So You Want to Be a Comedian? A Profile of Nikki Palumbo

Queer non-binary comedian Nikki Palumbo talks about how her identity and experiences have shaped her as a performer, writer, and person. Her work has appeared in ‘The New Yorker,’ ‘McSweeny’s,’ and ‘Reductress.’

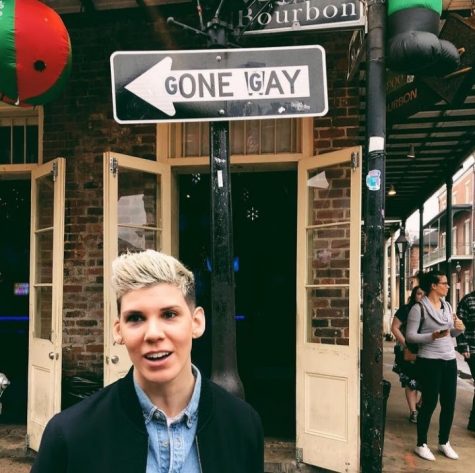

A post of Nikki Palumbo on Instagram — an app that she uses to post career milestones and the ups and downs of her life. “One of my New Year’s resolutions was to live more authentically, to share things, and feel more aligned with the people in my life, so I have been trying to use a less polished version of Instagram. I’ve posted about a mental breakdown last year or bouts of depression and those, ironically, are the posts that get the most engagement — that’s the human aspect that’s usually missing from social media,” Palumbo explained.

It all started back in eighth grade social studies class, when the students were slugging through vocabulary practice.

The teacher called on Nikki Palumbo, asking about the word ‘emigrate.’ Palumbo saw her chance and took it: “Am-I-great or what?” she had asked, prompting laughter from all the girls and consequently unlocking a new feeling of affirmation and satisfaction.

“I think that was — not the driving force — but that was the sharpest memory of, ‘Oh! If you make people laugh, they pay attention to you.’ And sometimes you can focus where you want your attention from.”

When asked about why she chose to become a comedian, her short answer was that she probably did not get enough emotional validation as a child. But in all seriousness, she has always been drawn to trying to understand people and herself which, according to her, is a lifelong adventure that never ends.

“You’re somehow never done learning about yourself. Can you believe it? And so, yeah, as a comedian a lot of what I do is trying to understand myself and how I relate to other people, and how I often can see patterns in the world just from living my life, and that is beautiful ammunition for writing and performing comedy. So, why be a comedian? It’s like, why not? Why not try to connect to people? In ways that entertain them and only hurt me a little bit!”

Like dance and poetry, comedy is also another art form often used as a light-hearted way to talk about problems in the world. Every comedian weaves in a part of themselves and their identity through their jokes in such a way that not only amuses the audience, but also raises awareness and interest about specific topics.

How does comedy tie into your identity as a queer non-binary individual?

“A lot, it turns out. I think part of the reason I was drawn to comedy in the first place was because I was raised in a very conservative Italian-American home. I make the joke that I came out to my parents as queer and they came out to me as Republican and I’m like, ‘Well okay only one is a choice!’ And then they sent me to Catholic school for 10 years and all of that was really transformative time and experiences, and I think because I was really uncomfortable in a lot of those environments as myself, the way to make myself comfortable was to find an outlet and to find a coping mechanism. And there’s nothing more beautifully defensive than making the joke first.

Again, a lot of comedy is connection and sharing stories, and it’s been years of meeting people who have very similar experiences, or they’re close enough to figure out what the universal truths are — we’re all just doing the best we can on this big floating rock that may or may not be a simulation, so how do we understand each other? So it’s just trying to take my experiences as a queer person, trying to live my life, and connecting it to people who may not even share these experiences. Like, ‘Hey, let’s just try to understand each other a little bit better, we’re not that different.’ I would argue that we’re not different at all.”

The name Palumbo translates to “peace pigeon” in Italian — a part of her identity she often showcases on her Instagram by posting pictures of her family and their sausage parties.

Are there any specific experiences surrounding your sexuality and your family that you tie into comedy?

“Obviously when you’re growing up, whether you’re told something explicitly or not, you can kind of read the room and I think that’s a skill that makes me incredible at comedy. It’s like, Oh I can tell how people are feeling, just by walking into a room and sometimes it’s like, ‘I’m gonna go, the energy in here is bad.’ My parents only know what they know, which is both frustrating and a relief sometimes to be like, ‘I don’t know what I’m expecting here— you’re trying your best and that’s going to have to be okay.’ So I didn’t have too many early experiences where they weren’t supportive, but it was a really big ramp up to finally come out to them, because I wasn’t 100% sure how that would go.

And it ended up going, as far as coming out stories go, as good as I could’ve hoped on that spectrum. I didn’t formally sit them down and come out to them until I was in my mid 20s, and I did it in a panic, so I wrote a whole essay about it — yeah ,there’s nothing quite like coming out to your parents, because your sister brings home the dumbest man you’ve ever met in your life, and you’re like, ‘Oh this is allowed in the house?’ So if this is acceptable then I can bring home a dog — I would love a dog. It’s just that I’m making this a bigger deal than I think they will make. Wow that answer really went off the rails!

But yeah, I’ve taken all of those experiences and tried to find ways to play with it, process it. A huge part of making comedy out of anything – even a little difficult – is to try to understand why that happened or how I feel about it. So I find that dealing with my more conservative upbringing is actually incredibly useful for making comedy.”

Palumbo stands at 5’9”, has short cropped hair, wears a lot of flannels and has bad posture — all of which are key factors in determining if one will be called “sir” or “ma’am” in public. Palumbo has been mis-gendered so many times in public that she wrote an entire article about it on the McSweeney’s website titled “AN OPEN LETTER TO PEOPLE WHO CALL ME “SIR”.

In the beginning of the article, she writes about turning her experiences of being mis-gendered into a joke about the level of respect between phrases like “hey man” versus “excuse me, sir.” The piece then takes a more serious turn to the gender power disparity and privilege in our society.

How does one take something as serious and as uncomfortable as being mis-gendered and weave in sarcasm and comedy through it? And more importantly, how long does it take to really dig through yourself, your emotions, your fears, and be so vulnerable as to lay it into a very structured piece of writing?

“I didn’t realize I had comedy to make of this experience until I couldn’t stop talking about it. And then it was a little bit like, ‘Okay she talked about this too much, there’s something there. What is this triggering in me?’ It started as a stand-up bit — I get mis-gendered kind of where you’d expect. Where people barely look at your face so it’s very easy to make a judgement. Or like, ‘Okay, here are the three pieces of information I need: hair length, clothes, bad posture. And then it’s like, oh, that’s a man.’

No. I wish. Then I’d be in the other bathroom line.

And then the more I was performing it, the more I realized there might be a version of this that I can write that has a slightly different thread through it which was more of this privilege and power displacement – when I’m called sir, it’s almost like someone else has lost his power. It feels disruptive to a hierarchy, in a way. That’s what the written piece found.

As I started doing stand-up, I was like, ‘Oh, if you’re doing to be perceived in the world, your hope is that it’s how you perceive yourself,’ and there is something so jarring to me, even now, I mean I identity as non-binary, when someone calls me sir or uses he/him pronouns. I have a joke now where it’s like, ‘I use they/them pronoun sometimes because most days I do identify as a woman, but there are other days where I just kind of feel like a cloud— that’s a real nice in between.’

It’s just kind of like an internal thermometer of, ‘Am I ready to talk about this in a funny way at all?’ And then the humor comes from ‘comedy is tragedy plus time,’ so, ‘Oh no, somebody tried to address me respectfully, but they guessed wrong!’

I guess the real tragedy was the time where my actual doctor did it and I’m like, ‘I’m going to need you to go back to school for a little bit longer. I need you to learn how to read a chart.’ But yeah, the comedy comes from having a little bit of time with anything, and it’s easier to see it as an outsider, and you have a little bit more distance from it.

‘Alright, if I watched this happen, how would I describe this? What do I think the funniest parts are?’ So there’s a little bit of separation and dissociation to process it as both a lived experience, put that away, and then find the comedy nugget and look at it more as a piece on the page. It’s always hard to tell where life ends and art starts and where the art has ended and life starts again – it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

One of the best ways to deal with a problem or uncomfortable situation is to let it age and take your time internalizing and familiarizing yourself with it. Because comedians like Palumbo try to understand themselves first and take the initiative to talk about their problems in such an easy-going and comfortable way, they also hold a certain level of power and influence over the audience.

But after internalization, is there a specific process you go through when trying to make up something funny?

“It does seem like everybody has their own system, and I’m sure there are many different ways to do comedy – there has to be, it’s very subjective. I don’t write stand-up everyday, I write a bunch of different things. I’m never writing specifically one-off jokes or always trying to work on a comedy set. But my process, generally, is cataloging moments in my life or things that I care about. Things that make you feel something – there’s no wrong emotion to follow. Apathy is usually the best comedy – if you don’t care about it, then how is the audience going to talk about it?

The easiest way to set myself up for success when I’m writing is always having a note on my phone or notebook – that way I can keep track of even tiny ideas. So when it’s time to sit down and do the writing, I have some place to start from. If there’s a better system, I would love to hear about it, but it seems like everybody has their own process. I try to write something every day, but often what I’ve written is a to-do list where the first item is ‘write a to-do list’ so I have something to cross off. The shortest answer is: No, I don’t have a process.”

Palumbo also acknowledges how privileged she has been in her journey thus far as a queer non-binary individual working in a field dominated by straight-cis white men. She had the financial capability to take comedy classes at a comedy theater and kept following the ladder set by white men.

“I wonder if there’s somebody being like, ‘Oh no, I gave her an opportunity? I thought that was a dude!’ And then I’m like, ‘Ha, I snuck in!’ And now I’m going to kick the door open for people who should be sharing their stories. I tried following this path set by men and it just happened to work out. And a friend of mine was like, ‘Oh, there’s no queer sketch comedy at the theater, so why don’t we do that?’ So we had an LGBTQ sketch comedy show that ran in the theater that was the first of its kind. And that felt crazy to say in 2019. It’s like, ‘Wait, just now this is starting?’ Again, I’m sure there were way more doors closed for me than I thought, but I pushed my way through the ones that were open. My true mission in life is that the second I get my foot in the door, I’m ripping it off the hinges, so whoever wants to come in can come in.”

Palumbo did not have many non-binary or female comedians to look up to when she was younger. She mentioned that during her youth, Ellen DeGeneres was the most popular lesbian comedian on TV and praised DeGeneres’ writing. People do not typically picture written words when they think about comedy. Instead, they picture something more spontaneous like making people laugh in a conversation, whereas writing is very deliberate.

What is the difference between a writer and a performer, and how do you find the balance between spontaneity and deliberation?

“It feels like a little bit of a brain vacation when you’re just trying to connect with your friends and you happen to say something funny. Often my written pieces start in conversation, so it’s very easy to say something off the cuff and then kind of see a visual of it and how there’s actually something more to that than how it contributed to this conversation. And yeah, there is a very deliberate process of like, ‘Okay, how does this live on the page?’ Most of my stand-ups are written, and the trick is to rehearse it well enough that you think I’m coming up with it every time I do it.

There’s something really satisfying about saying something funny in conversation because it’s confirmation that your brain is working. And then there is that instant gratification of a response. But with writing, it’s a much lonelier journey, because it’s just me with my ideas. I can’t remember the last time I wrote something that didn’t go through nine drafts; the writing process is just getting comfortable with the rewriting. With every draft of something, it’s easier to find another layer of the humor or something that feels truer.

I just submitted a new piece to The New Yorker that is actually a resubmission of something that I wrote last year that was something that they liked, but they were inundated with pieces about the same topic. So I reread the piece two weeks ago and punched up a couple jokes, and so it was nice to have sat on this for a year, and then to resubmit it and find out.

They do feel like two very different skills but maybe they’re not. They’re just separate processes.”

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this year has been incredibly different as everything, including comedy, has gone virtual. Palumbo often posts one-liners on her Twitter and Instagram account but has recently had a recalibration of how she uses social media.

For a while, Twitter was her go-to place for comedy jobs. However since she feels that Twitter has become an incredibly toxic space, Palumbo simply uses the app as a rough draft folder or a scratchpad of ideas that she eventually tries to perform on TikTok. Instagram is reserved for career milestones but she dislikes how extremely filtered and polished the app appears. Another app that has risen in popularity since the start of the pandemic is Zoom — the online video conferencing app. Palumbo, however, is not a big fan.

“Yeah, I’ve done a few shows because it’s so bizarre to me. It feels so jarring to me to perform to a computer and not have any part of the human experience and that feels like an essential component to stand up comedy. I did maybe three or four shows and I was like, ‘You know what? I’ll just wait.’ I’ll focus on other kinds of comedy. I will just wait until it feels safe to do this again in person. It feels really dystopian, it feels like an episode of Black Mirror. There’s a version of reality where you never perform to a live audience again or you don’t get a live audience reaction. And in that case, I would stop doing comedy that way because that’s not good enough.”

Not only does Palumbo write for large media establishments like The New Yorker, McSweeny’s, and MTV, she also mentors at Girls Write Now — a non-profit organization that provides writing opportunities and help for under-served girls and gender-diverse youth. Girls Write Now brings in many influential professionals in various fields to help their mentees. Palumbo started working there about six years ago.

“I was writing comedy at the comedy theater and got an e-mail from the artistic director who said there’s this organization, Girls Write Now, who are doing a sketch comedy writing workshop and they need additional mentors to guide through the workshop. So I volunteered and spent a lovely afternoon in the Girls Write Now offices helping girls write comedy. After the workshop was over, I asked the program director how I can do this more. She told me to apply to be a mentor. So I did and spent three years with my first mentee and two years with my second mentee. Not only have I worked as a mentor, but I work on the Anthology committee, and that has been very lovely.

My first mentee loved sci-fi and social commentary essay writing, so we worked on a lot of that. There was never a session where she didn’t blow my face off with something. Like, ‘How are you writing this? Where is this coming from? We need to get this published!’ She’s in college now, probably blowing somebody else’s face off. My second mentee loved writing memoir pieces. My experience with GWN has always been bafflement with how clear voices can be because that was not my experience when I was in high school so it’s been truly a joy to watch the talent skyrocket through the program. Again, ‘How?!’ At 17 I was downloading TV shows I shouldn’t be watching!”

Do you write works besides comedy?

“Yeah, I started writing poetry. I went through a really bad breakup, and poetry was the first thing I turned to. And it’s funny poetry. It’s hard to remove that part of how I write, so there’s a little bit of humor in all of it — I hope nobody ever reads it. Watch, someone will trick me into publishing it. And I realized I have a bunch of beautiful stationery and stamps — because I guess I’m trying to save the post office by myself — so I put out a call on Instagram asking if anybody wanted a poem or a letter. A bunch of people said yes. I’ve also been writing TV pilots which are also comedies but a much longer form. It’s nice to explore all genres, because there’s so much to learn from all of them.”

Although Palumbo has not worked on any of her actual projects for a month because of her job, she has many plans for future projects and is excited to dive in. She recently wrapped up an MTV writing and awards gig which was, according to her, “stupid fun” and is looking forward to putting together a game show podcast with her friend. She is always trying to branch out and not just write for print.

Her final piece of advice to share with any woman, non-binary, and LGBTQ+ individual who wants to pursue comedy but is hesitant to set their foot out there was to:

“Think about everything in the world that is just fine and know that you will be better than that eventually. There’s so many just fine things in the world, and I feel like all of my favorite great things are usually from women. The only thing that often feels like it is holding you back is you because your expectations are so high. And that’s what’s going to make the thing so great, because you hold yourself to a much higher bar. So just do it. Let it be okay that it’s not amazing right away. It will be. It’s just a matter of time. Your story is worth sharing. Your perspective is worth sharing. I want to hear it for sure. So just do it.”

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. To listen to my audio interview with Nikki Palumbo in its entirety, click HERE.

“The only thing that often feels like it is holding you back is you because your expectations are so high. And that’s what’s going to make the thing so great because you hold yourself to a much higher bar. So just do it. Let it be okay that it’s not amazing right away. It will be. It’s just a matter of time,” said Nikki Palumbo.

Paromita Talukder is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey’ where she explores topics ranging from online activism to clubs at Bronx Science. She sees...