The Long-Empty 1930s ‘Metro Theater’ is Returning to the Upper West Side

A gem of the Upper West Side, the Art-Deco style Metro Theater is forecasted to reopen in 2023, 17 years after it last closed.

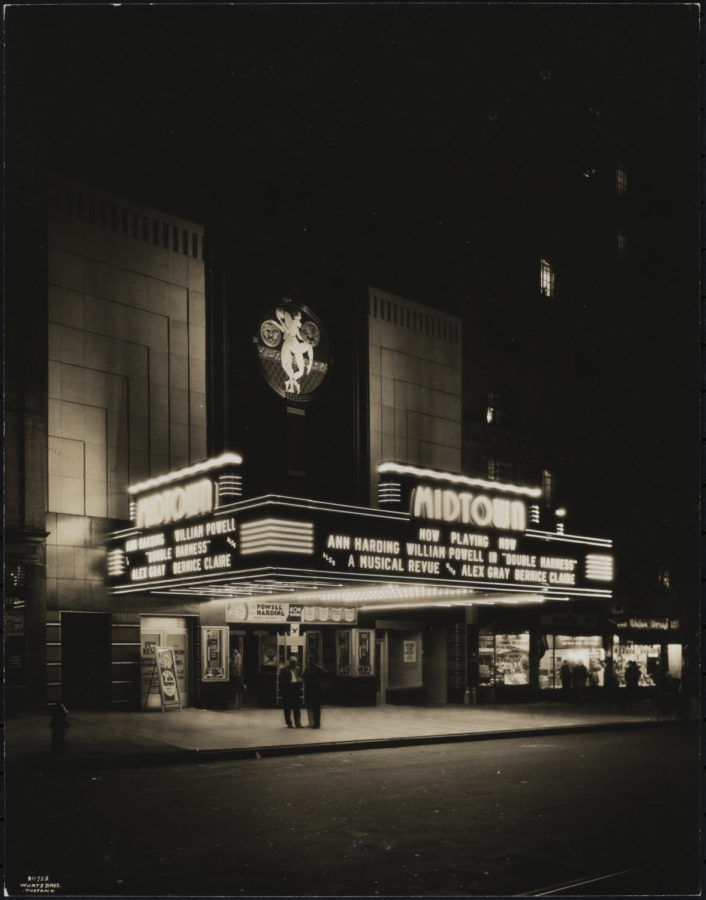

Wurts Bros. / Used by permission of the Museum of the City of New York

Here is the Midtown Theater shortly after it opened in 1933. Its grand terracotta facade and marquee still stand today, although with a few new additions and a new name: The Metro Theater.

In a rapidly developing city, it can be hard to find remnants of New York’s history. Surrounded by unassuming apartment buildings, however, is an antiquity that reminds all passers-by of what once was a center for artistic activity and entertainment.

Spanning 10,260 square feet, the Metro Theater is located on Broadway between 99th and 100th Streets in Manhattan. The historic movie theater boasts unique art-deco architecture that stands out as a relic in the city’s current skyline of eye-boggling glass buildings.

“It’s in a neighborhood that is made up of pretty mainstream stores, so it’s interesting to see the stark contrast between the old theater and the current buildings,” said Andrew Morrissey ’23.

The idea for the theater was conceived in 1931, when architects Russel Boak and Hyman Paris began sketching designs for a building incorporating elements of two architectural styles: Art Deco and Moderne. According to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, its Art Deco elements are seen in its “vertical accents, use of polychromatic terra cotta, the simple geometric pattern of the upper facade, and central terra-cotta medallion featuring stylized forms.” The Moderne elements of the theater’s architecture are featured in its “application of horizontal lines, as seen in the chrome-striped, elongated marquee, the use of streamlined curves, and the flat patterned surface of the upper facade.”

On the outside, a fifty-foot wide facade and metal marquee hang, looming over the east side of Broadway. The marquee itself has been there since 1933, though rows of small light bulbs have been added along the top and bottom. Written in the marquee is “Metro” in neon red Deco style letters. A polychromed medallion of the faces of comedy and tragedy is featured on a terra cotta wall above the marquee – the theater’s most distinctive feature.

The glazed medallion is set in an aluminum frame in the center of the black and maroon display. It contains two stylized figures holding theatrical masks that represent comedy and tragedy. Behind the medallion, the terra cotta is lavender and there is a section of checkered print. The two are separated by a yellow floral band.

Given that it is a small neighborhood movie theater, the Metro is one of the last of its kind. Throughout the 1920s, large movie “palaces” sprung up to become the dominant source of American entertainment after the first soundtrack breakthrough movie, The Jazz Singer, opened in the States. The architecture of the American movie theater developed with the rising popularity of movies: both small and large theaters lined the streets of major cities. Theaters in the 1920s were designed to look exotic and seat thousands of people.

As the Great Depression hit, however, the large movie palaces that characterized the previous decades became impractical and the only new theaters being built were smaller and made to seat only 500 to 1,000 people. The Midtown (now Metro) Theater fit this mold exactly. All theaters erected during this time period reflected, in the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s words, modernistic design and “simplicity of material and ornament.” What makes the Metro Theater different though, is its idiosyncratic terra cotta facade.

After the theater’s closure, its ornately embellished interior full of Art Deco character was completely gutted. Where there was once a golden ceiling with moldings of floral bouquets, there is bare concrete. The corners where sylph statues once stood are empty. Although this loss of historical charm is devastating to some, as Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine told The New York Times in 2015 “at least it isn’t a Duane Reade.”

In its decades of life, the Metro Theater has featured a variety of movie genres. Originally showing first-run films when it first opened, the theater switched to international and arthouse films by directors such as Jean-Luc Goddard, Louis Buñuel, and Roman Polanski in the 1950s and continued showing these until the 1960s. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, the theater exclusively played mature films. In 1982, Daniel Talbot bought the theater, re-named it the Metro Theater, and began showing first-run films once again.

After providing the Upper West Side with cinematic entertainment for 72 years, the Metro Theater closed in 2005.

Since they have gotten the hopes of New Yorkers up many times with premature promises of renovation, native Upper West Siders are skeptical of the news of Metro Theater’s reopening. Over the past two decades, headlines in The New York Times chronicling the fate of the Metro Theater have reappeared again and again. Titles such as “What to Make of the Metro Theater”, “Landmark Metro Theater in Manhattan Will be Reborn as a Planet Fitness”, or “From Metro Theater to Urban Outfitters” gave Upper West Side locals hope that the building would be reborn, only for their hopes to be dashed as no renovation was made.

The current anonymous buyer planned for skepticism though, and met with Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine to prove to locals that this sale was legitimate. The new owner hopes to open the building in 2023 as a boutique movie theater where movie-goers can order restaurant food while enjoying a film. This renovation stays true to the theater’s history as an off-beat cinematic destination, which constantly reinvented itself throughout the 20th century.

“I’ve grown up walking past the abandoned Metro Theater, and I’ve always wondered what it would be like if I had been alive while it was still open,” Morrissey said. If all goes well with the plans for the Metro Theater’s renovation, young New Yorkers may soon find out the answer to this question.

This renovation stays true to the theater’s history as an off-beat cinematic destination, which constantly reinvented itself throughout the 20th century.

Helen Stone is the Editor in Chief and Facebook Editor for 'The Science Survey.' She is interested in journalistic writing because she believes that a...