Where 2+2 = 5: Orwell’s Oracular Opuses Are Not Outdated

From 1903, to ‘1984,’ to 2021, Orwell’s criticism of the socioeconomic fabric around him rings true today.

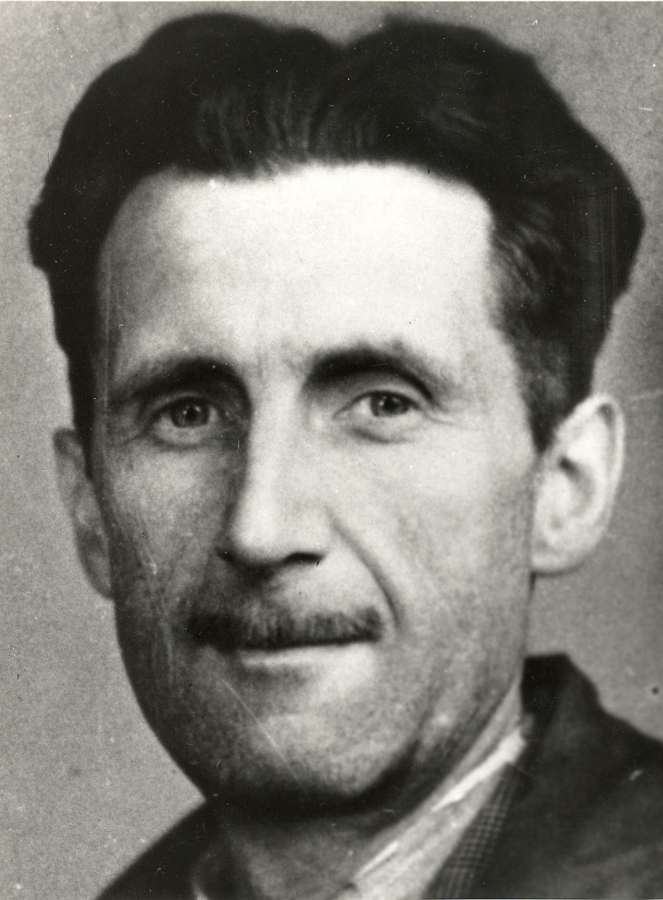

Pictured is Eric Arthur Blair at forty years old, better known under his pseudonym, George Orwell.

Renowned for his artful use of words, George Orwell’s first utterance is reflective of his view on mankind: “beastly.”

Born in 1903 to a British official and the daughter of an unsuccessful teak merchant, Orwell was brought up as his true name: Eric Arthur Blair. It was not until he published his novel ‘Down and Out in Paris and London’ that the pseudonym George Orwell — chosen after the River Orwell in East Anglia — was established. Ashamed that readers would take note of his family’s poverty as discussed in his writing, Orwell chose to mask his identity; his new name stuck.

Orwell’s life experiences crystallized the uncompromising political views that are so strongly elicited in his works. Raised by a lower-middle class family in Motihari, India, he grasped the effects of wealth inequality from the get-go. Orwell’s early introduction to both writing and social injustices led him to develop his earliest literary work — a poem — at the mere age of four.

Seven years later, Orwell published his first piece in a local newspaper. Entitled ‘Awake! Young Men of England,’ the poem encouraged fellow Englishmen to enlist in World War I. Eleven years old at the time, Orwell could not enlist despite his early political enthusiasm, and thus settled on emboldening others.

This success was not the formal start of his career as an author. Rather, he finished school on a half scholarship at St. Cyprian’s School, and later, at two prestigious English universities, Wellington and Eton Colleges.

Even within his scholastic endeavors, Orwell noticed that the way in which students were treated depended heavily upon their class. Wealthier pupils received more academic opportunities than their less privileged counterparts; thus, his fierce opposition to class inequalities was born.

Following his graduation, the author became desperate for a source of steady income. As a result, he joined the India Imperial Police Force in 1922 and stayed for five years. This introduction to the professional world presented an inside look into the system of which Orwell would produce a scathing opprobrium (titled ‘1984’) just twenty seven years later.

Earlier, however, came the publication of his first novel in 1933: ‘Down and Out in Paris and London.’ The novel’s central theme is poverty within the two cities, harping on the lives of the working class. Orwell’s firsthand experiences as a dishwasher, for example, allowed for his writing to maintain a genuine tone when discussing the struggles of the lower class.

(Sela Emery)

Carson Michel ’23 concurs with a myriad of Orwell’s anti-capitalist criticisms, claiming that “capitalism’s emphasis on the rich extracting profit from the labor of workers in exchange for meager wages” creates a “cycle of poverty.”

His next novel, entitled ‘Burmese Days,’ was printed just a year later in 1934. Inspired by the dark facets of British imperialism in India, the novel’s plot can be credited for sparking Orwell’s passion for politics. “Englishmen,” explained the narrator on page twenty four of ‘Burmese Days,’ “should never be allowed to set foot in the East.”

A mere four years thereafter, he wrote ‘Homage to Catalonia.’ The 1938 novel was a tribute to his time in Spain, where he fought in the Spanish Civil War. His presence in the Republican militia was driven by his disapproval of the facist government, indicative of Orwell’s willingness to go to any lengths in order to defend his potent political views.

Soon, he began to work for the BBC, propagating socialist ideals under the weekly magazine “Tribune.” From 1941 to 1943, he endured long work hours, which he described as “something between a girls’ school and a lunatic asylum.” He found the job to be “slightly worse than useless.”

Following the resolution of World War II in 1945, Orwell produced one of his best known works: ‘Animal Farm.’ The novel is set on Manor Farm, whose proprietor has been violently driven out in a rebellion by his own livestock. The animals are left to govern themselves using their miraculously sophisticated understanding of politics.

Three pigs — Napoleon, Snowball, and Squealer — take the reins on commanding their peers. Their inability to follow their own rules, however, catalyzed chaos.

The hogs attempted to counterbalance their misdoings by governing with a dictatorial, iron fist, rendering the governing state, or lack thereof, one of near anarchy.

The novel ends with a shared dinner between pigs and humans on Manor Farm, with the other animals remarking at their inability to tell the two species apart. Orwell conveys that humans demonstrate “piggish” behavior, chiefly Soviet political leaders.

‘Animal Farm’ is a harsh critique of Soviet communism, with every detail down to individual characters paralleling twentieth century Russia. Napoleon, Snowball, and Squealer, for instance, are symbolic of Joseph Stalin, political theorist Leon Trotsky, and propagandist Vyacheslav Molotov respectively.

Thus, Orwell’s writing calls into question which revolutions occur for the greater good of the people and which occur to fulfill personal agendas. ‘Animal Farm’ argues that the Soviet Union falls under the latter category, abandoning any sense of humanity. Orwell’s disapproval was strong; he originally supported World War II — in which the Soviet Union played a pivotal role — because he saw it as an opportunity to instill a sense of socialist purpose within international governments.

His criticisms were extreme; the publication of ‘Animal Farm’ was delayed by a Russian spy working for the Ministry of Information, fearing its singlehanded threat to the Soviet government.

Naomi Kleinberg, an editor at Random House, classifies the novel “in the ‘if the Nazis had won’ arena.” She compares it to “The Plot Against America’ by Philip Roth,” “The Book Thief’ by Markus Zusak,” and “Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury.”

(Sela Emery)

Though she writes for young audiences, Kleinberg’s experience in editing adult novels is a valuable look into the recurrences of themes in the literary world.

Such themes appear in Orwell’s most famous piece, ‘1984.’ Kleinberg describes the novel’s parallels to the modern day as “odd — and scary,” despite its publication many decades ago in 1949.

Subject to the omnipresent, harsh laws imposed by “Big Brother,” Winston, the protagonist of ‘1984,’ falls victim to the totalitarian government. He is arrested and tortured for the heinous crime that is thinking “Big Brother” to be less than perfect. On a mission to manipulate the minds of citizens, the authorities feed Winston misinformation. Through painful methods, they engrain falsities into his mind; he leaves the prison believing that two and two make five, for instance.

The use of fake news, propaganda, and surveillance are highlighted in ‘1984.’ Though these themes are more blatantly illustrated in his writing, Orwell alludes to the fact that modern day American politics contain traces of the same deficiencies. He argues that citizens are all pawns in the government’s malicious game of chess, undermining the “unalienable rights” that citizens were promised centuries ago.

“From power dynamics to privacy rights, civic responsibility to cancel culture, Orwell’s echoes grow louder with each passing year,” said Bronx Science English teacher Mr. Daniel O’Brien. Sophomores enter his classroom eager to read ‘1984,’ leaving with a deeper understanding of the flaws in the world around them.

‘1984’ begins with a call to the ticking of time: “It was a bright day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” The novel’s critiques of society’s long-standing social fabric, however, are time-less.

“From power dynamics to privacy rights, civic responsibility to cancel culture, Orwell’s echoes grow louder with each passing year,” said Bronx Science English teacher Mr. Daniel O’Brien.

Sela Emery is a Copy Chief for 'The Science Survey.' She focuses on art history, covering relevant art pieces and exhibitions with each issue. In addition...