my downstairs neighbor.

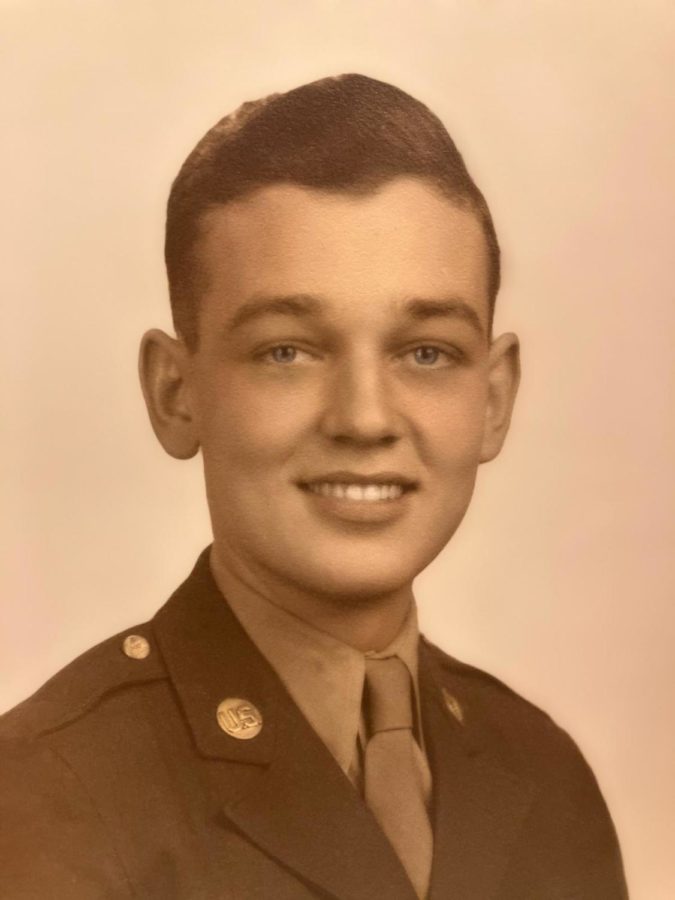

This is Mr. Frajer’s basic training headshot, taken when he was 18.

My downstairs neighbor Arthur Frajer is an extraordinary person. He has lived in our building for well over 30 years, yet we only started saying hello several years ago. From a conversation that my mom had with him one day, I overheard a bit about his life: he’s a veteran, and he is Jewish and originally from Germany. I was very interested in hearing the rest of his remarkable story, and, fortunately, he agreed to an interview.

I had the privilege of interviewing Mr. Frajer in person. Below is the transcript of our interview, which I have edited for clarity. I have also included some additional information, at various points, about places and events that he references.

Tell me a little bit about yourself.

I was born in Germany, I was raised in Germany, and went to school in Germany. If you’re asking about citizenship, that’s a complicated question. I’m not German… this is something different from the U.S. You are whatever your parents are no matter if you’re born [somewhere else]…in those days at least. So my father came from Russia, I was considered Russian even though I don’t know anything about that. […] When we left I was ten years old. So I have a lotta memories, and yes I am Jewish… Hitler came to power in 1933; we left illegally through the border in 1934. I lived in Cologne, Germany, which was a major city and the anti-Semitism started right away but got worse and worse – but the worst of it I did not see, thank God. Thank God to my parents that they had the foresight to leave and get out of there.

So, between 1933 and 1934, what did you experience?

I went to a Jewish school, so this was – in many European countries – not anti-Semitic. It was in many Jewish communities, and generally speaking, Jews went to Jewish schools. 1934, I was ten years old, I did not know we were going to escape because my parents didn’t want anyone to know, so we just went out illegally. What I mean by illegally is that they [the Nazi party] didn’t want you in, but they didn’t want to let you out, either. So we smuggled ourselves out and over the border into Belgium. And they accepted us, on the condition that we leave sooner or later. So I know a lot about what happened, I know the history of it, but I didn’t take part of it. The only thing I can tell you is that what happened to me and my sister – my older sister – is that we messed up a lot of our schooling. When we came across the border into Belgium, they didn’t speak German, they spoke French in there. So personally, I was set back lower than I should have been because you come into a strange country and you want to go to school but you don’t speak the language… it was a big problem.

Not many families tried to emigrate until much later.

First of all, German Jews didn’t leave because they didn’t believe this was going to go further. Being [that] my father was not from Germany, he was a Russian Jew, many of them went to Germany and other countries so he was an immigrant himself actually…

I went and stayed in Belgium a year and a half or something like that, I went to school there, I didn’t speak their language, very difficult as a child… but, oh, you can adapt…

[…]

Either you had to be smuggled out illegally, or you had – what they did those days was they didn’t want you in and they didn’t want you out… if you wanted to leave legally, you had to pay a huge tax which we didn’t want to. We didn’t do that. And we never came back, and it’s just a little interesting fact that when we left Germany, and went to Belgium, and lived for a while in a hotel, I remember, from the Gestapo, they sent us a registered letter that said we left illegally, we owed so and so much, and if we ever came back and set foot on the German territory we would be immediately arrested. Oh, they knew what happened.

Do you remember any obvious antisemitism in 1933 or 1934, before you left?

It started before ’33, right, politics-wise – this is well known – Hitler actually got elected. This was not a takeover: he won the election, and he blamed all the problems of Germany […] he said Jews were responsible for all of that, and he got elected on that basis. Germany had economic problems, and he blamed the Jews, basically. And that’s how this whole thing got started. I think – that’s my opinion – that they [German citizens] voted for him because of that. Because they had to blame somebody for their own problems…

Do you have any personal memories of it?

I have the memory that when we came out of school, I was a little kid, think 6, 7, 8 years old, there were other kids, Christian kids, making remarks and fun of us, “oh, here come the Jews, the Jews.” But there was no… you hear about the concentration camps. That came later, not when I was there.

When you were going to Belgium, do you remember being confused at all?

What was stunning to me is that my father chose not to tell us. He said we were going on vacation, then he said we’re never going back, and I said “Gee, I didn’t say goodbye to all my little friends…” so that’s the story on that.

[…]

Don’t forget I was ten years old when we left. But it stays in your memory.

I know when you were eighteen, you got conscripted to go fight. Can you also tell me about that?

I came to the United States in 1937. It was very bad times here. I was thirteen. And the same problem again! I had to go to school and I didn’t speak a word of English. What hurt me the most, personally, is that I lost out on schooling, and for the rest of my life, I was always put down, I was always with much younger kids because I didn’t speak the language.

Do you remember, as you were growing up, as a teenager in the United States, hearing about what was happening in Germany?

Of course. We had many loved people that came after us, relatives and friends, that came here later than we did. Most of the Jewish population that came to the US was more like in 1938, 1939. We came in ’37. So we were amongst the early ones. I was very confused, because of language… I could speak French by the time we came here. Actually, I speak three languages. I speak German, I speak French, and I speak English. I still do.

***

In the mid-to-late 1930s, many families like Mr. Frajer’s read the writing on the wall and fled Germany. In fact, in light of the Nazi Party takeover, an estimated 37,000-38,000 people emigrated, predominantly to nearby countries like France, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Belgium. Later on, some of these countries – Belgium included – abetted the Gestapo in their attempts to hunt down German-Jewish immigrants and refugees, and, of course, many of those countries were invaded by Germany in 1940. Many of the people that settled there were forced to return to Germany. Others, like Mr. Frajer’s family, continued on to the United States, Palestine, Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, and China – most notably Shanghai. By 1939, approximately 282,000 Jews had left Germany.

***

Very impressive! So, as you were growing up here, as a teenager–

I was thirteen years old, I became bar miztvah’d, and I had my bar mitzvah here, in New York.

Between when you came to the United States and when you got drafted–

I went to DeWitt Clinton high school (here we spoke about DeWitt Clinton being right next to Bronx Science).

I did not go to college. I had to go make a living… today is different. But life has been good to me here. Don’t forget we came in the 1930s and there were enormous problems in the United States. There are big problems now too! (laughs)

So, when you were 18 and you went to fight, what was that like – can you tell me a little bit more about that?

In those days, they drafted you from age 18, and I was 18 and very young. Not a mature 18-year-old. Worst of all was, in my opinion, was – I was not a citizen, but a permanent resident. If you were a permanent resident, the U.S. law was that you had to go to the military. So I became a citizen when I was drafted. Three months later – and there were a lot of ’em like me – they took us to court, and I became a citizen. I had a rough time in the military because I was from the youngest – there are very few today, veterans, from the second world war – you’d have to be, I’d say, at least 90 minimum. So I had a rough time, if you want to know. I was shocked about a lot of things. I was shocked about the blacks being divided from whites, in the army, in the U.S.; it was a big big surprise to me because in New York we didn’t have that. Being I spoke German, I got a little bit of a break in my opinion. I went to military intelligence school and they used me as an interpreter. I went in the army in 1943, and D-day was 1944. So I was amongst the first. I was in Normandy.

On D-day?

No, no, on D+3 day – there’s a difference. The ones on D-day, they got hit bad. But I was the next contingent, and we went three days later. and I went to school here through Camp Ritchie in Maryland, to learn what entails being an interrogator and a translator. So I was promoted to a corporal almost right away, so it was a big deal in those days, and I was particularly young-looking, so everyone thought I was a volunteer, which I wasn’t. You could volunteer at 17. So I was not there on D-day – there were enormous casualties – so I came in on the third day, in this enormous landing vessel, and was stationed in – Cherbourg was the biggest port, I remember now, a French port – and we were gonna settle down in Cherbourg. It was liberated. So I stayed in Cherbourg, France, for a while… I was among the lucky ones – I was not injured – and it was shocking when we landed we saw still all the bodies laying there. I was not in an incumbent troop, I was in military intelligence, so I was at a little bit of an advantage. I spoke French and I spoke German.

***

Camp Ritchie, in Maryland, was a military intelligence-focused camp that trained about 20,000 interrogators and intelligence-gatherers over the course of World War II (dubbed “Ritchie Boys”). Of these 20,000 men, approximately 2,000 were Austrian- and German-Jewish refugees to the United States, who then turned around and used their knowledge of German customs to enhance their work. It is thought that of all the military intelligence that the American army gathered during the war, upwards of sixty percent of the actionable intelligence – or that which was usable – was acquired by Ritchie Boys. These men were dispatched to all the different fronts that the war was fought on, from Europe to Asia to North Africa. If you want to read more about the Ritchie Boys, click here or here.

***

It must have been helpful to know French!

Yes. We were stationed in Paris for a while, and like I said, I was really not destined to be a combat soldier, which really was an advantage. I was not getting hurt, I was just about turning 19. […] You get to be a man in the army. I came in in June ’43; I was dismissed in January ’46 after everything was finished.

Did you ever go to Germany?

Yes! I was in Berlin! There was a lot going on. I was in France, Paris, then I wound up in Berlin with the Russian troops.

Did you visit Cologne while you were in Germany?

Well, I did go to Cologne, but not then. What happened after the war – and this went on ‘til fairly recently – what happened was the city of Cologne invited us to show how things have changed and so on, but I did go back but not while I was in the army. And we stayed in Berlin, and we had headquarters in Berlin.

Did you translate and interrogate in Berlin?

I had never seen Berlin before. Everything was destroyed. But yes, to a lesser extent. The war was going to an end. And then, I came home, I was 21, 22, I got an honorable discharge. As a veteran I will say this to you: World War II veterans were not compensated, were not thought of later on for any benefits. Today is totally different. I applied once to the Veterans Association for medical help and they refused me saying there’s not funds for World War II veterans. It’s changed now. And to tell you the truth, I also removed myself totally from everything. I didn’t join the VA, or the Vets for Wars, all these vet organizations. And I don’t know how many of us are still alive, but there’s few. There’s few. And as I said you have to be in your mid 90s – the war was over in ’45 – so you can just figure. There’s less and less of us. I’m sort of blessed in a way; in a way it’s not easy. I’m 98 years old and I do everything myself. I don’t want to go see any old age institutions and all that. So that’s my story.

Update: Arthur Frajer passed away on Friday, January 26th, 2024 at the age of 99 years and 2 months. May he rest in peace.

“I’m sort of blessed in a way; in a way it’s not easy.”

Felicia Jennings-Brown is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ What she appreciates the most about journalistic writing is its use as a channel to...