The Life and Times of Franz Kafka

The story of one of history’s greatest writers, and why his work is more relevant today than ever before.

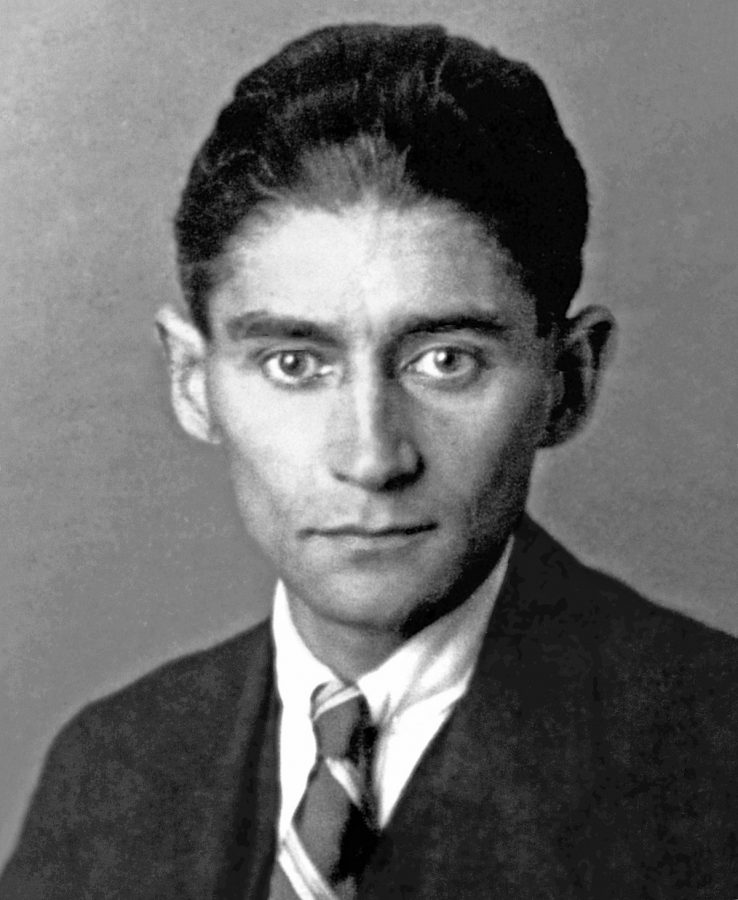

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A portrait of Franz Kafka, taken in 1923 by an unknown photographer.

“Genius is never understood in its own time.” is perhaps the most famous quote from Bill Watterson’s legendary comic strip Calvin and Hobbes. Despite its origins in a comedic medium, the quote managed to enter the zeitgeist as a sourceless fact. It is simply true.

The quote maintains this status on the backs of a few notable individuals whose work rose to prominence after their deaths. Vincent Van Gogh only sold one work of art in his lifetime, but over a century later, he is considered to be one of the greatest painters of all time. Edgar Allen Poe died penniless in the streets, but his enduring works are now credited with pioneering the horror genre.

Obviously, a few examples do not constitute a universal truth, but they do manifest a pattern about certain artists simply living and working during time periods that, for various reasons, were not properly equipped to appreciate them.

Enter Franz Kafka. Born in 1883 in Prague, Kafka lived an unassuming life working as an insurance clerk while trying to get his writing published. He published a few of his now-famous stories during his lifetime before dying of tuberculosis in 1924 at the young age of 40.

After his death, he requested that his friend (and later biographer) Max Brod destroy all of his unpublished and unfinished works. Instead of listening to his late friend’s wishes, Brod published Kafka’s writings, catapulting his friend into the spotlight, and helping him become regarded as one of the greatest writers of the century by the 1960s.

But Kafka was not done yet. His works continued to gain popularity, inspiring the creation of a word to describe the unique subject matter of some of his more influential stories. The first known use of the word Kafkaesque was in 1939, and it describes works that adhere to Kafka’s themes of isolation within modern society, often focusing on the chaos of bureaucratic systems and the people that operate them. His most enduring stories, The Metamorphosis and The Trial, are required reading for high school students worldwide.

But what prompted Kafka to write the way he did? Well, the aspect of his life most people point to is his time as an insurance clerk for two separate insurance companies. And while these jobs were undoubtedly major influences on Kafka (especially for The Trial) many, including Max Brod in his biography of Kafka, point to the author’s family life as the true driving force behind the themes on which he wrote.

Kafka had a difficult relationship with his father, and much of his life he spent torn between chasing his dreams and making his father proud. Hermann Kafka was, by all accounts, emotionally abusive to his only son, whom he saw as full of (in Kafka’s words) “coldness, estrangement and ingratitude.”

Kafka took after his mother’s more soft-spoken, anxious and inward-looking side of the family rather than emulating his gregarious hot-tempered father. This, as well as Kafka’s lack of siblings his age, led to him feeling like an outsider in his own family. He outlines these feelings in a 50 page letter to his father that he wrote, which he never delivered.

Max Brod writes about their relationship throughout his biography of Kafka, saying that “Of all the impressions of Kafka’s childhood the one that is of outstanding importance is the grand image of his father – exaggerated in its grandeur as it undoubtedly is by Kafka’s natural genius.”

And so, Kafka began writing, and with his difficult relationship with his father haunting him all the way, it is rather unsurprising that he wrote about the subjects he did. Kafka felt alone in his own family, and in a large city during a time in history where humans were becoming increasingly interconnected. Suddenly ‘Kafkaesque’ starts having less to do with an indictment of modern bureaucratic life and more to do with isolation against the odds.

In The Metamorphosis, a young salesman finds himself mysteriously transformed into a giant insect. This unfortunate development leads to him being alienated in his own house, despite his family’s proximity. In The Trial, a man is arrested for an unexplained crime and makes his way through an inane bureaucratic system in which he feels alone, isolated and helpless. These are Kafka’s two most famous works (the first a short story and the second a novel), and they very clearly mirror Kafka’s feelings of everyday isolation, and the effects of such loneliness on the psyche.

It makes sense that Kafka did not truly gain recognition until decades after his death. After all, he wrote during a time when most people did not feel the isolation that he felt. He was writing to express his feelings about his father, but not everyone in Kafka’s time had an abusive father, or worked in an insurance office. People did not feel lonely in spite of their connections, but rather connected despite their isolation.

But today, in the age of the internet, and social media, we are technically more connected than ever, yet studies show that depression and loneliness are on the rise. It may be that the one upside to the current mental health crisis that the world faces is that we are now positioned to view Kafka’s work as he viewed it, as an examination of what it truly feels like to be lonely in a crowd.

It may be that the one upside to the current mental health crisis that the world faces is that we are now positioned to view Kafka’s work as he viewed it, as an examination of what it truly feels like to be lonely in a crowd.

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...