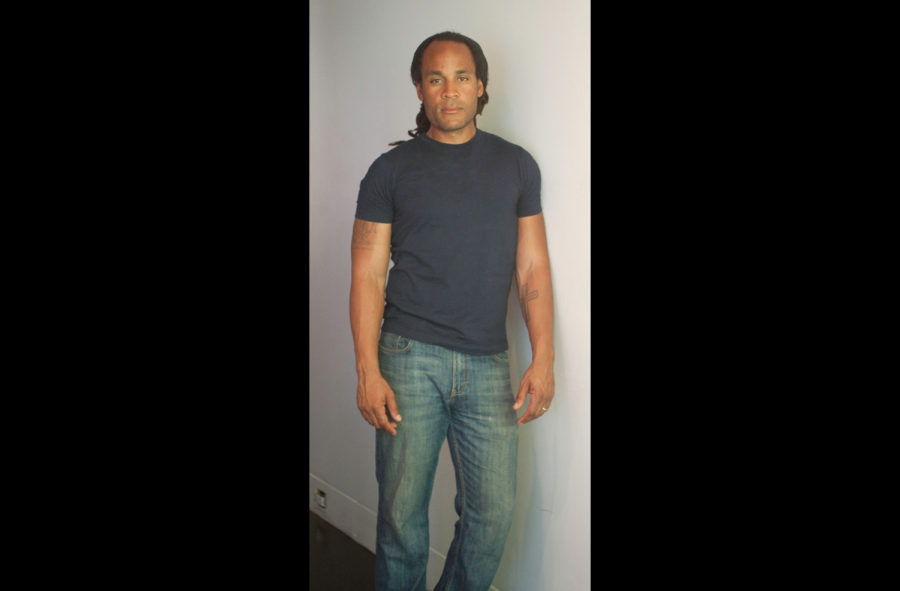

An Existentialist Enigma: A Profile of the Novelist Michael Thomas

He is known for being a Dublin International Literary Award winner, and an author and professor. In our conversation, we discussed a myriad of topics.

Ben Russell, Photo used by permission of Grove Atlantic, Inc.

Michael Thomas has nine bestselling novels, several of which are financial thrillers based on his own lived experiences.

“I know I’m not doing well.” Michael Thomas begins Man Gone Down, his novel about an African American man with an estranged white wife who is forced to produce a sum of money to get his children returned to him. With commentary on the American dream, he intertwines his own life experiences into the novel. The 431-page book explores themes of race, mortality, wealth, kindness, self-preservation, and even capitalism.

Though the book won him the Dublin International Literary Award, Michael Thomas is much more than a novelist.

Thomas was born and raised in Boston, which he references multiple times in his novels. A component that makes Thomas’ feats especially impressive is that he was diagnosed with multiple disabilities in his early childhood; these include dyslexia, synesthesia, and Asperger’s. Developing as a neurodivergent child in late 20th century America was a constitutive and formative experience, shifting and altering his perspectives.

In conjunction with these hardships, Thomas cites being raised poor and African American in Boston as a major formative aspect of his early upbringing and current character as well. These fiscal focuses have had a significant impact on the socio-economic issues in his life, featured as significant subjects in two of his books, Man Gone Down and The Broken King.

Even with his early educational and developmental obstacles, Thomas received his B.A. from Hunter College, where he currently teaches, and his M.F.A. from Warren Wilson College. Throughout his academic career, Thomas attended over four different institutions before graduating with an undergraduate degree.

Thomas is truly unique, and this quality seeps into his writing and process. In an interview, Thomas said, “‘I kind of wrote [Man Gone Down] in a fit …I had a bunch of jobs. I was teaching four classes a semester and two or three in the summer, working construction and coaching soccer and baseball, and trying to build my house. I don’t think it is something I could replicate.’”

Thomas’s writing style is commonly described as impactful, thought-invoking, dark, with “unsentimental clarity.” Not unlike conversations with him himself, his books elicit notions of philosophical and existential conflicts.

Below are some of the questions and answers from an hour-long interview that I conducted with Thomas over Zoom, where he expresses similar sentiments:

Interviewer: Who or what do you draw inspiration from, in general and in your personal and professional life?

Thomas: I don’t know if we draw inspiration. Sometimes I get encouragement from other people, places, and things, typically from what I read or listen to, or on a run or a workout or walk or game with my kids. So I think that place of inspiration, if that’s what I could call it, is always there, just being reminded that it’s there, reminding me that I’m supposed to be doing something or reminded that I want to do something. So there’s no seeking. There are the texts, the words, the literature, the films, and the historical people who’ve come before and are working now, they’re always there. So memory, getting nudged.

Interviewer: How would you say your upbringing impacted you and your writing and your character overall?

Thomas: I’m still figuring that out. Because my life didn’t end there and the perspective I had on that which came before was limited. So decisions I’ve made about my upbringing, my parents, and my influences in my 20’s, 30’s, and 40’s, have changed. But some things are the same. I came from a really beautiful and strange and frightening and dynamic place. I think I still inhabit that place. My parents were very different people, who I think the narrator [in Man Gone Down] talks about; his parents should not have been together. He cannot understand who or what it was that brought them together.

I think, for me, artistically, intellectually, politically, and socially, I was just born at a particular time and convergence in the United States and in the world. The first generation of immigrants in America. My mom’s from the Jim Crow South, my dad’s from the urban north, my dad was highly educated, but my mom was not so much. My mom experienced the Klan, my dad experienced Quaker Abolitionists. My dad grew up in an integrated northern neighborhood. His father was a college graduate, he was a college graduate. Didn’t do much with it … My mom did not receive a college education. But my mom was the one who was around and who stayed. So we do not have a particular inheritance of DuBois in the talented 10th. But the more I think about it, you can picture a neurodivergent kid … who lived in a pretty wide society in the neighborhood in which my childhood neighborhood was integrated. And black Southern families and northern Black families, white indigenous peoples, everyone.

So in some ways, they thought that was America, the Vietnam war was going on. Boston was in a deep recession. King had only been assassinated a few years before I really came into consciousness. And I was born in ’67. He was assassinated in ’68. The Boston Public School System imploded in the first grade. And it’s the things that I think are not taken for granted today. But there was no occupational therapy in the ’70s for a dyslexic again, a neurodivergent kid who could read at three but couldn’t tie his shoes until 10. It was a strange world. And it was also the kind you’re experiencing maybe now. The pall of the ’70s, Vietnam, assassinations, the dream of the ’60s, and the work of the ’60s. And what came after that was not only a financial depression but still physical, maybe even a spiritual absence. That was perhaps no longer not everywhere, obviously. But of course, this is in hindsight. But really coming of age in the ’70s, in the age of Reagan when I was in high school, nuclear warfare and duck and cover.

Again, integration, I was that black kid in the hallway to school, or at the dance. I don’t know if that’s going to be replicated. And also my father, the books he gave me, the films. Because I learned to process the world through those to try and figure out what’s going on in your head and in 1974, through like, Greek mythology, or Homer, to make sense of the world around us, or through Curtis Mayfield or Stevie Wonder or Marvin Gaye or all of it at once or the Red Sox?

Interviewer: If you had to recommend three pieces of literature to anybody of any age, what would they be?

Thomas: I think it depends on the context of that person. Because you know, the right or the wrong book at the right or the wrong time can really mold somebody. So it depends on where they are and what I think they might need, you know, what would provide companionship and gentle guidance. I don’t like creating hierarchies but I think perhaps the two most important documents of the 20th century and thereby the 21st to me are “Letters from Birmingham Jail” and Baldwin’s “Fire Next Time.” … I think that’s something everyone should read. But I don’t think I’d give that to a seven-year-old. I would offer Invisible Man to some people. I would offer Their Eyes Were Watching God to some people, I would offer Audrey Lorde’s Sister Outsider… Eliot’s Four Quartets really speaks, again, depending on the person. I think some people might even be too old, for certain texts, and too rigid. I’d offer The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to some people, but not just books, right? It’s music, too. I teach Literature and Creative Writing. And so much of your experience, I’m sure with literature, and your education is a tiered system of education.

*********

During this part of the interview, Thomas discusses literature on a continuum, in conjunction with and in relation to other media. He stresses the importance of consuming a diverse taste of influences, ranging from literary classics to modern pop music.

*********

Interviewer: What is an issue that you think is overlooked?

Thomas: Sometimes I forget I’m a person in the world who has an impact and who is impacted. Who isn’t, you know, floating or in some cave and forgotten. That’s one. And that things I say, I’m trying not to be sardonic or dark, especially on young people and I understand that it has a political impact on people, social-political impact… I might be a hard case and might have grown up not respecting prison authority, but I do remember missing guidance and so undercutting my own guidance or authority to people who are perhaps looking for help is perhaps shirking responsibility or societal responsibility to other people holding this up, somebody’s great thoughts… That kind of constant modulating and deflecting, it’s a coping mechanism.

I think politically, really just the impact, educate more policies, monetary policies. I think apathy. In “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King talks about the people he is most disappointed with and that’s really centrist white people, moderate for the people in America. That was almost 60 years ago … And today, it was walking. Subways were blocked up and there was a woman toddler and a stroller, a preschooler walking next to them and they got in a fistfight. And when did bring it up? Standing in Washington pretending not to see what’s going on. Do you respond to that? To other people?

I think part of the pop psychology of today is this abdication of responsibility for other people and to other people. And to alter truism. And I am responsible doesn’t mean I can control somebody’s life. But you have to help people. You know, just queuing up for the elevator, or the escalator, or the subway, it’s just manners, I think, are important. Just think about somebody other than yourself. I think that’s part of everyday political reality. I think understanding what privilege is, I think understanding the difference between fear and danger. I think, again, announcing the reality of other people. I think this kind of talk, right? Apathy and talk about Roe v. Wade. We could see this coming for years. Trump’s election, we could see this coming for years. The death of Floyd, this has been happening over and over again. For years other people have experienced it, other people watched it.

Other people have been suffering and most people suffer. And it’s not an epiphany to most people. So I think getting back to King, self-purification. Just admitting you don’t know, you don’t have an answer and there’s a reason why. Your opinion might not matter. But you do have to weigh in and to weigh in, you have to start asking and it is on you to learn… I think you have to practice being a political and social being all of the time and just trying to do the right thing. And until you have cultural literacy, you can’t do it.

Interviewer: Do you think that’s a thing that society needs to address as a whole, educating the population? Or do you think that’s an individual choice that we all need to make?

Thomas: I think it’s both. When people talk about philosophy, some believe that philosophy is something you have perhaps learned or experienced, and then you keep, rather than the love of knowledge, the etymology of the word, right, the word of wisdom, searching for truth and so constantly challenging one’s notions, you know, is this truth, is this an attitude, all the totems, and taboos I have… Fire Next Times, one has to be tough and philosophical, but not philosophically tough other than that, you have to be willing to challenge your assumptions. You always have to be willing to be dynamic in your own mind.

Now, educationally, how do you do that when you have a classroom in a public school in New York City with 34 kids? Few resources, and maybe special needs kids and kids who didn’t have breakfast, and who might not be getting dinner? And a special gifted and talented program. Who begins that conversation? What about a curriculum? Why are you teaching a seven-year-old STEM? I don’t know. Where do we begin that conversation?

So my youngest is right now, in public school, and my three adult children, only in private school. So I’m watching them trying to teach him, to write words, but also penmanship, which talking with his mom is fraught. Because he’s thinking about the quality of the letter, and whether or not he’s written well, rather than the quality of the word as to what it means, its nuances, or the quality of the sound of the word. Thinking about the wrong things, that’s not learning? That’s some kind of fine motor skill that needs to be developed, obviously, but which one do you give privilege? I think pedagogical models are fraught, largely. And I think largely tied to pedagogical models, certainly, city public schools are fraught, because again, resources. Who’s doing the teaching? Who’s the superintendent? What is the life of the mind if you’re driven towards testing and regents, then you’re not thinking about quality.

You can have any euphemism like school for excellence… I think this is a while ago, 34% of New York’s public school children receive 30% of New York’s state budget, there’s something horribly wrong there, especially when the infrastructure of the school system is shot. What are you doing for your kids? What are you doing for your teachers? You can’t give a teacher 34 students in a crowded classroom. And you can’t test in third grade, to determine what their middle school is going to be at seven or eight.

So nuance, quality of thought, depth, depth of thought, rather than just drilling and reciting and the absorption and the articulation of internalized knowledge is important, but it’s not a beginning or is it the end of education. So the educational system is living off platitudes and euphemisms of cliché, empty statements. What is the quality of education?

Your generation is going to have to be deeply educated in the humanities and the generations to come. So that if you do get an MBA, and go to work in corporate America, you might have a conscience.

Interviewer: Do you think that’s an issue with pushing STEM because, in recent decades, STEM has been pushed? Do you think not pushing enough of this critical thinking in curriculums is an issue?

Thomas: Except for the unique person, if you are a data engineer, or a data collector, or a computer scientist, or building turbines somewhere, until you understand what it is to be humane, and practice what it is to be humane for whom you’re building these things. For people. Why are you researching the cures for these diseases? It is for people, for various reasons, there are real people suffering. What are you going to do with this technology?

So if you do have a STEM education, and you do come up with Amazon as your idea, then what constant training have you had since you were a kid that then demands in you to ask the question, what do I do with all this money? These are just basic ethical questions without excuses or justifications as to why you get what you get.

*********

Thomas is able to evoke introspective and reflective topics in both his writing and in plain conversation. He is the pinnacle of success amidst struggle, with the ability to confess and obtain the self-awareness that he and every single person has a wealth of room for personal growth.

“I think that’s part of everyday political reality. I think understanding what privilege is, I think understanding the difference between fear and danger. I think, again, announcing the reality of other people,” said Michael Thomas.

Donna Celentano is an Editor-in-Chief for 'The Science Survey.' As an Editor-in-Chief, she helps manage her peers’ work, providing helpful and informed...