MEN! The kendōka yells, as a loud crack echoes through the room. A point has been given to the kendōka, and the match continues.

‘Kendo’ or ‘the way of the sword,’ is a Japanese martial art that utilizes a bamboo sword called a shinai, and many protective gears called bōgu or “armor” (more formally known as kendōgu, or ‘kendo equipment’). It is a martial art that demands a lot of concentration and respect for others as well as for oneself.

The term ‘kendo’ is a relatively new word that was first used during the Taisho period (1912–1926). However, the history of kendo is much older. Since kendo means ‘the way of the sword,’ its history is also deeply intertwined with the history of Japanese swordsmanship.

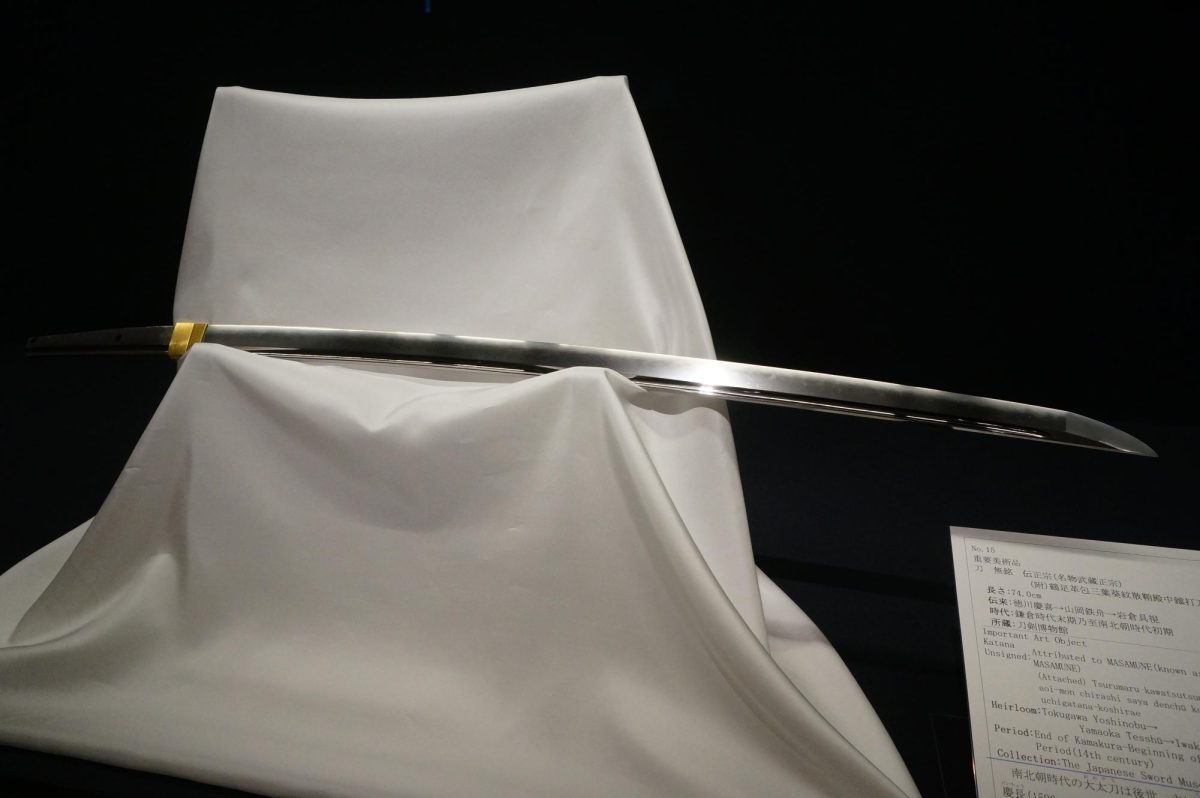

The first emergence of the shinogi, a sword with a curved blade and raised edge, was during the mid-Heian period (794-1185). With many warrior factions adopting the sword, production especially advanced toward the end of the Kamakura period (1185-1333). In parallel to these advancements in the sword’s production, was the art of swordsmanship.

With the Muromachi period (1336–1573) came the adoption of the the uchi-gatana, known for its upward-facing cutting edge and worn at the side, in many swordsmanship schools, like the Shinkage-ryū (new-shadow school) and the Ittō-ryū (one-sword school).

The founder of Shinkage-ryū , Kamiizumi Ise-no-Kami Fujiwara-no-Hidetsuna, developed a practice sword called the hikihada-shinai, made by splitting the end of a bamboo stick two to sixteen times and covering it in lacquered leather.

At the Ittō-ryū, Itō Ittōsai Kagehisa’s first successor, Ono Jiroemon Tadaaki created his style of Ittō-ryū called the Ono-ha Ittō-ryū. Ono-ha Ittō-ryū is a dueling style, thus Ono Jiroemon Tadaaki developed a mock split-bamboo sword called a fukuro-shinai.

The meaning of the sword and the nature of swordsmanship changed during the long period of peace seen during the Edo period (1603-1868). Swordsmanship was no longer about killing the other opponent, but instead took on a deeper meaning.

“Katsujinken” is a discipline that focuses on personal development and character building. This period was marked by fervent discourse on both the technical and psychological aspects of swordsmanship, exploring its deeper applications in life.

The early Edo period witnessed the creation of several influential texts that significantly shaped the art of swordsmanship. Among these was the “Heiho Kadensho” (1632), written by Yagyu Munenori, who served as a swordsmanship instructor to the third shogun, Iemitsu. Another notable work was Fudochi Shinmyoroku (1645) by Takuan Soho, a text delving into the intricate relationship between the sword and Zen philosophy, reflecting Soho’s interactions with Munenori. Additionally, Miyamoto Musashi’s Gorin no Sho stands as a significant contribution in the genre.

In the Shotoku era (1711-1715), Naganuma Shirozaemon Kunisato of the Jikishin Kage-ryu school popularized the uchikomi keiko-ho method of practice, in which adepts struck each other with bamboo swords (shinai) while wearing protective equipment

During the Horeki era (1751-1764), Nakanishi Chuzo Tsugutake of the Itto-ryu adopted and improved the uchikomi practice method by wearing an iron mask (men) and bamboo sparring armor.

This quickly spread to many other schools, and during the Kansei era (1789-1801), matches between different schools of swordsmanship became popular as swordsmen traveled the countryside seeking out strong opponents to test their skills against.

With the development of new techniques and training styles, many of the old equipment were also revamped. In the late-Edo period, the yotsu-wari shinai (made from four slats of bamboo) was invented, which was more durable than the hitherto popular fukuro shinai (bamboo wrapped in leather). Also, the do (torso protector) made of tanned leather and hardened with lacquer was developed.

With the development of the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912) the newly established government abolished the samurai class and prohibited the wearing of swords. It wasn’t until the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877 that the relevance of martial arts was recognized. The Dai-Ippon Butokukai was founded 1895 and was aimed to preserve and promote martial arts.

The term ‘kendo’ was first used in the Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kendo Kata (Greater Japan Imperial Kendo Kata) in 1912, which was later renamed Nihon Kendo Kata. The objective of the kata was to teach the future generations about the nihonto (Japanese swords) and how to wield them, as well as address the issues like the improper use of the shinai and the tendency to strike without considering the cutting angle.

With the post war period (1945~) after World War II and the Allied Powers’ occupation of Japan, kendo was banned. With the restoration of Japan’s Sovereignty in 1952 the All Japan Kendo Federation was established, signaling the rebirth of kendo. It was reintroduced not just as a martial art, but also as a component of physical education and a sport.

Kendo today is a significant component of physical education in Japanese schools and has gained popularity among people of all ages and genders.Its international appeal is apparent and has a vast amount of fans worldwide.

Kendo being a sport about self control requires a lot of discipline and respect for the self as well as for the opponent. Thus at the start of the round, you bow to your opponent by crouching at the start lines.

To score a point, you must cleanly hit one of the four possible striking areas: the men or head of your opponent, the kote or the gloves or wrist, the do or the torso, and tsuki a thrust to the opponents throat.

If you manage to successfully strike any of the four areas mentioned, then you score one Ippon or one point. Kendo is contested in one period of 10 minutes and is the best of three. Scoring two Ippon wins the match or being 1-0 up after the 10 minutes are up.

However, the requirements for an Ippon to be awarded are quite rigorous. The phrase Ki Ken Tai or Spirit, Sword & Body is the perfect summary of these requirements.

With Ki (or fighting spirit) you must shout with every attack, also known as a kiai and is required for an ippon to be scored.

Ken (or sword) is awarded when a string at the back end of the shinai is facing perpendicular to the striked area indicating that you cut your opponent. You must also strike at a correct part of the sword (25 cm from the tip of the shinai) and the attack cannot be too deep or too shallow.

The Tai (or body) determines whether or not you have a straight body position as well as having two hands on the sword when attacking.

The Final is Zanshin (physical and mental alertness). During the entire 10 minute match, you must be alert and concentrated, ready to strike at any time. A break in concentration may result in a point not being awarded or invalidated. For example, acts of celebration like making a fist pump may be considered rude or disrespectful and could cancel your ippon.

Every kendo fighter, or kendōka, is often tagged with either a red or white on their back. Three referees will hold the corresponding flags, and at least two judges have to agree before an Ippon is scored.

In kendo, if the scores are 0-0 or 1-1 after 10 minutes, it is considered a tie. In tournaments, the contest will carry on until an ippon is scored and whoever scores first wins. It could also be considered a tie, or the win will go to the person the referee’s deem to be the better swordsman.

So how is kendo different from iaidō and kenjutsu? All three martial arts are related, as they utilize the sword and swordsmanship as their main teachings.

Iaidō or abbreviated as iai, is a martial art that emphasizes awareness of your surroundings and the ability to quickly draw the sword and respond to sudden attacks.

There are four main aspects of iaidō. The smooth, controlled motion of unsheathing the blade, striking the opponent, shaking blood off the blade, and re-sheathing the blade.

‘Kenjutsu’ is a term that encapsulates all types of swordsmanship in Japan. It was originally kenjutsu that led to modern kendo and alternate martial arts, like iaido. Kenjutsu doesn’t have a singular method or fighting style. As each different sword school has a different style and utilizes different methods.

When I asked Sebastian Ye ’25 about the purpose of kendo, he said, “the whole purpose of kendo is to cultivate the mind and body, accomplished by practicing ‘the way of the sword,’ which is what kendo directly translates as. The main aspect is to teach discipline and rigor, with a strong emphasis on manners and respect. You’re supposed to learn from elders and treat everyone with respect and humility, no matter the ranking.”

When I asked how he disciplines himself and if he recommends the sport, Ye said, “the discipline part is mostly just perseverance through training and pushing, even when you’re exhausted. And regarding the second question, I highly recommend kendo as a sport. Even if you practice it without considering it a serious sport and only as a hobby, nonetheless, it’s still a great way to let go of stress and to develop a stronger mind. It’s also a nice exercise.”

These comments fully encapsulates the concept of Ki Ken Tai mentioned previously as well as the growing popularity of the sport globally. The first World Kendo Championships, held at the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, Japan, highlighted its growing international presence. By September 2018, the 17th World Kendo Championships in Incheon, Korea, saw participation from athletes from 56 countries and regions, demonstrating kendo’s expansive reach. The 19th World Kendo Championships are set to be held in Milan, Italy, in July 2024, continuing the tradition of international competition.

‘Kendo’ or “the way of the sword” is a Japanese martial art that utilizes a bamboo sword called a shinai, and many protective gears called bōgu or “armor” (more formally known as kendōgu or ‘kendo equipment’). It is a martial art that demands a lot of concentration and respect for others as well as oneself.