Sappho, Greece’s Forgotten ‘Tenth Muse’

Sappho of Lesbos, once considered a great lyrical poet of antiquity, faded into obscurity in subsequent centuries. However, she has reemerged in popular culture today as a lesbian icon.

John William Godward, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sappho, often considered the tenth muse, was thought of by many scholars to be one of the best lyrical poets of her time. (‘In the Days of Sappho,’ by John William Godward)

In the fall of my ninth-grade year, I stood in the middle of the Bronx Science East gymnasium, holding three textbooks in my arms as I waited in line to swipe them out. As I followed COVID-19 protocols and stood three feet away from the person in front of me, I examined the textbooks that I would check out for the year: an edition of Jenny’s First Year Latin, a literature textbook, and Homer’s The Odyssey.

The Odyssey and The Iliad, both epic poems written by Homer, are considered some of the most important works in Western literature. These texts are taught in high schools, colleges, and universities throughout the United States, giving us an invaluable glimpse into the Ancient Greeks’ cultural disposition and providing philosophical food for thought — namely on fate, freedom, and heroism. Homer is credited for transforming cultural perceptions amongst the Ancient Greeks which have influenced Western ideals ever since. Homer revolutionized the structure of the epic. Homer’s works earn praise from literature teachers all over the world. The famed Athenian philosopher Plato once stated that Homer “educated the Greeks.” For someone who denounced poetry as being immoral and as merely being a copy of the natural world, Plato held Homer in high regard.

However, what if Homer’s works became lost to time? What if all that we could use to piece together his works were through secondhand accounts of his talent and his remaining poetry? For many people, this notion would be difficult to grasp, considering Homer’s influence on modern literature. Yet, this is what happened to Sappho of Lesbos, whose poetry was once thought to be just as important as Homer’s.

Let’s take a step back. Who is Sappho of Lesbos? What, exactly, did she write? And what on earth happened to her poetry?

Sappho was born to a wealthy, possibly aristocratic family on the island of Lesbos sometime in 610 BCE. The earlier parts of Sappho’s life are murky, with only a handful of definite details. What we know of her childhood is relatively new. The Brother’s Poem, excavated in 2014 and translated by Dirk Obbink, introduces us to two of Sappho’s brothers, Kharaxos and Larikhos, with Sappho addressing the poem to an unnamed third party. A third brother, Eurygius, is mentioned by historians, though little is known about him.

Unlike Sappho’s brothers, her parents’ identities and personalities are unresolved. Depending on which historian you read and the text that you are reading, her parents differ wildly from source to source. Sappho’s father has at least ten attributed names, from Scamandronymus to Scamander to Ecrytus. According to Ovid’s Heroides, a collection of fifteen epistolary poems, he died when she was seven, though actual recounts from the poet remain unknown. It’s widely believed that Sappho may have written about her parents in a now-lost poem.

Historians believe that Sappho’s mother is named Cleis, based on the Cleis Poem written by Sappho where she addresses a girl often believed to be her daughter, Cleis. Historians assume that the younger Cleis’s name came from the elder, based on a Greek tradition that has survived since antiquity — calling first and second-born daughters after their grandmothers. However, this evidence has been put under further scrutiny, with the word Cleis also being used to describe slaves, denote younger lovers in same-sex relationships, or to address any young person.

In her adult years, Sappho lived in the city of Mytilene in Lesbos. Although historians believe that she was a priestess of Aphrodite, she is assumed to have run a Thasos, the term used for a group of people who worshiped a shared god. The Thasos was a preparatory school for young girls to educate them on marriage, and they regularly met under her leadership. However, this theory has increasingly drawn criticism from the scholarly world, with classist Holt Parker debunking this perception in his 1993 article ‘Sappho Schoolmistress’, as well as receiving further examination by an academic article published by Claude Calame. The second theory is that the Thasos, in actuality, was a group of women who were similar to each other economically and politically, and engaged in romantic relationships. It’s commonly believed that works such as Sappho 31 or Fragment 94 are poems expressing her relationships with the women believed to have been in her Thiasos.

In queer circles, Sappho has frequently been referred to as the original lesbian; her name is the root in the word Sapphic, a term used to describe lesbian attraction to women. The word lesbian is derived from Sappho’s home island of Lesbos. The term originated in the 1890s during the Victorian Era, recorded in a medical dictionary. The term sapphic also was used in Magnus Hirschfeld’s 1896’s Sappho and Socrates: Or How is the Love of Men and Women for Persons of Their Own Sex Explained? , a pamphlet defending homosexuality. During the 20th century, the term lesbian began to float around various subcultures describing a common identity. The term sapphic was usually synonymous with the term lesbian, and it only began being used as its own separate identity in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Lesbian poets such as Natalie Barney and Renee Vivien seek inspiration from Sappho’s works and they include multiple quotes from her works in their writing.

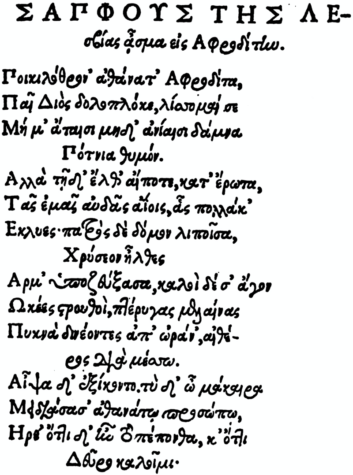

But what made Sappho’s poetry so special in the first place, to the point where she is now “the female Homer?” Unlike various well- regarded male contemporaries of her time, Sappho’s poetry did not consist of epic poems. Instead, Sappho’s poems were far more personal, discussing primarily her relationships with other women, her family, hymns to Aphrodite, and her challenges. For example, in Sappho’s famous ‘Ode to Aphrodite,‘ the poetess calls upon the Goddess of love to help her with romantic prospects. Here, Sappho weaves an image of a heartbroken woman yearning for the object of her affection and so turns to her Goddess for help. This poem uses elegant prose and heavy imagery to draw in the reader. In addition, the poem uses imagery commonly associated with Aphrodite, such as doves. This is a common motif in Sappho’s poetry, where she constantly utilizes the images of doves, flowers, and garlands.

The Goddess herself is someone who, while exasperated by Sappho’s ever-shifting romantic prospects, is also willing to intervene and offer her help. For instance, the lines in which Aphrodite is speaking to Sappho about her newfound love. “She that fain would fly, she shall quickly follow/ She that now rejects, yet with gifts shall woo thee / She that heeds thee not, soon shall love to madness.” Aphrodite begins each line in this stanza by describing how Sappho’s love rejects her advancements before promising that soon, through the help of Aphrodite, the woman will come to love Sappho and return her affections. She describes Aphrodite coming to answer her prayer with surprising swiftness and a smile on her face. The poem likens the Goddess to an old friend of Sappho’s, consoling her and promising better things to come.

Another way that Sappho’s poetry deviates from the then established norm is by using the pronoun ‘I.’ During Sappho’s time, it was commonplace for poets to invoke the Muses — the Greek goddesses who inspired various creative arts — in order to ask them to narrate the tale. Instead of taking this tried-and-true approach, Sappho switched direction and centered herself in the poem, which was a revolutionary approach towards poetry. Sappho turned the themes of her poetry away from the epic tales of heroes and gods and instead focused on more personal, relatable issues. Her personal stories combined with clever wordplay and vivid, evocative descriptions allow audiences to step into her shoes and relate to her in a way that traditional Greek epics do not allow them to.

Sappho performed her poems all over Ancient Greece, inspiring awe wherever she went. Scholars and historians alike praised her poetic genius, with Plato himself even going as far as saying that she was the ‘Tenth Muse.’ She was one of few women commemorated on ceramics at the time. Pottery depicts her standing with a lyre, performing or composing poetry to various audiences. Her life was chronicled — or, attempted to be chronicled — in the Suda, a 10th- century Byzantine encyclopedia of the Mediterranean world. She even created a distinct style of poetry, the Sapphic Verse, an Aeolic verse of four lines. The sapphic Verse is the longest-lasting form of Classical poetry in the West. Even three centuries after her death, there was so much buzz surrounding her that one Greek historian confidently wrote that people would remember her until the end of time.

Despite this, only 650 lines of her believed 10,000 lines of poetry remain publicly known. One theory that used to be commonly accepted was that in 1073, Pope Gregory VII ordered all of Sappho’s poetry to burn due to her extensive homoerotic imagery. This testament, however, does not seem to hold any actual evidence to support it besides a handful of reports from Renaissance scholars whose facts regarding the burnings appeared to change on the fly.

The actual story of how Sappho’s poetry fell into disuse is far more mundane than a horde of angry Church officials punting papyri into holy fires, and in a way, seems to be so much sadder. Sappho wrote her poetry in her native Aeolic dialect, a dialect of Greek that became more difficult to translate as the centuries went by. Then, after Alexander the Great’s conquests, Greece adopted a standard dialect called Koine. Koine speakers would have had a challenging time with Aeolic Greek, and over time it just became too much of a hassle to translate her work. Maybe no one censored it; instead, it just became lost in translation.

“It’s a shame that a lot of Sappho’s poetry is lost. There’s so much of it that we’ll never read. I honestly wish that it was more accessible,” remarked one anonymous student. The two of us talked about Sappho and commiserate over her fade into obscurity. It becomes more sad when you read a line of poetry that she scribbled onto a long-lost poem: “Someone, I tell you, in another time will remember us.”

So what do we truly know about Sappho? Six hundred fifty lines of poetry, some references by historians and philosophers, and a whole lot of blank spaces. No matter how far we dig into Sappho’s life, we emerge with more questions and fewer answers than what we started with.

To read poet Anne Carson’s acclaimed translation of Sappho’s poetry, If Not Winter: Fragments of Sappho, click HERE.

Let’s take a step back. Who is Sappho of Lesbos? What, exactly, did she write? And what on earth happened to her poetry?

Nehla Chowdhury is an Editor-in-Chief for 'The Science Survey,' as well as a Social Media Editor. Nehla enjoys researching topics for their articles, as...